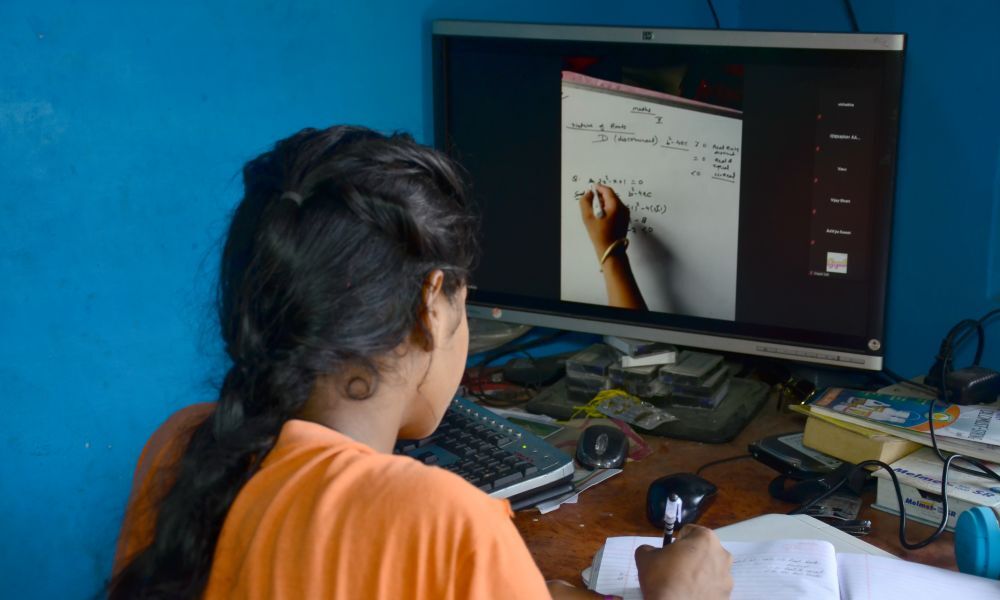

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, wherever possible the education sector has tried to adapt to online teaching, digitisation, ed-tech applications, and a previously unimaginable teaching regime. The teaching community has embraced improvisation, resource management, and a new work-life balance resulting in a resilient education system.

I was personally intrigued by the pace at which some of these changes took place, the courage of teachers in dealing with public scrutiny, and their openness to learning from all sources including students and parents.

Recent developments in the educational landscape led me to conduct a study involving hundreds of teachers across private schools in Delhi, including Ahlcon International School, where I work. The research questions and the findings and analyses are summarised below.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic brought changes in the ed-tech sector?

The emergence of start-up ed-tech firms has revolutionised the way teachers interact and make their classes engaging. The pandemic witnessed a rise in rapid teacher upskilling and the availability of quality tech applications. One teacher commented, ‘We achieved in three months what we struggled with for the past three years − adapting to new technologies in classrooms.’ Technology helped in curating content, imparting skills and values, storage and dissemination of assignments, and reporting and evaluation.

What practices did teachers adopt to boost students’ wellbeing during online teaching?

Technology helped connect students and teachers, blunting the depressing impact of isolation and home sheltering. Teachers shared videos on mindfulness, yoga, and inspirational and positive thinking that helped students remain calm, focused, and optimistic.

When teachers met students online, discussions on personal experiences, peer-to-peer interaction, student-led self-help groups, and empathy-building became priority. Tech applications for classroom collaboration − polls and surveys, breakout room facilities, and quizzes and games − helped make the online learning experience closer to an in-person environment.

Academic learning may have suffered, but many teachers compensated for it by introducing activities that encourage the development of socio-emotional skills, creativity, communication, critical thinking, and digital skills.

It is heartening to note that student wellbeing, managing emotions, and student-led classes are becoming a priority for educators. Asking questions on character strengths, how to deploy coping skills, helping and valuing friends, and identifying dominant emotions through tech-enabled online tools acted as a bulwark against fear, grief, and declining confidence during the pandemic.

Teachers in the study highlighted that monitoring children’s activities during online engagement became a significant challenge for parents. This was further compounded when parents returned to their workplaces. On the other hand, children complained about the non-availability of quality entertainment opportunities, a lack of group activity, and extended screen time.

How can ed-tech players meet the expectations of parents and students?

Ed-tech companies will have to innovate and invest in products that cater to new expectations of all stakeholders. Participants in the study felt that classroom friendly versions of learning management systems that allow seamless embedding of learning materials and formative assessment tools would be in high demand. A synchronous learning experience, whether online or in-person, will not remain the same. Meeting the needs of the person (learner) through personalised instruction (assisted by technology) will be the new ask for the tech application developers.

The shift from digital to on-campus studies will be gradual. The pandemic has produced student and teacher ambassadors of apps developed by both known players and start-ups. Therein lies an opportunity for developers to learn from classroom insights, develop applications that respond to low bandwidth, and place transformational technology in the hands of students and teachers.

Our study showed that teachers felt strongly that the next growth cycle of technology innovation would focus on e-learning content to promote equity, social entrepreneurship, values-driven e-projects, and sustainability.

What are some of the challenges for educators as schools reopen?

In the wake of the school shutdowns, huge learning losses and discontinuities have taken place, affecting the most marginalised and vulnerable.

A recent study points out that children are on average six months behind in mathematics and reading. It also notes that even where schools had functioned nearly a hundred per cent in-person, parents had reported thirty per cent learning loss among their children due to mental worries, troubling reports of the pandemic, and the fear of the virus. In situations of a hundred per cent virtual schooling, learning losses were reported to be sixty per cent. Additionally, mental and emotional health issues are mounting.

As students return to schools in phases, the possibility of a blended learning approach increases. We have to accommodate all students, give choices, and consider their digital maturity, personal circumstances, and curricular needs to determine the extent of blending required in future.

The primary concern of teachers will be bridging learning gaps when students return to schools. The transition from the brick and mortar to the virtual space was difficult in the early days of the pandemic, but reversing that under a looming possibility of a blended approach to teaching looks even more daunting.

Learners are used to online activities, and the comfort and routine associated with them which indicates that teachers will have to innovate new approaches to pedagogy once children return to schools.

What could be some education models as schools reopen?

The overwhelming response from the study suggests five plausible models of student engagement.

One, blended learning, where students attend full-time classes in person, and an element of online teaching is embedded in the schedule.

Two, virtual learning, where students attend a school virtually full-time, and teachers teach virtually.

Three, a hybrid model, where students attend a school in person on certain days and virtually on other days in a week.

Four, a flexible hybrid model where students can choose to attend a school in person or virtually on a given day based on their personal needs and content delivered.

Five, a flexible blended model where students attend a school in person for 3-4 days a week and choose to attend the school in person or virtually or work on their own or with peers for the remaining days of the week.

The author gratefully recognises the contributions of colleagues, Mayank Dugar, Sumedha Sodhi, Priyanka Tiwary, Sunanda S. Kumar, Deepti Chopra, Risha Imran, and Monika Khanduja in administering the questionnaire, analysing results, and giving insightful inputs. Author also appreciates the management of the Ahlcon International School, Delhi for supporting this research.