Many classrooms across the globe have learners coming from different language backgrounds. In this article, Amy Lightfoot discusses multilingual approaches that teachers can use within the classroom set-up.

In India and many other countries around the world, multilingual classrooms are the norm. Developing an understanding of how to capitalise on learners’ home languages to support learning is fundamental to academic success – particularly when that learning is happening in a non-dominant language such as English.

Research undertaken in multilingual contexts such as India, South Africa, and Australia has shown that early instruction in a child’s mother tongue – especially for the first eight years of schooling – can have a considerable impact on learning outcomes across the curriculum. This is also true when these learners progress into higher education.

It is no surprise that learners learn best when taught in a language that they understand, nor that a strong foundation of literacy (ability to read) will be instrumental as the child progresses through school and uses reading to learn. Furthermore, the message that a learner’s language is less important because it isn’t featured as a medium of instruction within an education system can negatively impact his or her identity, and respect for his or her cultural roots.

In the long term, this can reduce language use to such a degree that it disappears from day-to-day life, to the detriment of a community’s rich cultural and linguistic diversity.

Case study: approaches used in English language teaching

Approaches used for English language teaching are an interesting case study when considering the perceived value and use of learners’ home languages within the learning process. Trends in this field of education have swung over time.

When the grammar-translation method was popularised in the 19th Century, extensive use of translation was recommended. Later, recognition of the need for greater exposure to the target language resulted in suggestions that teaching should be strictly monolingual in nature, with perhaps some concession made for absolute beginners.

More recently, the value of learners’ existing linguistic resources has been foregrounded. In English medium instruction environments in India, a recent study by this author and Jason Anderson in 2018 found that there are prevailing attitudes among teachers that both they and their learners should attempt to use English only, wherever possible.

Very few of the surveyed teachers reported purposeful use of the learners’ own languages to support learning. In fact, several of the teachers stated feelings of guilt when ‘resorting’ to home languages – believing that it was evidence of failing as a teacher. Many of the teachers felt under pressure to maximise English in the classroom (and therefore reduce home language use), either from the head teachers in their school or because of expectations from the students’ parents.

However, it’s not just teachers (or just teachers of English) who struggle with how best to integrate the use of learner languages in the classroom. Policy documentation around the world is frequently deficient regarding these issues.

A recent study by Santoro and Kennedy (2016) explored the professional standards for teachers published by five education systems in Australia, British Columbia (Canada), England, California, and New Zealand. They analysed the extent to which these standards referenced the need for an awareness of student cultural and linguistic diversity and how teachers can best address and exploit this in the classroom.

Their analysis found that while there is reference in all of the five sets of standards to the need to respect all learners and to be aware of their cultural and linguistic backgrounds, there is no explicit guidance or strategy for how this is to be done.

Continuing professional development

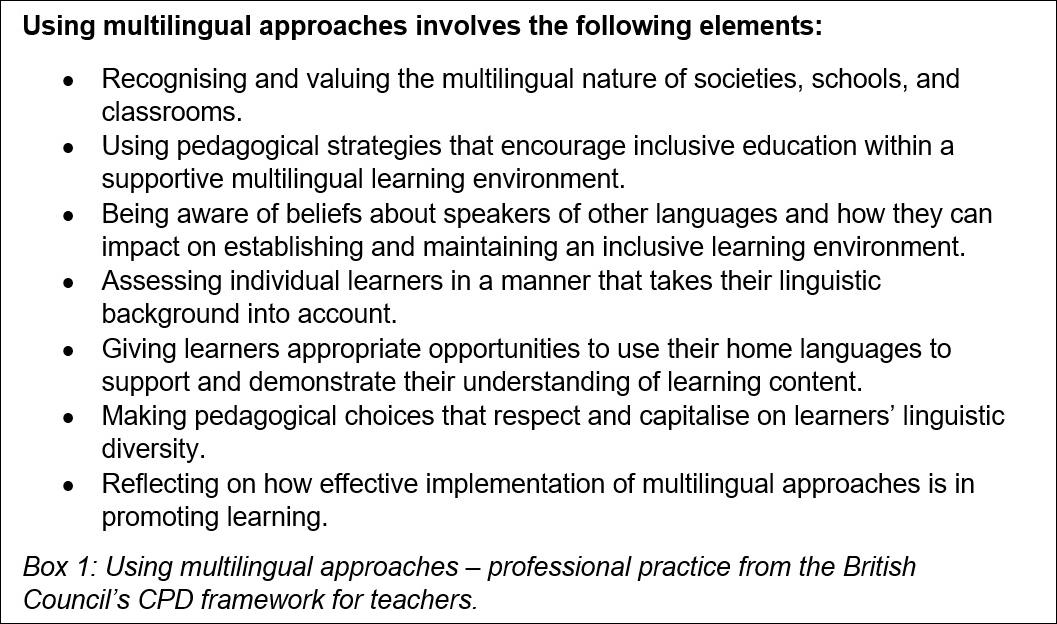

The British Council’s Framework of Continuing Professional Development for teachers contributes to reducing this gap through its inclusion of the professional practice ‘Using multilingual approaches’. Describing the development of teachers through the stages of awareness, understanding, engagement, and integration, the sub-elements that are articulated for this practice go some way to identifying specific strategies and ideas for teachers to adopt in their classrooms (see Box 1).

Nevertheless, resources to help support teachers use their learners’ existing language to effectively support their learning and understanding remain limited. So, what can teachers do? Below are some suggested ideas for how teachers can begin to engage with learners’ home languages in their classroom.

Classroom ideas for engaging with learners’ home languages

1) Find out about your learners’ use of language: interview your learners to find out what languages they use, for what purposes and when, or better yet, ask them to interview each other. Observe them during school break times – what languages do they use in the playground? Work with your class to create a language display for your classroom: Our class can speak all of these languages.

2) Think carefully about your own beliefs, and where they come from. Do you feel uncomfortable when learners speak in languages other than the main language of instruction? Why? Is it because you don’t understand, or something else?

3) Think about how you use language yourself; how many languages do you use on a regular basis? What do you use them for? How do you feel when you use them?

4) Consider whether you could get students with the same home language working together in groups sometimes. Could they support each other’s learning by discussing ideas in the language they are most comfortable in?

5) If most of your learners are learning in a language other than their mother tongue, consider whether you can ask them to do productive tasks first in their home language (individually, in pairs or in groups) and then (once they have worked out the questions of content or what they want to say), repeat the task in the target language. This way their effort in the mechanics of using the target language doesn’t get mixed up with the effort in deciding what to talk or write about in the first place.

A version of this article first appeared in the print magazine Teacher, distributed in India, in April 2019.

References

Anderson, J., & Lightfoot, A. (2018). Translingual practices in English classrooms in India: Current perceptions and future possibilities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(8), 1210-1231. DOI: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1548558

Santoro, N. & Kennedy, A. (2015). How is cultural diversity positioned in teacher professional standards? an international analysis. Asia- Pacific Journal of Teacher education, 44(3), 208-223.