In Australia and worldwide, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted education systems through school closures, transitions to online home-based learning, and major changes to the daily routines of students and school staff.

Using data from 174 countries, the World Bank estimated that students have lost up to one year of basic schooling as a result of school closures (Azevedo et al., 2021). Other negative effects of school closures include drop-out and a reduction in lifetime earning potential, with the total economic loss estimated to be 10 trillion USD. School closures are also projected to have substantial and permanent effects on young people’s welfare (Fuchs-Schündeln et al., 2020).

It is well documented that schools provide a significant degree of mental health and wellbeing support to young people. Australian (Lawrence et al., 2015) and US (Duong et al., 2021) research has indicated that mental health service utilisation in schools is now close to or equivalent to traditional healthcare settings.

Educators are well placed to recognise emerging mental illness in young people by noticing the behavioural, social, and emotional changes that often manifest in the classroom and peer interactions. Educators employ a range of strategies to manage student wellbeing, but the impact of COVID-19 on their approach to this is not yet fully understood.

A recent investigation by the Black Dog Institute examined the impact of COVID-19 and the 2020 lockdown on New South Wales secondary school educators’ approaches to student mental health. A total of 295 educators working in roles directly responsible for student wellbeing (for example, Year Advisors, Heads of Wellbeing or equivalent) were asked if they had reached out to students about their mental health in a different way due to COVID-19. Educators were also asked whether they had implemented a mental health service, program or educational initiative in response to the pandemic.

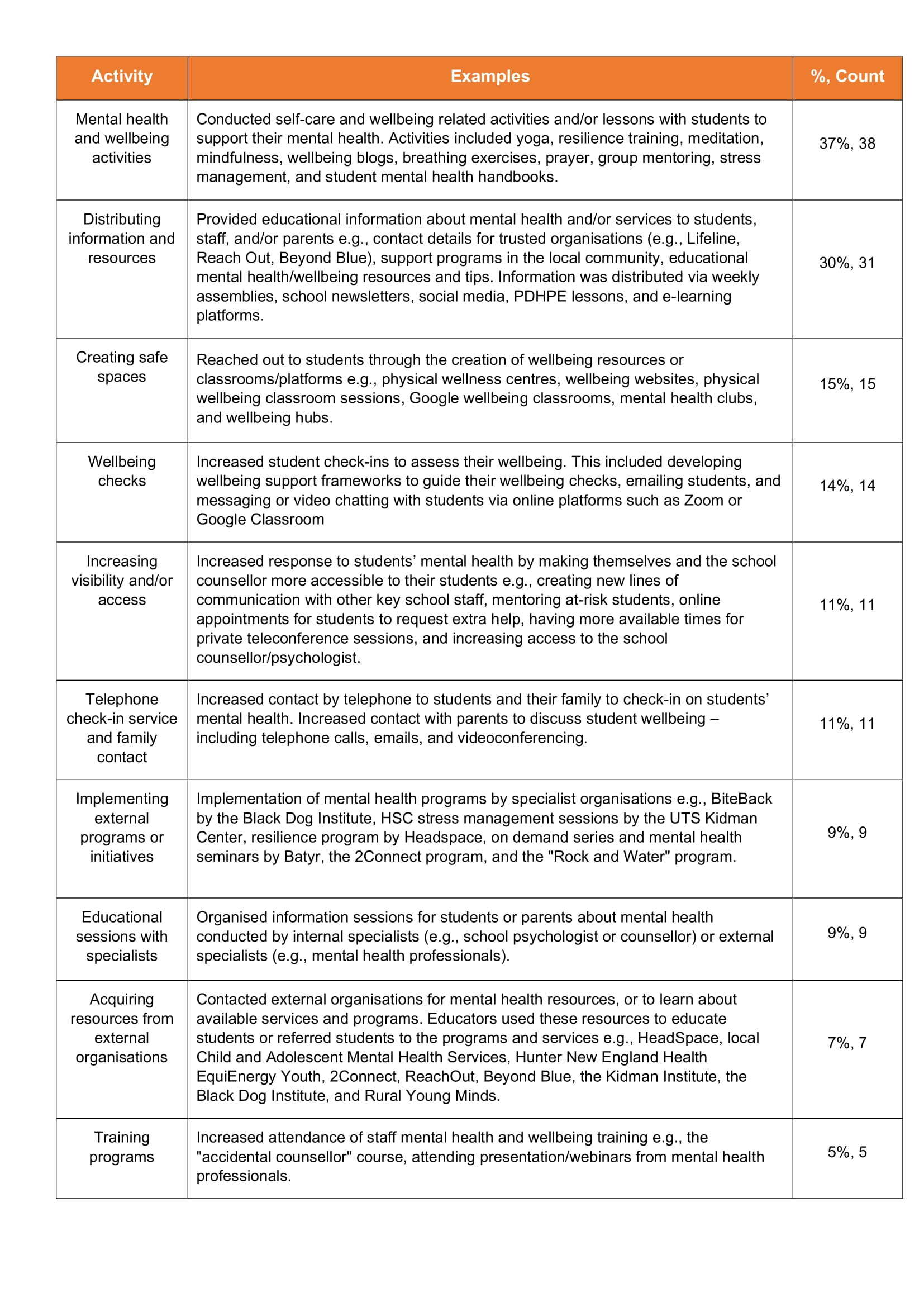

Unsurprisingly, almost three-quarters of survey participants (76 per cent) reported that they had reached out to their students about mental health in a different way due to COVID-19. Just over half of the respondents (51 per cent) had ‘frequently’ or ‘occasionally’ used their school’s e-learning platform (for example, Google classrooms, video-conferencing software) or email to contact students about their mental health. Around one-third (35 per cent) had implemented a mental health service, program or educational initiative. These are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Service, program, or educational information sessions implemented for student mental health due to COVID-19 (N=102)

Just over 1 in 4 educators (28 per cent) reported that they had responded in a way not outlined in the above table. For example, some educators reported that they conducted socially distanced home visits, sent pre-recorded staff messages to students via video, relaxed deadlines on school work, implemented group mentoring programs, established special interest groups among students, and conducted brief parent surveys on child wellbeing.

This investigation is one of the first to provide Australian data on school and educator approaches to student wellbeing in response to COVID-19. It provides evidence that many educators responsible for student wellbeing adapted their approach because of the pandemic, but not all reached out to their students differently. The impacts of these disparities within and across secondary schools are unknown.

While understanding the impact of COVID-19 on learning outcomes is paramount, so too is developing our understanding of how the pandemic has impacted the relationships between students, their teachers and schools – particularly in relation to student wellbeing and mental health. These insights are integral for future-proofing schools, staff and students against the impacts of disrupted learning caused by major events.

References

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Geven, K., & Iqbal, S. A. (2021). Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. The World Bank Research Observer, 36(1), 1-40. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkab003

Duong, M. T., Bruns, E. J., Lee, K., Cox, S., Coifman, J., Mayworm, A., & Lyon, A. R. (2021). Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 48(3), 420-439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9

Fuchs-Schündeln, N., Krueger, D., Ludwig, A., & Popova, I. (2020). The long-term distributional and welfare effects of Covid-19 school closures (No. w27773). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w27773

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven de Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Australian Government, Department of Health. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/11/the-mental-health-of-children-and-adolescents_0.pdf (PDF, 1.9MB)

Thinking about your own school context: What approaches do you use to reach out to students about their mental health? Have the pandemic restrictions impacted any of these strategies? Looking at the table of responses given by educators in this study, are there any approaches that would prove a useful addition to those you are already using?