In order to better respond to the learning needs of students, Emmaus Christian School in Canberra has moved to a new model of classroom integration for Teaching Assistants. Here, Head of Secondary School Luke Willsmore, and Dr Tanya Vaughan and Susannah Schoeffel from Evidence for Learning, discuss the new way of working and the research that informed the change process.

The key message which emerges from the research about the use of Teaching Assistants (TAs) is that when they are well trained, well deployed and strongly supported, we are likely to see positive impacts on students' achievement.

Studies exploring this impact provide us with a complex and sometimes challenging picture (Education Endowment Foundation, 2020b; Evidence for Learning in collaboration with Melbourne Graduate School of Education, 2020). In some settings and under particular implementation conditions, TAs (known in some settings as teacher aides or integration aides) add significant value to students' learning, although if not carefully implemented they can lead to students becoming over-reliant.

We've explored the variation between studies in a previous Teacher article ‘The effective use of teaching assistants', and since then additional research has strengthened our understanding of effectiveness. To provide support for schools who are exploring the role of TAs, Evidence for Learning (E4L) has released a Guidance Report which contains seven actionable recommendations drawing from the evidence of what is most effective in maximising the impact of TAs (Evidence for Learning, 2019).

Last year, E4L co-designed and facilitated the Evidence into Action professional learning series. Established with the Association of Independent Schools of the ACT (AISACT), it provided schools with a year-long program to support the development and evaluation of school improvement initiatives. Head of Secondary School at Emmaus Christian School, Luke Willsmore, was amongst the first cohort to engage with the Evidence into Action professional learning series, and for him it came at just the right time.

An impetus for change

Emmaus Christian School is a small but growing K-10 school in Canberra, with roughly 475 students. Many factors came together to create the impetus which led the school to reassess how students' needs were being met, particularly those students who required additional learning support. There was excellent practice occurring across the school, but the feedback from staff, parents and students was that the model for supporting students could be improved.

About 13 per cent of students across the school require modifications, which means they are eligible for some form of learning support beyond regular differentiation within class. Many students in the secondary school who were offered support had been refusing it, not wanting to be withdrawn from the class or given ‘special attention'. At the same time, the school was beginning to experience growth in student numbers beyond what was expected, which put additional strain on existing resources and this existing model of withdrawing students from class.

Exploring and planning a new approach

Prepared with evidence from the Teaching & Learning Toolkit (Education Endowment Foundation, 2020a), Luke engaged with the school leadership team in designing a revised model for supporting students. The impetus was clear, and an approach began to form.

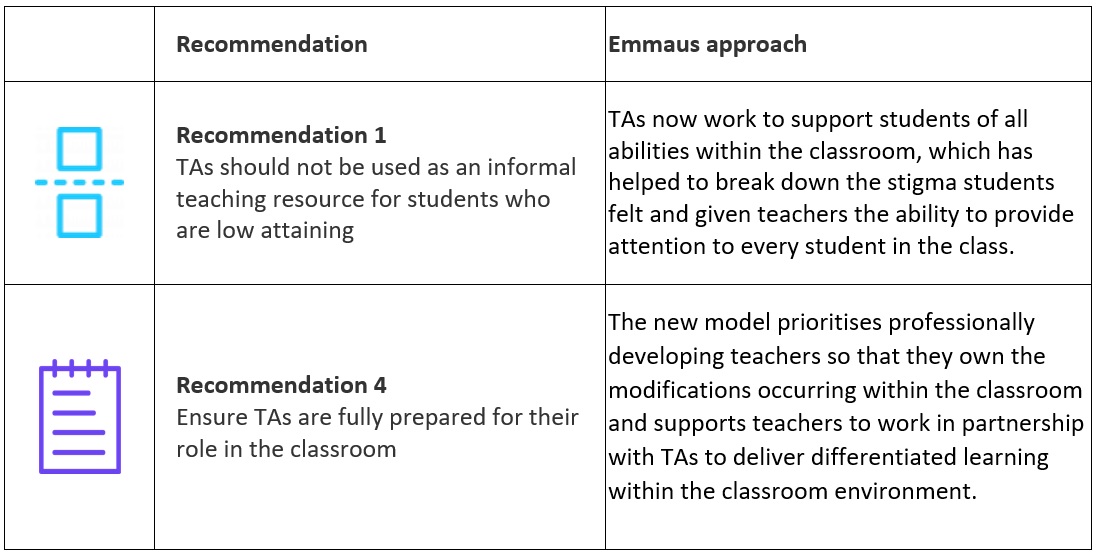

Essentially, the plan was to move away from the existing model of support, which relied heavily on students being withdrawn from lessons, to an integrated approach which would encompass the entire class. Although the E4L Guidance Report had not been published when Luke set out to design a new approach, his own understanding of the evidence drawn from the Toolkit closely mirrors several of the recommendations.

