In this article, Deepali Dharmaraj explores the role of feedback in the context of peer observation and identifies key principles and practices that enable the experience to be mutually beneficial for both the observer and observed.

In a previous article, we looked at peer observation as an important component of collaborative continuing professional development. Feedback, in the context of peer observation, should be different from that of an evaluative observation where feedback can be directive and provide suggestions for improvement in order to meet predetermined performance indicators.

In addition to the difference in purpose – development versus evaluation – three components can strengthen feedback, make it more robust, and enable feedback to ‘stick’ with both colleagues. The objective is to ensure that feedback stays on with colleagues and results in improving practice. Ultimately, this will raise the quality of teaching and learning in the classroom, which in turn will have consequent benefits for learners. Before delving into the process of feedback, it is important to outline these prerequisites that enhance the process.

Relationship

Having an established professional relationship before engaging in peer observation is important. Colleagues, for example, may be from the same institution, or have worked on a project together, attended the same training course, shared reading materials, or collaborated on a lesson study. A shared history is the foundation of being able to have an open and honest discussion following the lesson observation.

Taking it one step further, is playing the role as a critical friend whom Costa and Kallick define as ‘a trusted person who asks provocative questions, provides data to be examined through another lens, and offers critiques of a person’s work as a friend. A critical friend takes the time to fully understand the context of the work presented and the outcomes that the person or group is working toward. The friend is an advocate for the success of that work’.

Credibility

Defined as the quality of being trusted and believed in, credibility is a key principle for giving feedback. Sharing our own lived experiences and what we have done in practice builds credibility and enables the uptake of feedback, i.e. of having ‘walked the talk’. At the same time, credibility also involves being able to acknowledge and admit gaps in our own experience and knowledge and having an attitude of lifelong learning.

Review

Michael Chiles highlights the importance of not stopping at the event of giving feedback. According to him, follow-up determines the power of feedback. In the context of peer observation, this could include the obvious direct follow-up in the form of a discussion after some time has elapsed. However, follow-up can also be a reversal of roles in a subsequent peer observation or sharing learnings from the process with other colleagues. Follow-up is thus intended not as a way of policing but of strengthening the relationship between two colleagues and improving their teaching practices further.

In a study conducted in 2012, Hendry and Oliver cautioned that ‘receiving feedback was also perceived to be useful but not more beneficial than watching a peer teach’. Thus, a feedback session has to be designed carefully to ensure that both teachers mutually learn from each other and becomes as important as the exercise of peer observation. The post-lesson feedback discussion can be a space for colleagues to have an open and honest discussion about a peer observation session and requires active involvement from both parties. This phase of the cycle can be further divided into three separate units: before, during, and after the discussion and there are some useful practices that can be adopted to make the process mutually beneficial.

Enhancing benefits of feedback

As an observer, before the discussion, consult your colleague to understand whether the post-lesson discussion should be conducted immediately after the lesson or whether the teacher would like to delay it, perhaps by a couple of days, to reflect on the lesson. Refer to the pre-lesson discussion and focus on areas that were identified and prepare what you are going to say by writing down your reflections and observations. It is common to be drawn towards giving suggestions or advice and feeling that you need to have all the answers ready. As a teacher, it is common to be overly self-critical, but it is equally important to articulate what went well.

In addition, think about the students when planning the post-lesson discussion. As an observer, you may, for example, have noticed that a learner was distracted or had a ‘blank stare’. Sometimes communicating classroom observations to the observed teacher is useful. A teacher may have intuitively felt that a learner was struggling with a concept but being in the moment could not address it. Peer observation provides the opportunity of having had an additional resource in the classroom to help teachers unpack missed nuances.

During the discussion, as an observer, seek to understand and listen instead of starting by giving your opinion. It can be useful to begin a feedback discussion by asking your peer to reflect on the lesson and describing to what extent learners met the outcomes defined. This enables the observee to have more control and accountability in the process.

For both colleagues, using tentative language and modals – ‘Could you have/I could have...’, ‘You may be able to...’ − can help the process be less like a value judgement. As an observer, using open-ended questions such as, ‘How could you have given your instructions differently?’ instead of saying ‘Did you give clear instructions?’ facilitates further discussion in a non-threatening manner.

