As a teacher or school leader, what are the mental health needs of your students? How do you promote mental health and wellbeing? What would a whole-school approach look like in your own context? In our latest reader submission, Educational and Developmental Psychologist Dr Jane Kirkham shares details of the ‘Wellbeing Tree’ – an organisational tool created to support educators in addressing whole-school wellbeing.

The importance of fostering student wellbeing and mental health is increasingly becoming an imperative in Australian schools. National mental health and wellbeing data show a 47% increase in the prevalence of mental health disorders in 16- to 24-year-olds over the last 15 years (ABS, 2008 & 2023). Hence, it is not surprising that helping young people to acquire the skills to cope with life’s hurdles is fast becoming a community priority (Quinlan & Hone, 2020).

As Dr Donna Cross and Dr Leanne Lester (2023) note, ‘For many schools, approaches to address wellbeing are haphazard, ad hoc and opportunistic ...’ (p. 205). This would suggest that there is a need for schools to be supported in addressing student wellbeing in a strategic and systematic way – a process often referred to as a ‘whole-school approach to wellbeing’.

In essence, this approach represents a set of planned and coordinated school-wide processes that involve members of the school community working together to create a mentally healthy school (Runions et al., 2021). The challenge for schools, however, is how to capture, connect, and communicate these processes as reflective of the unique context of each school environment.

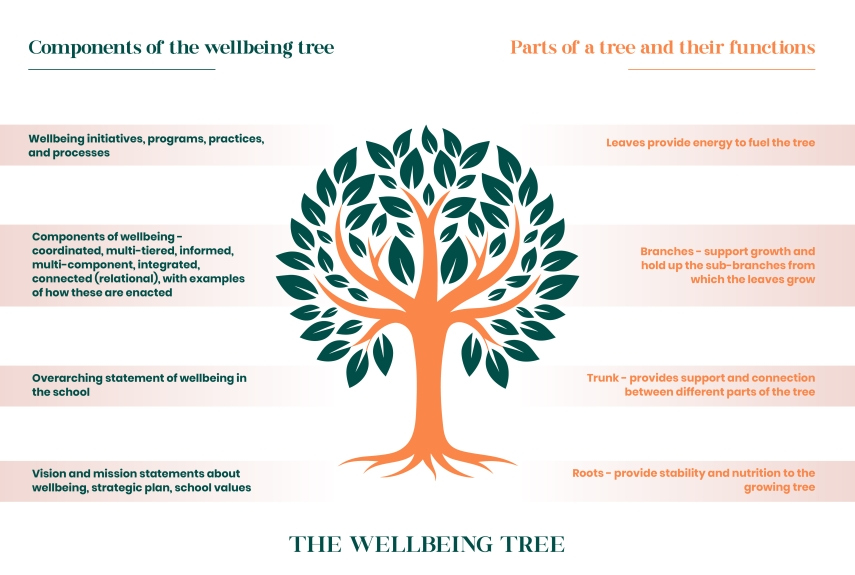

As part of a 2-year Association of Independent Schools of Western Australia (AISWA) pilot project to support educators in addressing whole-school wellbeing, I developed an organisational tool called the ‘Wellbeing Tree’ (Kirkham, 2023) that can be adapted to any school context. This tool was utilised by Wellbeing Coordinators from 10 schools taking part in this pilot project as a visual reminder of the key components of a whole-school approach to wellbeing, as a framework for wellbeing processes and practices, and as a structural guide for school wellbeing plans.

Encapsulating a whole-school approach to wellbeing in the form of a tree has appeal in that, as trees are living organisms of connected elements (such as roots and branches), schools are living communities that consist of complex, interrelated elements that influence the capacity for students to grow and thrive.

This visual representation assists educators in understanding whole-school wellbeing in their specific context.

The roots represent the aims, beliefs, and purpose of the school as revealed in vision and mission statements, strategic plans, school values, and school philosophy. Such statements of aspiration guide decision-making and provide a basis for action. Representing these statements of bigger purpose as roots of a tree emphasises their role of both anchoring the school to core business, and of nourishing the school by directing policies and practices. As schools are increasingly prioritising wellbeing in guiding statements (Allen et al., 2017), it follows that wellbeing practices and initiatives are more likely to become embedded into a strategic and sustainable approach if they are directly linked to school aspirations and priorities.

This link between school purpose and practice is illustrated in the Wellbeing Tree as the trunk. The role of a trunk is to connect roots with branches and leaves and to provide stability. In the Wellbeing Tree, the trunk signifies an overarching statement to describe the unique school perspective on wellbeing and the practices and initiatives employed to promote positive student mental health wellbeing. Essentially, the trunk is a succinct statement of the why, the what, and the how of wellbeing promotion necessary to create a focused and effective approach.

Performing the essential function of providing structure from which leaves can grow to feed the tree, similarly the branches represent a framework that serves to gather initiatives and actions associated with key components of wellbeing promotion. This may be derived from an existing framework or developed by each school as appropriate for their own context.

An additional approach is to utilise 6 branches based on wellbeing research and existing frameworks to create an action-oriented approach to planning. These branches reflect a whole-school approach to wellbeing as being coordinated, multi-tiered, informed, multi-component, integrated, and connected.