Adapted from Evidence for Learning (2019)

For many in the school, the changes felt ‘sensible', or like ‘common sense', and the leadership team continued to be informed by evidence. The outcome was a new design which was both well-received by the school community, and rigorously backed by the evidence of what had worked elsewhere.

The value of having a clear process for implementation (Sharples et al., 2019) and leading change has come to be useful beyond just this project, and at Emmaus the team has used the same process from the Evidence into Action series to guide a number of other school improvement initiatives.

Implementing a new way of working

TAs were engaged more centrally in classrooms, working alongside teachers, rather than withdrawing students from the classroom. The strengths of staff were considered, and a reorganisation coordinated to play to those skills. Part of this plan was to increase the number of TAs available within the school – a significant investment in an area that the school saw as impactful.

The early engagement with the staff ensured that there was strong buy-in from most of the staff. The leadership team found that teachers were positive about working in a new way with TAs, although it did initially require additional work as teachers took greater responsibility for modifications occurring for individual students. In the end, the TAs themselves were able to support students in an environment where that support was welcomed and weaved into what was happening in the classroom.

Outcomes and reflection

For Emmaus, this represents the beginning of a changing process that will continue to be adapted to the evolving nature of the school and in response to the needs of students. Now, over 12 months into the new model, Emmaus staff are seeing signs that the new approach is having a positive impact on students.

Secondary students, many of whom were refusing support, are now willing to engage with the TA in the classroom. In primary, it has been the classroom environment which has benefited from an additional adult now that TAs are integrated into classes. A range of behavioural needs in some classes had become disruptive and discouraging for teachers who felt alone in handling both the immediate wellbeing of students and learning of the whole class.

What could not have been predicted when Emmaus set out on this journey of improvement, was the benefit it would bring as the school faced the COVID-19 pandemic. TAs were present in two ways to support the students in response to the new reality. Many remained on site to support the students of essential workers and vulnerable students (a large number of these students happen to have additional learning needs) – parents shared their gratitude that it was the TAs who provided so much consistency for their children during this time. Others took their support role online, working within virtual classes, supporting both the teacher and students as they all navigated a new learning space.

Driven by early signs of promise, Emmaus has already taken steps to further reinforce this work by looking to add more TAs to its staff. It is an expensive exercise, but one the school values and it has prioritised the sustainability of this change in response to the positive indicators that have already been measured. Ongoing training and support for teachers goes together with the onboarding of new TAs, ensuring that maximum impact is felt in the classroom. This is another important element of the successful deployment of TAs (Butt, 2018; Education Endowment Foundation, 2020b; Evidence for Learning 2019; Evidence for Learning in collaboration with Melbourne Graduate School of Education, 2020).

Final thoughts

For schools considering reassessing how teachers and TAs work together, start first by understanding what current practice is occurring in your school. Like all educational approaches, this often comes down to the implementation of such a change which needs to be carefully planned in response to both the available evidence and specific needs and context of the school.

And, as the example of Emmaus illustrates, while the central aim of effective use of TAs is to have a positive impact on students' learning and achievement, the positive impact of an additional adult and supporting colleague for teachers should not be overlooked.

References

Butt, R. (2018). ‘Pulled in off the street' and available: what qualifications and training do Teacher Assistants really need?. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(3), 217-234.

Education Endowment Foundation. (2020a). Evidence for Learning Teaching & Learning Toolkit: Education Endowment Foundation. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/the-toolkits/the-teaching-and-learning-toolkit/full-toolkit/

Education Endowment Foundation. (2020b). Evidence for Learning Teaching & Learning Toolkit: Education Endowment Foundation. Teaching Assistants. Retrieved from https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/teaching-and-learning-toolkit/teaching-assistants/

Evidence for Learning in collaboration with Melbourne Graduate School of Education. (2020). Teaching assistants: Australasian Research Summary. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/the-toolkits/the-teaching-and-learning-toolkit/australasian-research-summaries/teaching-assistants

Evidence for Learning. (2019). Making best use of Teaching Assistants. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/assets/Guidance-Reports/Teaching-Assistants/E4L-Guidance-Report-Teaching-Assistants-Sep-WEB.pdf

Sharples, J., Albers, B., Fraser, S., Deeble, M., & Vaughan, T. (2019). Putting Evidence to Work: A school's Guide to Implementation. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/guidance-reports/putting-evidence-to-work-a-schools-guide-to-implementation

Does your school have a consistent approach to how TAs and teachers partner in the classroom to best support all students?

If you are considering adapting your approach to how TAs work in your setting, do you have a clear implementation plan to guide all staff in the new model?

Have you considered how to support students who have additional learning needs by providing them with more access to the classroom teacher?