Kavita Sanghvi shares findings from an action research project aimed at understanding how students responded to online assessments administered by their school during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Millions of school-going students across the world have been affected by the closures of educational institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many such institutions shifted to online learning in the past year with the help of virtual teaching-learning platforms.

Assessments play a crucial role in the teaching-learning process. A well-designed assessment instrument can provide insights into a student’s understanding of concepts, application, and skills. It helps teachers reflect on the curriculum design and execution and provides inputs for modifications and revisions. It also measures an institution’s academic progress and how well its students are learning.

Until March 2019, as teachers we could confidently say that we were familiar with effective student assessment methods administered in physical classrooms. However, the pandemic forced us to assess students online, often through unfamiliar means. Formative assessments included e-book/poster projects, presentations, quizzes, and online discussions and debates. Summative evaluations initially began with simple Google or MS Teams forms for objective evaluations with one camera monitoring students, and Exam.net or other media with two cameras for subjective assessments. However, the reality is that even after 10 months, we are still wondering if students have actually learnt what they were taught.

We would like to believe that learning experiences were well constructed by educators and students attempted all assessments honestly, but we cannot ignore foul play in certain instances. Moreover, as the transition was sudden, many teachers were not fully equipped to teach online and were consequently apprehensive, leaving learners to learn in isolation. Also, using different information technology platforms led to different levels of competencies and proficiences among students (for more information, read Little-Wiles & Naimi, 2011; Rucker & Downey, 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016; Thorsteinsson, 2013).

Educators and school leaders need to know if the learning curves of individual students have moved up or down as a result of online teaching and assessments, and understand how they can modify their assessment approach to improve the validity and reliability of online assessments. With board examinations arriving in a few months, the major challenge is for Grade 10 and 12 teachers who are preparing students for examinations that have significant meaning for them.

Action research project

An action research project was designed in my school to understand students’ perspectives on:

- the efficacy of school online assessments and their impact on learning

- students’ trust in e-assessment

- concerns and inputs for online assessment.

An online survey (Google form) was administered to 616 students in Grades 9−12 of a school. The first two questions of the questionnaire were two closed Likert scale questions. The third question was a simple yes/no question followed by six Likert scale questions and one yes/no question. The final question was an explanation for the last yes/ no question. A total of 11 questions were asked of students via the survey.

The findings of the project helped our teachers understand the strengths of the online assessment practices in our school and the areas that would require further improvements. It also helped them to reflect on specific problems of students and take action to change the situation.

Findings

- Students were asked whether they felt that their learning progress had been adequately measured through online assessments and only about 11 per cent strongly agreed. This is rather surprising given the advantages and flexibility inherent within an online learning environment including wide-ranging opportunities for conducting effective assessments through technological platforms (see Benson & Brack, 2010; Broadbent & Poon, 2015; Crawford-Ferre & Weist, 2012; Napier et al., 2011). This finding indicates that our teachers have to investigate in-depth why our students are dissatisfied with such assessments and work towards improving their assessment experience.

- When students were asked if their study space and movements were effectively monitored during invigilation, around 33 per cent strongly agreed. They felt that their teachers were highly vigilant and monitored student actions with great scrutiny.

- Teachers in our school began by assessing students with one camera and then started using two to ensure effective monitoring of movement. Students were asked if using two monitoring cameras instead of one was more effective during online assessments. Almost 61 per cent of them felt that using two cameras was more effective. This indicates that our teachers have made an appropriate move by switching to invigilating with two cameras.