Each branch collects initiatives and actions carried out to foster school wellbeing in the form of leaves. In this way the tree analogy emphasises the importance of ‘attaching’ initiatives to a clear practical purpose within a planned organisational structure. To expand on each of the 6 branches further:

Coordinated. Effective and visible leadership to organise, coordinate, and systematise an effective whole-school approach to wellbeing is essential. The role of principals in creating a positive, inclusive, safe and accepting school climate is well documented (Cross & Lester, 2023); the action of coordination also includes a dedicated wellbeing team to drive day-to-day implementation and practices. To be successful, schools will need to consider what needs to be done to support key school personnel in this work.

Multi-tiered. If an approach to wellbeing is to be truly ‘whole school’ it needs to reflect practices that promote wellbeing for all students (Tier 1), as well as actions to support students at risk of developing mental health concerns (Tier 2) and those already experiencing poor wellbeing (Tier 3), (Runions & Cross, 2022). In the Wellbeing Tree tool, examples of initiatives and practices to effectively deliver both proactive and reactive responses to differing student wellbeing needs are captured in relation to each tier.

Informed. Reliable and valid information on which to base decision-making is vital. Programs and procedures with a strong evidence base are more likely to be effective (Runions et al., 2021). Students are also a source of valuable information, assisting in setting priorities. Staff too have an important role in providing information on the effectiveness of practices in their own schools.

Multi-component. Initiatives that include school, family, and community partnerships are more likely to be successful (Mertens et al., 2020). This means not only how other members of the school community can support students, but how the wellbeing of parents and staff can also be considered. For example, attached to this branch are actions to address and promote staff wellbeing – a factor found to be highly influential on student wellbeing.

Integrated. Wellbeing practices are likely to be meaningful if they are aligned and integrated with existing school policies and procedures (Powell & Graham, 2017), such as a bullying policy. In addition, a cohesive approach to student wellbeing considers the developmental and cultural needs of groups within the student body and incorporates practices in line with these needs, such as trauma-informed practices.

Connected. Feeling connected to school through affirming relationships with others is a cornerstone of individual wellbeing, which is why it is important that schools act intentionally and strategically to promote positive connections between students, staff and others both inside and outside the classroom (Kern et al., 2024). This branch refers to the many opportunities for students to relate positively with each other and with staff, such as co-curricular activities and camps.

The Wellbeing Tree tool illustrates an accessible way for schools to conceptualise an action-oriented, strength-based, and practical whole-school approach to wellbeing. By adopting a holistic approach that presents a ‘bigger picture’ of whole-school wellbeing in context, it may be possible for schools to deliver a coordinated, effective, and sustainable process for facilitating the growth of positive mental health.

References

Allen, K.-A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Waters, L. (2017). School Values: A Comparison of Academic Motivation, Mental Health Promotion, and School Belonging With Student Achievement. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 34(1), 31–47. doi:10.1017/edp.2017.5 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/educational-and-developmental-psychologist/article/school-values-a-comparison-of-academic-motivation-mental-health-promotion-and-school-belonging-with-student-achievement/68949CBB1799EB2DDD9336D83974CA69

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2008, October 23). National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/2007

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2023, October 10). National survey of mental health and wellbeing (2020-2022). https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/2020-2022

Cross, D., & Lester, L. (2023). Leading improvement in school community wellbeing. ACER Press.

Kirkham, J. (2023). Envisaging a whole-school approach to wellbeing: The “wellbeing tree.” Education Research and Perspectives, 50, 1–35. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.T2024042000006001503715637

Kern, M. L., Arguís-Rey, R., Chaves, C., White, M. A., & Zhao, M. Y. (2024). Developing guidelines for program design, practice, and research toward a positive and well-being education practice. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2024.2352743

Mertens, E., Deković, M., Leijten, P., Van Londen, M., & Reitz, E. (2020). Components of school-based interventions stimulating students’ intrapersonal and interpersonal domains: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(4), 605-631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00328-y

Powell, M. A., & Graham, A. (2017). Wellbeing in schools: Examining the policy–practice nexus. The Australian Educational Researcher, 44, 213-231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-016-0222-7

Quinlan, D. M., & Hone, L.C. (2020). The educators’ guide to whole-school wellbeing: A practical guide to getting started, best-practice process and effective implementation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429280696

Runions, K. C., Pearce, N., & Cross, D. (2021). How can schools support whole-school wellbeing? A review of the research. Report prepared for the Association of Independent Schools of New South Wales. https://www.aisnsw.edu.au/Resources/WAL%204%20%5BOpen%20Access%5D/AISNSW%20Wellbeing%20Literature%20Review.pdf

Runions, K, C., & Cross, D. (2022). Student and staff wellbeing and mental health. Report Commissioned by Independent Schools Australia. https://isa.edu.au/documents/report-wellbeing-of-students-and-staff/

As a teacher or school leader, what are the mental health needs of your students?

When was the last time you reviewed your own policies and practices in relation to student mental health wellbeing?

How do these policies and practices link to your school aspirations and priorities?