‘Students are uniquely placed to bring to conversations something which only they can, their lived experience of what it means to be a learner in their school.’ In today’s article, John Cleary asks if ‘student voice’ is enough, and discusses how educators and school leaders can instead partner with students to ensure their voices (and views) are heard and acted upon.

You may have recently found yourself reading an article or social media post where the importance of the voices of students was celebrated. The term ‘student voice’ is one which is heard regularly in education discourse at the local, network, education system and national level.

The importance that the voices of students be heard is a position on which there is almost universal agreement between teachers, leaders, policy makers and students themselves. Students are uniquely placed to bring to conversations something which only they can, their lived experience of what it means to be a learner in their school.

But is ‘voice’ enough? At its best, the term may be well intentioned but is perhaps insufficient to capture the richness of the work currently underway both here in Australia and internationally. This work includes partnerships in which students and teachers not only share their unique perspectives but also work together to shape responses to the opportunities and challenges they identify.

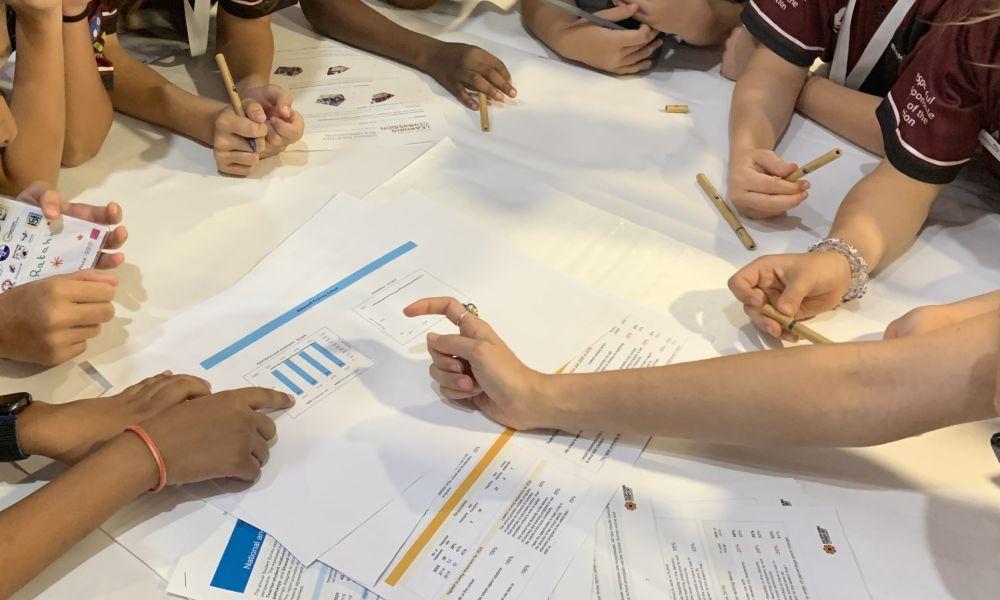

This can be seen in the collective development of an individual or personalised learning plan or may even be at a whole school or network level where students are working alongside adults to design, test and refine strategies to respond to an identified need.

At its least helpful, the term may be invoked for experiences where students come together for one-off or largely performative events with a great photo opportunity to round off the day. They might get a branded t-shirt, returning to school with the message that they have ‘the power to change the world’.

All too often, however, students return following these programmatic experiences to environments where they find their voices are unable to influence the way in which they experience education each day. Changing the world can feel like a distant possibility when you discover that you are unable to influence the way you receive feedback on your most recent assessment task.

Is ‘voice’ enough in these scenarios and what is the role of adults in partnering with students to ensure their voices and views are not only heard, but acted upon? Lundy (2007) identifies that children’s enjoyment or successful experience of Article 12 with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) – namely ‘the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child, (UNCRC, 1989, p.4) – is dependent on the cooperation of adults.

The reluctance of adults to engage with opportunities which privilege the views of young people may be as a result of previous engagements with programmatic or tokenistic ‘student voice’ experiences where, although they engaged genuinely in the opportunity, this participation did not lead to any real change in either the practices of their colleagues or the lived experiences of learners at their school.

Lundy also argues the reluctance of adults to engage in opportunities which bring Article 12 to life, may be connected to 3 concerns: ‘scepticism about children’s capacity (or belief that they lack capacity to have a meaningful input into decision making); a worry that giving children more control will undermine authority and destabilise the school environment; and finally, concerns that compliance will require too much effort which could be better spent on education itself.’ (2007, p. 929).

Children and young people as partners in decision making

A notable exception to these scenarios can be seen in the National Framework for Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-making (DCEDIY, 2021), led by the Irish Government’s Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth.

The framework is accompanied by guidance which exemplifies this participation in meaningful ways for policymakers, professionals and practitioners, academics and researchers and, importantly, children and young people themselves.

The framework seeks to provide resources to support each partner as they consider the ways in which young people can participate meaningfully in decision making, whether that is at their local sporting club, in the classroom, or when working alongside a government in supporting policy design.

Importantly, the framework acknowledges the importance of voice, but also that by itself this is not sufficient for effective participation to be possible. It describes a focus on 4 distinct, albeit interrelated, elements: space, voice, audience and influence (DCEDIY, 2021).

What is meant by ‘a partnership’ with students?

The term ‘partnership’ represents the commitment required by policymakers, leaders and educators to ensure students can participate in educational decision-making – whether in their own classroom, school or education system, diocese or network.

Despite a broad agreement that this is worthwhile, our youngest learners are one of the groups who have traditionally been least likely to be involved in decision-making in their own lives. This may include perceptions that young children may lack the maturity to be able to form valid opinions about the world around them (Ferreira et al., 2018); and a lack of capacity or understanding on the part of adults on how to create meaningful opportunities (MacNaughton et al., 2007); or a wish to shield children from what adults may describe as complex issues (Peters, 2020).