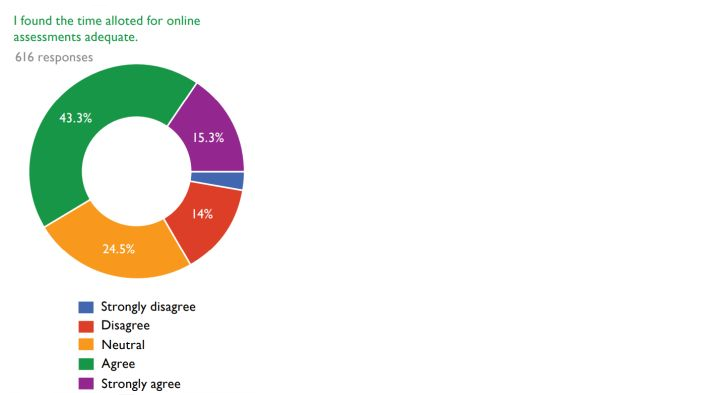

- Online assessments demand more time. Students have to download papers and upload their submissions and our teachers often have to stretch the assessment time limit from 15 to 30 minutes depending on a student’s internet status at home. When students were asked whether the time given to complete assessments was sufficient, only 15 per cent strongly agreed, which caused our teachers to reconsider the time given to students to upload assessments online

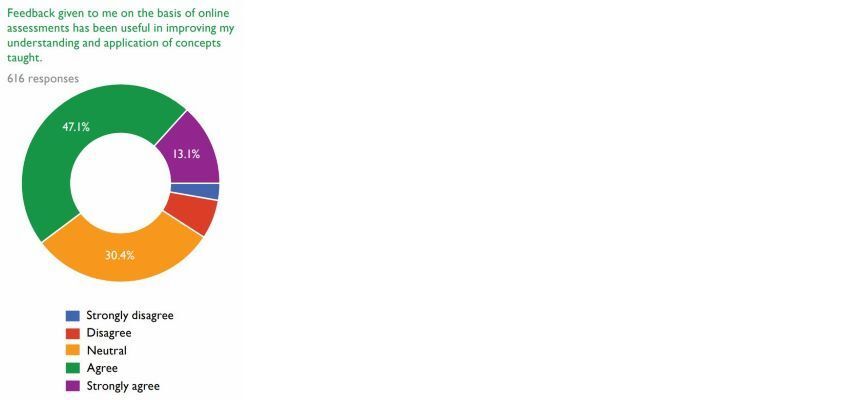

- Students were also asked if the assessment feedback given to them helped improve their understanding and application of concepts taught. Only 13 per cent of students strongly felt that feedback from teachers helped to address concept gaps. So, where did we go wrong? In face-to-face learning, a teacher can understand a student’s body language and gauge how well students have accepted any feedback and are ready to improve. This is not possible in an online learning environment. Thus, our teachers realised that they had to reconsider their method of evaluating student assignments and offer feedback that would be considered constructive by students.

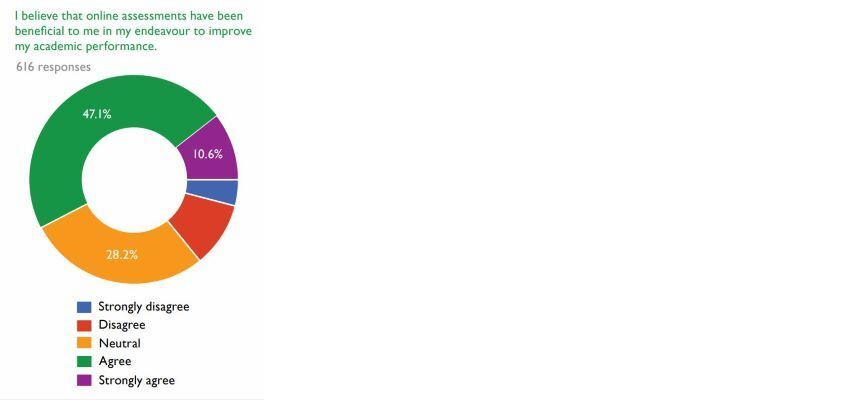

- Only 11 per cent of students felt that online assessments helped improve their academic performance. This result was a little surprising for our teachers – many students scored much more in online assessments than they usually do in paper and pen tests. However, the data raises concerns; our teachers have to plug large learning gaps when students return to physical classrooms. Moreover, teachers supplemented written exams with viva voce examinations that helped identify a significant difference in written and oral examination performance of students. Such variations also indicate that the area of online school assessment needs more work – an important learning for teachers and the management of our school.

- Around 25 per cent of students were unsure if online assessments measured and reflected their academic progress correctly.

