In a recent Teacher article, Learning Specialist Jeanette Breen shared how Templestowe Heights Primary School (THPS) in Victoria has improved its writing moderation process. Here she describes a new step that aims to bridge the gaps that still exist for staff, through an assessment process known as comparative judgement.

If you have ever sat in a writing moderation session, you would have some awareness of the holes in this approach. While moderation is promoted by education departments and is commonly run as professional development, teacher bias and inconsistent use of rubrics can make it ineffective.

This was the impetus that led to an inquiry into a more accurate measurement process for student writing at THPS in Melbourne. It is a significant step in vulnerability to review something that is painstakingly created as a scaffold for a school context, like the assessment rubric for writing at THPS – but it was not producing the outcomes we wanted in assessment and needed a transformation.

Reshaping moderation and writing progressions

It is worth reviewing the thinking of Dylan Wiliam, where he discusses that rubrics are most useful when their intention is to improve learning, not the accuracy of assessment (William, 2018). This has been our finding. Even though we thought to create clarity on descriptions of quality, judgements were just as varied as they had been before we made the rubric.

Through our exploration into quality assessment, we have realigned our thinking and purpose. The writing rubric became the writing progression and its reason for existence is primarily to assist teachers and students in understanding what learning is needed next.

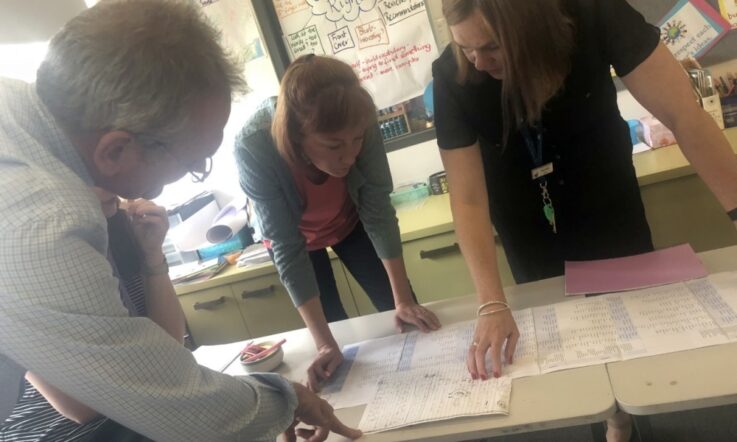

Our moderations now have shifted intention toward providing an opportunity for teachers to view writing cross-level, develop shared vocabulary and create learning sequences for a progression of skills benchmarked at each level. Assessment is no longer its purpose, clarity in a learning progression that we modify and sequence our teaching with is a far better use of professional development time.

This left an open space however, in our journey with writing assessment, mentioned in my previous article.

A shift in writing assessment leads to a project

The search for a method of assessment that allows us to think with more consistency about open-ended writing has led to THPS gathering schools for the Australian Writing Assessment Project, to trial a technique called Comparative Judgement (CJ).

When, as educators, we question the purpose of something we are used to with a view to finding a better way, it leads to some uncertainty and risk. The trial and error associated with an open inquiry into change engagement is something that leadership at THPS, and other schools involved in this assessment project, are demonstrating an openness to (Timperley et al., 2020).

Asking students to write is one of the most challenging things we require of them in the classroom (Hochman & Wexler, 2017). Writing is a deeply cognitive task that demands integration of a number of processes. Assessment therefore, is paramount to monitoring how effective our instruction is on student learning.

In an Australian context, NAPLAN (National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy) provides one of the few opportunities to measure our student writers – and therefore our teaching – against a standard. The work of Daisy Christodoulou provides some reference here (Christodoulou, 2016).

The project is a collaboration between THPS and 24 Australian schools, with Dr Chris Wheadon and Daisy Christodoulou, of UK-based company No More Marking. As we track the progress, thinking and data of this endeavour it is important to explore in depth exactly what CJ is.

What is comparative judgement?

‘Comparative Judgement simply asks each marker to make a series of judgements about pairs of tasks … the marker looks at two stories and decides which one is better.’ (Christodoulou, 2016, p. 187)

It is a process that requires the assessor to make a relative judgement, not an absolute one. Teachers participating in the project will be asked to choose between two student samples, which one is better. This process is repeated with several judgements made by a number of teachers. Each decision is entered and, using an algorithmic technology process, a continuum of the student samples is formed.

The larger the body of student samples, the more likely we are in Australia to develop a nationally representative sample, allowing a scaled score to be aligned to an age. The future of the Australian Writing Assessment Project is the possibility of anchor points allowing teachers to measure writing by age and growth over several points in time.

