Student learning gaps as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic school closures will be one of the biggest challenges facing leaders and teachers in the coming months. One-to-one and small-group tutoring have emerged as catch-up strategies.

While student safety and wellbeing is key, a focus on learning is critical. Students engaged in learning feel better about themselves, have more self-confidence and a greater ability to cope with life’s stressors and difficulties (OECD, 2017). Without successful participation in learning, it is likely that students’ wellbeing will not flourish.

An analysis by the Grattan Institute estimated that students may lose up to six months of learning over the remote learning period, with the equity gap predicted to widen at triple the rate (Sonnemann & Goss, 2020).

Funding for intervention packages

In Australia, for the first time, schools in several states will receive funding for tutoring to accelerate students’ learning in 2021 with the $250 million tutoring package from the Victorian Government, the $337 million New South Wales’ tutoring package and the South Australian Government’s online maths tutoring pilot program. Globally, there are similar policy responses, including the GBP350 million National Tutoring Program for government schools in England and the Netherlands’ funding for schools to implement tutoring interventions and other student services.

Modelling shows that, with these tutoring interventions, education systems could get learning back on track and even build back stronger from the crisis than before. A UK modelling analysis of Grade 3 student achievement data shows that remediation combined with long-term reorientation of instruction that aligns to students’ learning levels will not only fully mitigate the long-term impact of the COVID-19 related school closures but increase learning above the counterfactual (no school closures) by the time students reach Grade 10 by more than a full year’s worth of instruction (Kaffenberger, 2020). This data is compelling, and it tells us two things: Without mitigation, accumulated effects of disadvantage exacerbated by school closures related to the pandemic will have long-term impacts on students and schools; and tutoring alone is not sufficient – a commitment to reinforce remediation with the best teaching methods is critical to tackle the equity issue.

This presents a real opportunity to understand and close the equity gap, but effective implementation is critical for its success. Before implementing tutoring, a first step for systems and school leadership teams is to develop a clear plan to support, implement and then evaluate the impact and feasibility or acceptability. This is critical to understand the effect the tutoring program has in your specific school context.

Here is a summary of five key takeaways from best available evidence to guide schools’ decisions in implementing tutoring in 2021.

Why does tutoring work?

Evidence suggests that tutoring in one-to-one and small-group formats can help to improve learning, with positive impacts of up to five and four months’ learning, on average, respectively (Evidence for Learning, 2020a & 2020b). A recent meta-analysis of small-group tutoring showed substantial positive impacts of an Effect Size (ES) of 0.37 on learning outcomes (Nickow et al., 2020). There is evidence that tutoring is effective for a range of subjects. For example, Pellegrini et al’s (2018) synthesis of 23 maths tutoring programs found a positive impact of an ES of 0.20, or three months of learning impact, and tutoring has also been found to be very effective in primary reading (e.g. Inns et al., 2018 & 2019) and for secondary readers (Baye et al., 2017).

These results may not be surprising, because tutoring in one-to-one or small-group settings allow tutors to fully personalise the teaching to the needs of students. Such settings may, for instance, allow for rapid feedback and increased student engagement. With one to five students and decreased distractions, students have more time to practise and teachers could provide more individualised attention to help students overcome difficult problems, which may not be possible in the regular classroom.

Five takeaways from the evidence

1. Quality matters: Tutoring success will depend on the extent to which students receive extensive practise to master a small but targeted set of skills

One-on-one and small-group learning is fundamentally different from classroom education and may embody different pedagogical strategies. Students will need multiple opportunities to practise with immediate feedback in a variety of teaching and learning activities.

Some promising evidence suggests that small-group, targeted support for students struggling with particular skills needs to be comprehensive to include a small target set of skills and is well-structured for peer- and teacher-interaction rather than teacher-directed. The small-group reading program, Abracadabra (ABRA), for example, is a high-impact program that focuses on key skills of comprehension, vocabulary, fluency, phonemic awareness and phonics through individual, pair and group work (Abrami et al., 2020; Education Endowment Foundation, 2020). Teachers are trained to deliver lessons in a rotation of activities including whole-group instruction (e.g., story reading), followed by independent practise and work on its web-based program either individually or in pairs. Technology can be a good means for students to practice a specific skill, such as letter sound recognition, and has adaptive ability to provide immediate prompts and feedback according to students’ needs and pace, however it needs to be integrated with what is to be learnt and used to supplement traditional instruction (Ho, Vaughan & Deeble, 2020).