- The investigation also sought to examine if online assessment leaves more scope for cheating. If 31 per cent of students agreed strongly and 36 per cent agreed, it indicates that our school should look into minimising the use of unfair means in online exams. Academic research has also highlighted this point – students often search for answers on other devices and social media, and seek help from friends during online assessments (see for instance, Owens, 2015 and Best & Shelley, 2018). However, Golden and Kohlbeck in 2020 found that proctoring technology can help prevent such distortions and this could be a solution in the future.

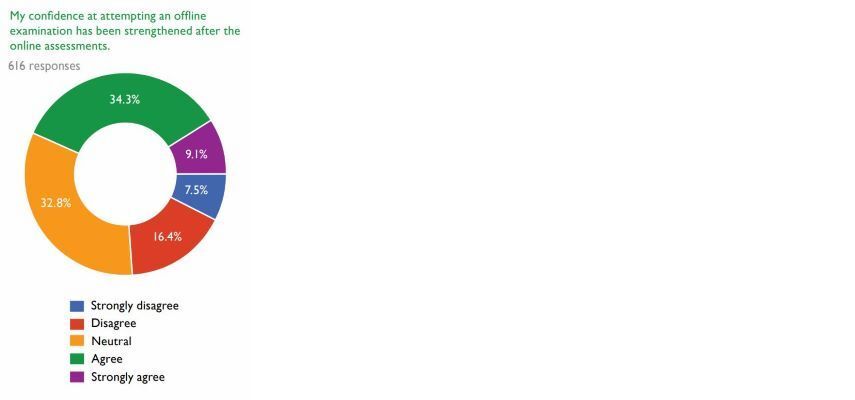

- With the Board exams around the corner, one wonders whether students are confident about appearing for offline exams. Only 9 per cent students showed confidence and that is again a worrisome figure.

- Around 45 per cent of students preferred online exams even though only around 13 per cent felt that online assessments reflect their academic progress. This is a conundrum for our teachers – why do students still prefer online assessments?

Conclusion

Students highlighted concerns such as ‘online assessments are hectic’, ‘it was difficult to create exam like atmosphere at home’, ‘too many distractions’, ‘online not close to real exam situation’, ‘lots of malpractices’, ‘network issues’, and ‘strain on the eyes’. They preferred paper and pen exams in which students comprehended questions better, felt more confident, and believed that physical tests measure their skills more proficiently.

On the other hand, online tests helped them feel safe and less worried about COVID-19 infections. They also believed that their teachers had supported them during these confusing times. Recording of paper discussions helped them work on their misunderstandings. The online environment offered better utilisation of time and effort, helped avoid exam phobia, and offered assessments in the comfort of their homes.

Students feel that online learning is only a temporary solution. Nevertheless, it has offered many advantages like going back to recordings of paper discussions and lessons till one is confident about a concept, different modes of assessment, less stressful environments, and better utilisation of space and time. Thus, teachers and the school management of our school will have to take into account all these points when students return to physical classrooms. Should we move to blended forms of teaching-learning and assessments?

A version of this article first appeared in the print magazine Teacher, distributed in India, in April 2021.

References

Dendir S., Maxwell R.S. (2020). Cheating in online courses: Evidence from online proctoring. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100033

Elzainy MD A., Sadik MD A.E, Abdulmonem A.W., (2020). Experience of e-learning and online assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic at the College of Medicine, Qassim University. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences 15 (6): 456-462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.09.005

Mehra A. (2021, January 13). At IITs, With Online Exams, Teachers Confront High-Tech Cheating. https://www.ndtv.com/opinion/at-iit-withonline-exams-teachers-confront-high-techcheating-2351311

Özden M.Y., Ertürk I., and Sanli R. (2004). Students’ perceptions of online assessment: A case study. Journal of Distance Education, 19 (2), 77-92.

Serpil K., Abdulkadir K., PeytchevaForsyth, K. & Stoeva, V. (2018). Cheating and plagiarism in e-assessment: Students’ perspectives. Open Praxis, 10 (3). https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.3.873

UNESCO. (2021, January 21). On International Day of Education, UNESCO promotes learning recovery for students affected by COVID-19. https://en.unesco.org/news/international-day-educationunesco-promotes-learning-recoverystudents-affected-covid-1