Over the last 2 decades of my own experience of learning about this work as a classroom teacher, school leader, senior executive and researcher; a consistent reflection of adults who engage in partnerships with students is that hearing students speak about and use the language of improvement, significantly impacts on their mindset and perceptions of what students are capable of. Most commonly, adults’ first reflection is to say, ‘I didn’t think students could talk about learning that way’.

As a teacher, the work of Black and Wiliam (1998) and their publication Inside the Black Box was personally transformative in introducing a range of practices to enhance the self-esteem of pupils, their role in self-assessment and the partnership between teacher and student to achieve individual improvements, positioning this partnership as profoundly social and personal – but one that ultimately is ‘driven by what teachers and pupils do’ (1998, p. 14).

It may be that engaging in partnership work with students is about putting behaviour before beliefs. Engaging in a partnership with young people in good faith can provide the experiences which change the beliefs of those involved.

However, it is critical that the processes and tools used in the design of these experiences are carefully considered and adapted to reflect the culture, context and current practices of your classroom, school or network. Engaging with enthusiasm is helpful, but not sufficient.

Poor experiences for adults and young people also run the risk that both parties will be less likely to engage in worthwhile opportunities in the future.

A pedagogy for student partnership in school improvement

In my own work, I explore the characteristics that have been reported by students, educators and school leaders as making these partnerships transformative. These reflections are available through my recent conversation with the Art of Teaching podcast (Green, 2025), and in my recent publication with my long-time partner in this work, Summer Howarth, (Cleary & Howarth, 2024).

The P⁴ Model (Cleary, 2024) describes a partnership to the power of 4 (including students, educators, leaders and policy makers), through the 4 domains of Purpose and Alignment, Process, Perspective and Place and Power and Co-Creation. The model explores the characteristics within each domain and provides practical examples of their application, using examples from my work with the Northern Territory Learning Commission (NTLC). The NTLC is a model which represents the participation of learners from a number of geographically, culturally and linguistically diverse school communities across the 1.35 million square kilometres of the NT.

Being clear on the roles and responsibilities of all partners is key

A well-intentioned but unhelpful feature of some ‘student voice’ initiatives includes adults describing that the work is ‘all about the kids’. In positioning students as leading alone, adults can unintentionally position themselves as passive participants in this work.

The opposite must be true, but it is important to be clear on the roles and responsibilities of all involved, as well as the deep and specific expertise that each partner brings.

In the same way that adults cannot claim to fully represent the positive and negative experiences of the learners they work alongside each day, students can also find it difficult to translate these experiences into the changes in pedagogy required to improve learning and engagement outcomes in the future.

The role of the school leader and how they speak about this work is critical. For those who describe the importance of ‘student voice’ but can only pop in at the beginning of scheduled times due to their busy schedule, they miss the opportunity to deeply understand the rich perspectives students bring.

The crucial role of leaders in this partnership cannot be delegated, and those who do risk unintentionally signalling it as unimportant to other adults in their school community.

Leaders bring the ability to connect the experiences students share to a whole-school improvement agenda, ensuring the necessary time, space, resources and tools are present to support a partnership between teachers and students to fulfil its significant potential.

Beyond ‘voice’ to ‘partnership’

Moving beyond voice means acknowledging the importance of the views, rather than only the voices of young people but also that by itself, hearing these voices is not enough.

Moving towards a partnership with students involves enacting pedagogies and processes which support learners to share their rich perspectives on what currently might be so but also activates the deep expertise of adults alongside students, exploring what might be possible in strengthening the engagement, growth and achievement for an individual student, but also for other learners across a school community.

References

Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment. Granada Learning.

Cleary, J. (2024). A Pedagogy for Student Partnership in School Improvement: Factors that Students and Educators Participating in the Northern Territory Learning Commission Identify as Transformative in Nature. [Manuscript in preparation for Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne].

Cleary, J., & Howarth, S. (2024). Beyond Voice: Students as partners in improvement. CSE Leading Education Series: June 24.

Green, M. (Host). (2025, March 29). John Cleary: Beyond Voice: Students as Transformative Partners in Education. [Audio podcast episode]. The Art of Teaching. https://theartofteaching.podbean.com/e/john-cleary-beyond-voice-students-as-transformative-partners-in-education/

Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth (DCEDIY). (2021). National Framework for Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-making. Rialtas nah Eireann. https://hubnanog.ie/participation-framework/

Ferreira, J. M., Karila, K., Muniz, L., Amaral, P. F., & Kupiainen, R. (2018). Children's Perspectives on Their Learning in School Spaces: What Can We Learn from Children in Brazil and Finland? International Journal of Early Childhood, 50(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-018-0228-6

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927-942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

MacNaughton, G., Hughes, P., & Smith, K. (2007). Young children's rights and public policy: Practices and possibilities for citizenship in the early years. Children & Society, 21(6), 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2007.00096.x

Peters, L. (2020). Activism in their own right: Children’s participation in social justice movements. In S. A. Kessler & B. Swadener (Eds.), Education for social justice in early childhood (pp. 87-99). Routledge.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, November 20, 1989, https://www.unicef.org.au/united-nations-convention-on-the-rights-of-the-child

Are you clear on the experiences of student voice, agency or leadership initiatives which different students and staff may have previously been engaged in? What are their reflections on the impact and success of these opportunities?

Can you think of examples which draw on a partnership with students for improvement in your own classroom, team, school or network? How do participating students and educators experience this partnership? What do they find to be the most valuable aspects and methods used within its design?