Quality teaching strategies that are used in regular classrooms such as clear explanations, scaffold and feedback, and peer collaboration should be present in tutoring sessions (Evidence for Learning, 2020c). Lessons should be explicitly linked to what students learn in the classroom, supported by teacher instruction and feedback. A review of after-school programs in the UK found that students studying together with teacher supervision and instruction had a greater impact than self-directed study sessions where students do homework together without the teacher (Pensiero & Green, 2017).

2. Individualisation alone does not make tutoring work, high quality feedback and support structures are critical for success

Approaches to individualised instruction also require strong teacher-student relationships and effective supports before, during and after class (Evidence for Learning, 2020c). Three “P’s” could be considered:

- Predictive: Use formative assessments to diagnose students who are not meeting expected benchmarks and develop individualised learning plans and goals according to their learning levels.

- Planned: Plan instruction and assessment that prioritise students’ success in achieving the essential skills needed for greater levels of complexity in regular classroom instruction and those that are more specific to each student’s needs.

- Proactive: Train and support to use assessments to plan, monitor and adjust instruction and activities according to students’ levels and needs. The aim should be to return students to regular classroom teaching and learning as soon as they have reached the set benchmarks.

3. Build tutors’ expertise and professional learning through coaching, mentoring and expert support

Evidence consistently shows the positive impact tutoring can have, when delivered by teachers, paraprofessionals (such as Teaching Assistants) or volunteers (Nickow et al., 2020; Baye et al., 2017). Although stronger effects are found for programs that are delivered by teachers and paraprofessionals, this implies the variability across tutoring programs is likely caused by other factors rather than the type of tutor. This suggests schools can be flexible about the use of tutors – using a mix of classroom teachers, paraprofessionals, and paid volunteers – but they should ensure a clear and consistent approach when implementing the intended plan.

Most effective tutoring programs have extensive professional development (Baye et al., 2017) as the skills needed for effective tutoring is different from classroom teaching. Pellegrini et al’s (2018) meta-analysis of maths tutoring programs found greater effects when professional development targets classroom management and learning engagement skills, as compared to content and pedagogy. This suggests that skills needed for effective learning such as motivation, engagement and metacognitive strategies should be a focus of tutoring. Tutoring programs that had limited focus on professional development (less than 15 hours) of teachers or paraprofessionals showed non-significant impacts (Pellegrini et al., 2018).