One of the great advantages of CJ is the way that many judgements by many different teachers are combined together to produce the final measurement scale. With traditional moderation, 90-95 per cent of scripts will only ever be seen by one teacher – they are never actually moderated! But with CJ, the process is organised so that every script is seen 20 times. With traditional moderation, rogue judgement can be decisive, but with CJ, this will be cancelled out by the weight of the other judgements.

A moderation between schools

If the criticism of moderation is inconsistency in grading at one school, then a better technique would need to eliminate this. CJ is not reliant on the bias produced in one school’s judgement, or limited by the ceiling formed by one set of criteria (Wheadon, 2020). Most importantly however, CJ allows for moderation between schools, just like NAPLAN – the difference being that the data is not public and is immediate. It is therefore useful to schools in ascertaining what, in instruction and learning, is working or in deficit. Data that allow leadership to see the success of their writing frameworks and decisions, particularly when measuring their students against others, also provides opportunity for analysis of ways to fill gaps in writing proficiency.

In this trial, No More Marking organise the judging process so that 80 per cent of the time, a teacher will judge scripts from their own school. This will give them insight into the standards of the students they teach. The other 20 per cent of the time, a teacher will judge scripts from other schools. This gives them insight into standards from the other schools, and also allows for all of the students’ work to be placed on a consistent scale that is common to all the schools.

Also, a teacher will never be asked to compare a script from their school with a script from another school. This means a teacher cannot be biased in favour of their students, and also that they don’t have to worry about teachers from other schools being biased against their students – that simply cannot happen.

Efficiency and reliability

Time is precious at school. Teaching has been compared to a clinical profession where diagnosis and intervention of not just one, but a whole class of individuals is a constant cycle. Added to that, the requirements of professional development and maintaining one’s own growth in knowledge is also a critical expectation. It is important then, that leadership do not waste teachers' time on assessment processes that are not purposeful.

Evaluating writing, as discussed earlier, becomes a simple and efficient process with CJ. A judgement session with teaching staff could take up to an hour and, due to the mobility of technology, could be synchronously occurring in different locations.

How do we know it is reliable? The findings from projects similar to ours is that regardless of experience level, teachers inherently know whether a writing piece is quality. They do not need the criteria, knowledge or a rubric to explain it. CJ allows decisions to be made without the need of a measurement tool. It is simply about choosing one over another. The analysis of the mechanisms within student writing can then occur after it has been aligned within the continuum.

What impact are we hoping for?

Besides the integration of a more efficient and accurate assessment approach, we hope to also understand how this process could be formative. When we as a project of schools receive our data from No More Marking, can we align it to teaching sequences at student point of need? Can we intervene and shift outcomes and monitor our student growth in ways that we were unable to before? Can we, as a community of practice, better embed writing instruction that sees students flourish as writers?

Emerging global data suggest that writing instruction in most classrooms is not sufficient. (Graham, 2019). For those of us who live in Victoria, our student samples and data will be an interesting review based on being the only state with two terms of remote learning. Our national data on boys’ writing, indicates that large gender gaps exist (Baker, 2020). What will the No More Marking data reveal that could assist learning within this landscape?

These curiosities are an open space. Schools in the project will have access to explicit professional development opportunities, networking and webinars on offer with Daisy Christodoulou to explore such questions and interrogate their data with integrity.

At THPS we look forward to sharing the evidence of impact in our narrative from the ‘Assessing Australia’s Primary Writing Project’ as we begin this exploration.

With thanks to Daisy Christodoulou for additions and feedback.

Stay tuned: Jeanette Breen will be sharing regular updates about the project through Teacher.

References

Baker, J. (2020, August 30). One in five year 9 boys below minimum writing standard: NAPLAN review. Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/one-in-five-year-9-boys-below-minimum-writing-standard-naplan-review-20200828-p55qeb.html

Christodoulou, D. (2016). Making good progress? The future of Assessment for Learning. Oxford University Press.

Graham, S. (2019). Changing how writing is taught. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 277-303.

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2017). The Writing Revolution: A guide to advancing thinking through writing in all subjects and grades. Jossey-Bass.

Timperley, H., Ell, F., Le Fevre, D., & Twyford, K. (2020). Leading Professional Learning - Practical strategies for impact in schools. ACER Press.

Wheadon, C. (2020, July 2). Handwriting Bias. The No More Marking Blog. https://blog.nomoremarking.com/handwriting-bias-ab81b6cc7629

Wiliam, D. (2018). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.