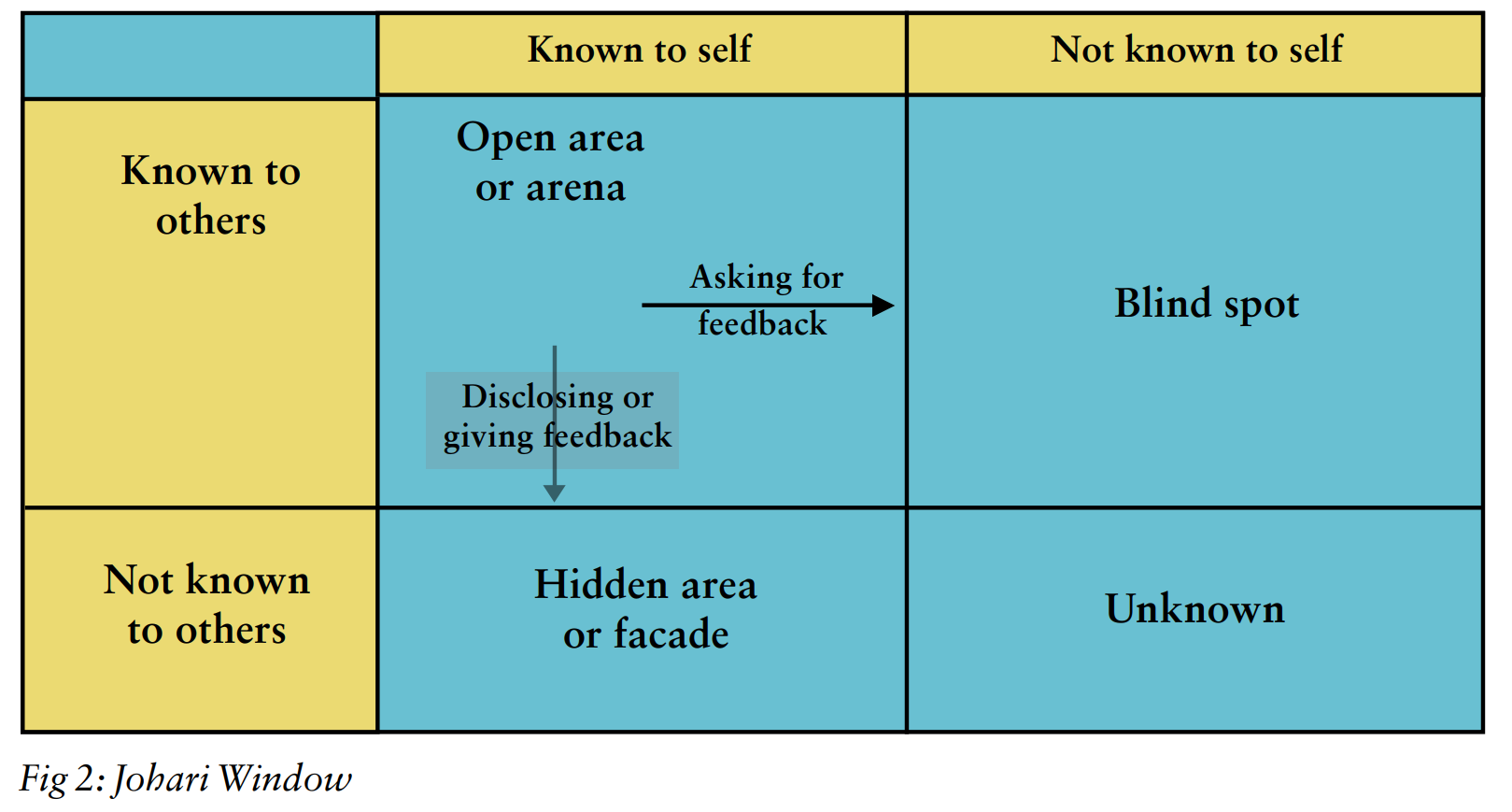

As the observed teacher, make use of the additional expertise to find out what is actually going on in your classroom. For example, what were students doing when your back was turned? The Johari Window principle (shown above) can be used effectively in this situation by enabling us to see our blind spots and increases our open area. Finally, do not hesitate to go off-script or disagree during the discussion if that is necessary. The notes both teachers make can serve as a guide but discussions that are organic and spontaneous can be richer and more meaningful.

After the discussion, both teachers should come up with a collaborative action plan. It is common to have the observed teacher list out actions they will take, but in the context of peer observation, it is equally important that the observer does that too. A useful format to follow is identifying one exercise or practice that you could start doing, one that you should continue doing, and another one that you should stop doing.

By following such routines, peer observation can become a rich source of continuing professional development, for both the observer and the observed to collaboratively support each other in improving their practice and becoming better teachers.

A version of this article first appeared in the print magazine Teacher, distributed in India, in April 2021.

References

Cambridge Assessment International Education. Getting started with peer observation. https://www.cambridge-community.org.uk/professional-development/gswpo/index.html

Costa, A. and Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(2), 49-51.

Hattie, J. (2011). Feedback in schools. In Sutton, R., Hornsey, M. J., & Douglas, K. M. Feedback: The communication of praise, criticism, and advice. Peter Lang Publishing. https://www.visiblelearning.com/sites/default/files/Feedback%20article.pdf (PDF, 128KB)

G. D. & Oliver, G. R. (2012). Seeing is believing: the benefits of peer observation, Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 9(1), 1-9. https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutl/vol9/iss1/7

Naylor N. (2020, June 5). Interview with Michael Chiles [Audio podcast]. https://anchor.fm/naylorsnatter/episodes/The-CRAFT-of-Assessment-with-Michael-Chiles-eeuq8t

G. (2007). The Hidden Lives of Learners. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Tenenberg, J. (2016). Learning through observing peers in practice. Studies in Higher Education, 41(4), 756-773.