4. Implement tutoring sessions within a school-based response to intervention strategy

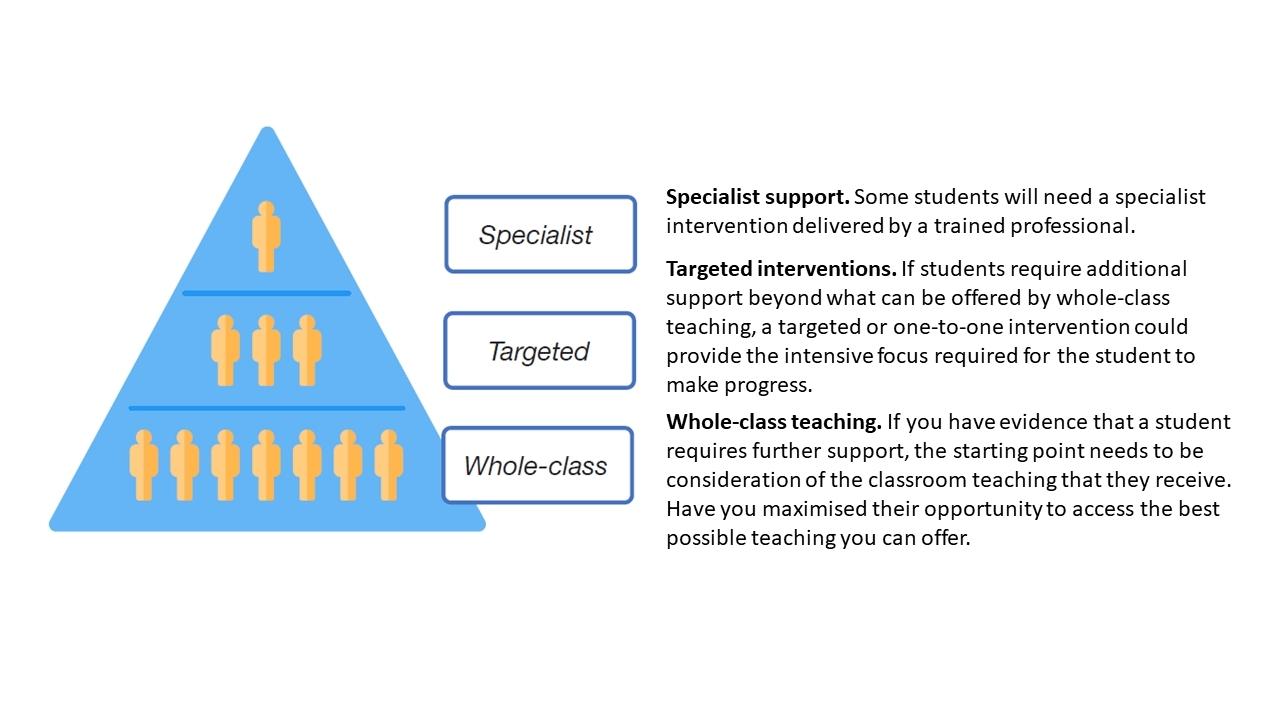

Schools have long been implementing targeted interventions to provide specialised supports for students who may have reading difficulties, for example, students who have a language background other than English. Insights from Response to Intervention (or tiered instruction) can offer guidance on how tutoring sessions can be woven within a school improvement framework.

In a Response to Intervention (RTI) framework, Tier 1 is instruction intended for all students, supplemental and increasingly individualised Tier 2 and then Tier 3 interventions provide additional and more intense support for students who have not achieved expected learning from the general Tier 1 instruction (Davies & Henderson, 2020).

Figure 1: Response to Intervention – Three-tiered model, adapted from (Davies & Henderson, 2020).

For example, an effective small-group reading program Lexia Core5 Reading requires teachers to use assessments to plan, monitor and adjust instruction and activities to nudge students from a Tier 3 intervention that would require highly specialised supports (e.g., special education) (Macaruso & Rodman, 2011).

This requires close attention to how classroom teachers, Teaching Assistants and external partners such as parents and carers, health professionals and community services, can collaborate to provide both wellbeing and academic support (Evidence for Learning, 2020c).

5. Tutoring sessions need to be sustained, regular and adaptive to students’ progress

Tutoring programs can vary widely in terms of duration, frequency and length (lasting weeks, months or years), but programs that work are intensive and sustained rather than once a week or exclusively after school. Regular sessions at least three times a week, or 50 hours over four months, delivered in about 30 to 60 minutes each time appear optimal (Nickow et al., 2020). Low dosage tutoring or afterschool study sessions do not have the same impact as high dosage tutoring – defined as four or more days per week or for about 50 hours over a semester (Fryer, 2017).

Intensive and extended dosage intensifies instruction and students have more time to build demonstrable progress. However, quality of learning and fidelity of delivery is critical to ensure sustained attendance rates.

Adapting to students’ learning progress is critical. Schools could consider ‘dosage’ based on learning levels and progress. For example, a ‘double dose’ in the form of one-on-one tutoring could be provided for struggling students in addition to small-group tutoring. Rather than more of the same, one-on-one instruction could mean re-teaching skills with added practise with more individualised attention and support. Some tutoring interventions are designed to release students from the program earlier if they have attained the outcomes of the program (Nickow et al., 2020).

Implement consistently and evaluate as it is implemented

Beyond the simple conclusion that tutoring works, not all tutoring programs are as effective and effects vary by program characteristics and intervention contexts (Nickow et al., 2020). In recent research, many of the tutoring programs were largely implemented and tested overseas (mostly in the US and UK), and it is important to recognise that we don’t yet know what works and how in the Australian context.

Regardless of the quality of the plan or approach, successful implementation that sees benefits on student learning are well-designed and delivered programs that emphasise fidelity and consistency (Ho, 2019). To track fidelity, tutoring programs should have quality-control parameters in place to monitor the progress of the initiative on teaching quality, student learning, learning engagement and attendance.

