Teachers are constantly trying to improve their instructional practices to better support learners. In today’s reader submission, Ima Kazmi – secondary school English teacher and Curriculum Leader for English at The British School, New Delhi – shares how she has used worked examples in her classroom.

How many times as a teacher have you heard a fellow practitioner use the catchphrase ‘I do, we do, you do’ in conversations around effective teaching? Emerging as a pedagogical mantra, it is meant to capture the educational framework where we move from teacher modelling to scaffolded problem solving to independent problem solving. Whilst pithy slogans carry undeniable charm, what educational discourse has benefitted from is an elaboration of what exactly is meant by ‘I can do, we can do, and you can do.’

For any educator familiar with Barak Rosenshine’s ‘Principles of Instruction’ and Tom Sherrington’s (2019) commentary on it, a well-etched blueprint emerges on how teachers can help their students grasp abstract concepts and skills by providing cognitive support. Models and worked examples form a central piece of this, alongside a well-sequenced curriculum broken down into smaller steps, effective use of questioning, and constant review of material through checks for student understanding.

As someone who teaches literary analysis to high school students, Rosenshine’s emphasis on reducing cognitive load for ‘novice’ learners in the initial stages of learning a new topic or skill is an idea that heavily resonates with me. When we initiate students into the world of applying a critical lens to poetry, short stories, novels, or plays, there are multiple aspects that we want them to master. These include, but are not limited to, an understanding of the explicit and implicit meaning of the text, a familiarity with the context, an engagement with the writer’s craft and the effect on readers, and an appreciation of the interaction between form and content. At the same time, we also want our learners to acquire skills such as the ability to form and organise arguments, to identify textual references that support their arguments, and to use appropriate academic register in their analysis.

Admittedly, this is a big ask! Good for us, then, that the pedagogical efficacy of using models and exemplars lies in its very ability to transform such big asks into concrete, step-by-step learning experiences that become a part of the teacher’s modelling (I do), the guided practice opportunities built for students (we do), and the independent tasks the students work on (you do).

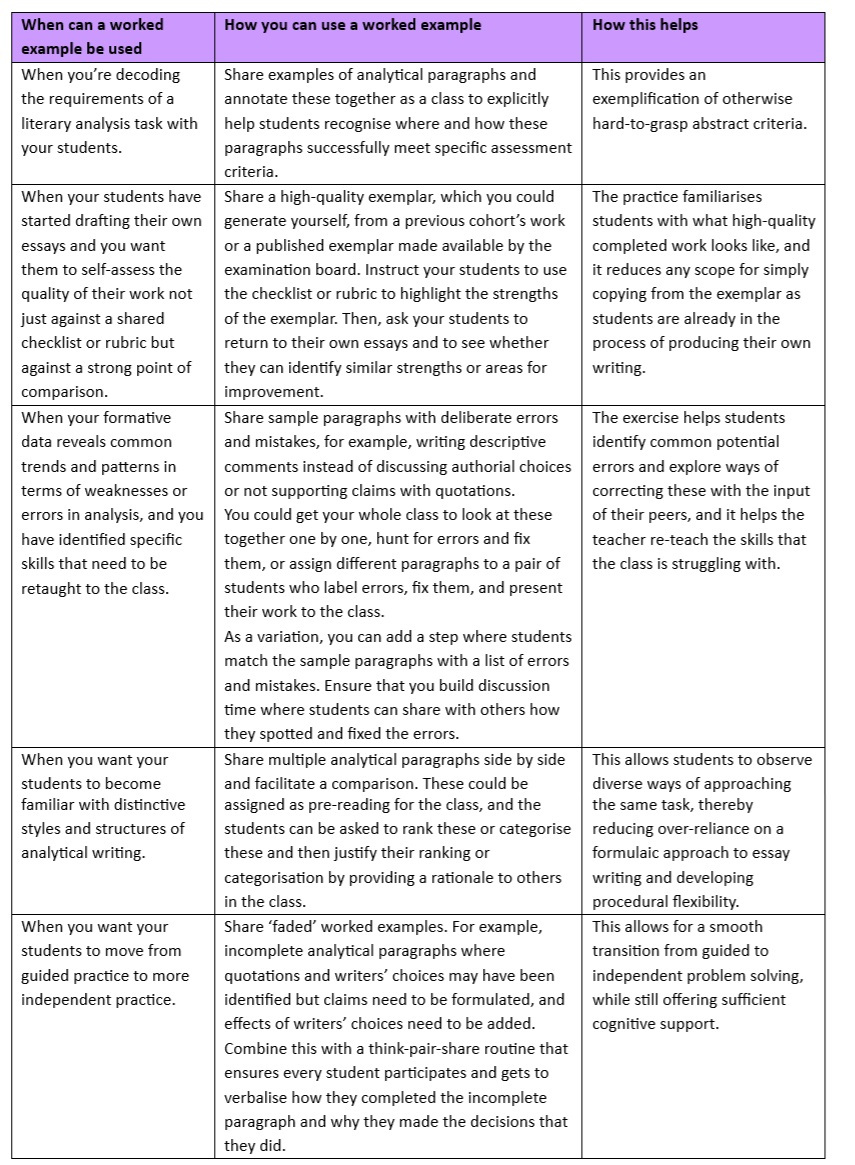

There are multiple ways in which we can use worked examples in the literature classroom. In my experience, the most crucial detail to remember is that the use of examples becomes productive for skill acquisition and consolidation when teachers intentionally make time and protocols for students to discuss the steps followed in the example and add thinking prompts that allow students to focus on the example’s strengths and weaknesses.

For a subject such as literature, we need to acknowledge that sample essays can end up becoming counterproductive if they create a formulaic approach, reduce student creativity, or lead to passive exposure to ready-made responses. At The British School, New Delhi, we have found that literature teachers can consciously guard against these pitfalls by designing learning experiences around worked examples that centralise learner agency. These can include independent and group annotations of sample essays, ‘think-alouds’ where students explain the step-by-step process, use of visible thinking routines, and probing questions that prompt students to actively engage with the exemplar instead of passively consuming it.

The suggestions below for using worked examples for teaching literary analysis are derived from classroom practice and from the valuable insights of researchers and writers (including Renkl et al., 2000; Cerbin, 2015; and Chen et al., 2023).

References and related reading

Cerbin, W. (2015). Worked examples. In Teaching Improvement Guide. University of Wisconsin at La Crosse Center for Advancing Teaching and Learning. https://www.uwlax.edu/catl/teaching-guides/teaching-improvement-guide/how-can-i-improve/worked-examples/

Chen, O., Retnowati, E., Chan, B. K. Y., & Kalyuga, S. (2023). The effect of worked examples on learning solution steps and knowledge transfer. Educational Psychology, 43(8), 914-928. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2023.2273762

Hawe, E., Dixon, H., and Hamilton, R. (2021). Why and how educators use exemplars. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.3.10

Renkl, A., Atkinson, Robert K. & Maier, U. (2000). From studying examples to solving problems: Fading worked out solution steps help learning. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2398854_From_Studying_Examples_to_Solving_Problems_Fading_Worked-Out_Solution_Steps_Helps_Learning

Sherrington, T. (2019). Rosenshine’s Principles in Action. John Catt.

How do you help your students to become independent learners? Do you offer them enough time to discuss their work with peers?

In this article, Ima Kazmi shares several suggestions for using worked examples to teach literary analysis. If you are a literature educator teaching these skills, look at the list of suggestions and choose one to introduce into your own practice. Reflect on the outcome with colleagues.