Evidence for Learning’s School’s Guide for Supporting Planning and Recovery and the School’s Guide to Implementation describe principles that should be applied for effective implementation of tutoring programs as part of school planning in 2021.

References

Abrami, P. C., Lysenko, L., & Borokhovski, E. (2020). The effects of ABRACADABRA on reading outcomes: An updated meta‐analysis and landscape review of applied field research. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(3), 260-279. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jcal.12417

Baye, A., Lake, C., Inns, A., & Slavin, R. (2017). Effective reading programs for secondary students. Manuscript submitted for publication. Also see Baye, A., Lake, C., Inns, A. & Slavin, R. E. (2017, August). Effective Reading Programs for Secondary Students. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, Center for Research and Reform in Education.

Davies, K., & Henderson, P. (2020). Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools: Guidance Report. Education Endowment Foundation. Retrieved from https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Send/EEF_Special_Educational_Needs_in_Mainstream_Schools_Guidance_Report.pdf

Education Endowment Foundation. (2020). Abracadabra (ABRA). https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/projects-and-evaluation/projects/abracadabra-abra-pilot/

Evidence for Learning. (2020a). One to one tuition. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/the-toolkits/the-teaching-and-learning-toolkit/all-approaches/one-to-one-tuition/

Evidence for Learning. (2020b). Small group tuition. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/the-toolkits/the-teaching-and-learning-toolkit/all-approaches/small-group-tuition/

Evidence for Learning. (2020c). School’s Guide for Supporting Planning and Recovery: A stepped approach for 2021. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/assets/references/E4L-Guide-to-Supporting-School-Planning-and-Recovery-1.0.pdf/

Fryer, R G., Howard-Noveck, M. (2017). High-dosage tutoring and reading achievement: Evidence from New York City. Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/fryer/files/nyc_tutoring13_with_tables.pdf

Ho, P., Vaughan, T., & Deeble, M. (2020). Using technology to support vulnerable students’ learning: An evidence review of system-school interventions for remote learning and transition back to school in response to COVID-19. Unpublished.

Ho, P. (2019, November 29). Unlocking education’s implementation blackbox. Evidence for Learning. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/news/unlocking-educations-implementation-black-box/

Inns, A., Lake, C., & Slavin, R. (2019). A Quantitative Synthesis of Research on Programs for Struggling Readers in Elementary Schools. Best Evidence Encyclopedia (BEE). Available at http://www.bestevidence.org/word/strug_read_April_2019_full.pdf/

Inns, A., Lake, C., Pellegrini, M., & Slavin, R. (2018). Effective programs for struggling readers: A best-evidence synthesis. In Annual meeting of the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, Washington, DC.

Kaffenberger, M. (2020). Modeling the Long-Run Learning Impact of the COVID-19 Learning Shock: Actions to (More Than) Mitigate Loss. RISE Insight. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-RI_2020/017

Macaruso, P., & Rodman, A. (2011). Efficacy of computer-assisted instruction for the development of early literacy skills in young children. Reading Psychology, 32(2), 172-196.

Nickow, A., Oreopoulos, P., & Quan, P. (2020) The Impressive Effects of Tutoring on PreK-12 Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence. EdWorking Paper No. 20-267. Retrieved from https://edworkingpapers.org/sites/default/files/ai20-267.pdf

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students' Well-Being, PISA. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273856-en

Pellegrini, M., Lake, C., Inns, A., & Slavin, R. E. (2018, October). Effective programs in elementary mathematics: A best-evidence synthesis. In Annual meeting of the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, Washington, DC.

Pensiero, N., & Green, F. (2017). Out-of-school-time study programmes: do they work? Oxford Review of Education, 43(1), 127-147.

Sonnemann, J., & Goss, P. (2020). COVID catch-up: helping disadvantaged students close the equity gap. Grattan Institute

How will you determine which students will best benefit from the additional support?

How will you prepare tutors and teachers to implement and support tutoring in your school? What will this look like in your context?

How will you plan for the most effective use of tutors at your school? What are the resources and ‘active ingredients’ that are needed to implement it effectively?