How can schools best work with parents, carers, grandparents and older siblings to support students and improve their learning? Dr Tanya Vaughan and Susannah Schoeffel explore two evidence-based recommendations from a new guidance report for Australian practitioners, and share practical examples of action.

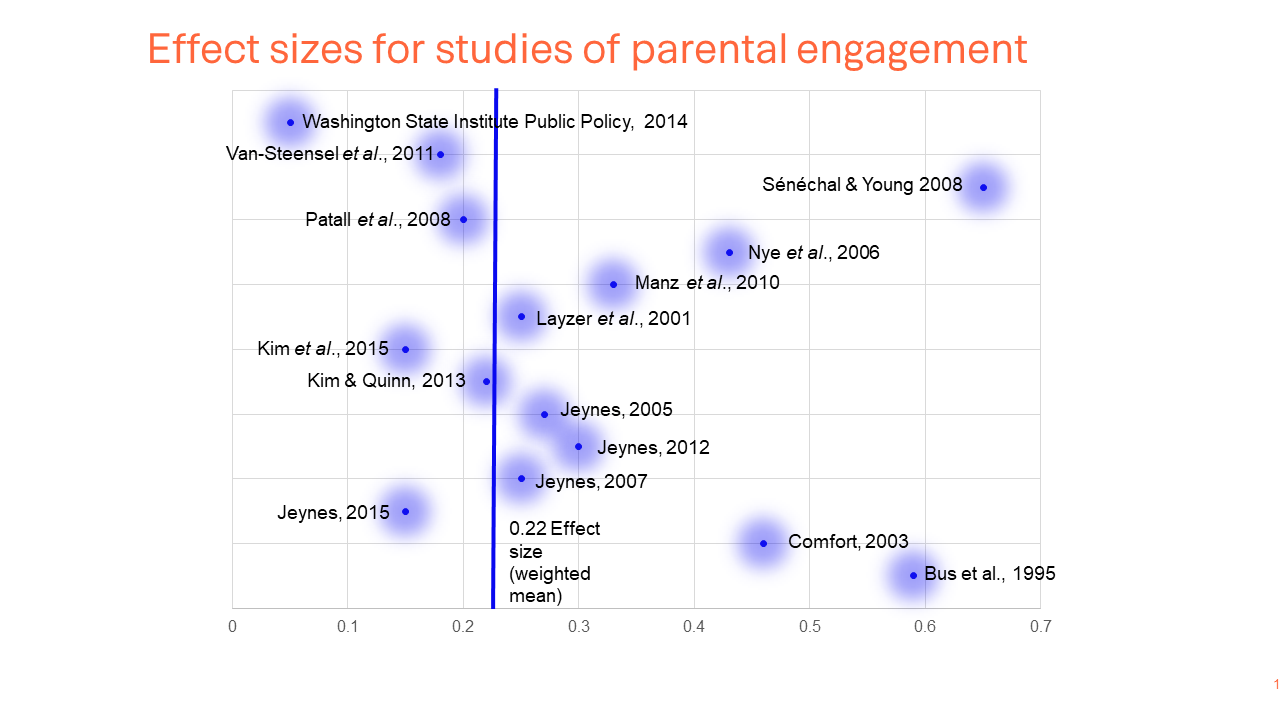

Engaging parents in the learning of their children can improve students' learning by an average of three months (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019b), as seen in Figure 1.

Parental engagement is defined as activity that supports children's learning at home, at school and in the community. This is distinct from parental involvement, which is focused on parents attending events or volunteering (Australian Government Department of Education and Training, 2019).

In this article, parents are defined as those that have significant responsibilities for children – including parents, carers, grandparents and older siblings.

Evidence-based recommendations

Drawing on learnings from the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), Evidence for Learning (E4L) are developing a range of Guidance Reports, contextualised for Australian practitioners. Written primarily for school leadership teams, the next guidance report will be released in late October and will explore how best to work with parents to support children.

The Guidance Report presents four evidence-based recommendations that outline how parents can be engaged with schools to have the best chance to improve students' learning. These are:

- Critically review how you work with parents;

- Provide practical strategies to support learning at home;

- Tailor school communications to encourage positive dialogue about learning; and,

- Offer more sustained and intentional support where needed.

This article will focus on the areas of learning at home and communication.

Provide practical strategies to support learning at home

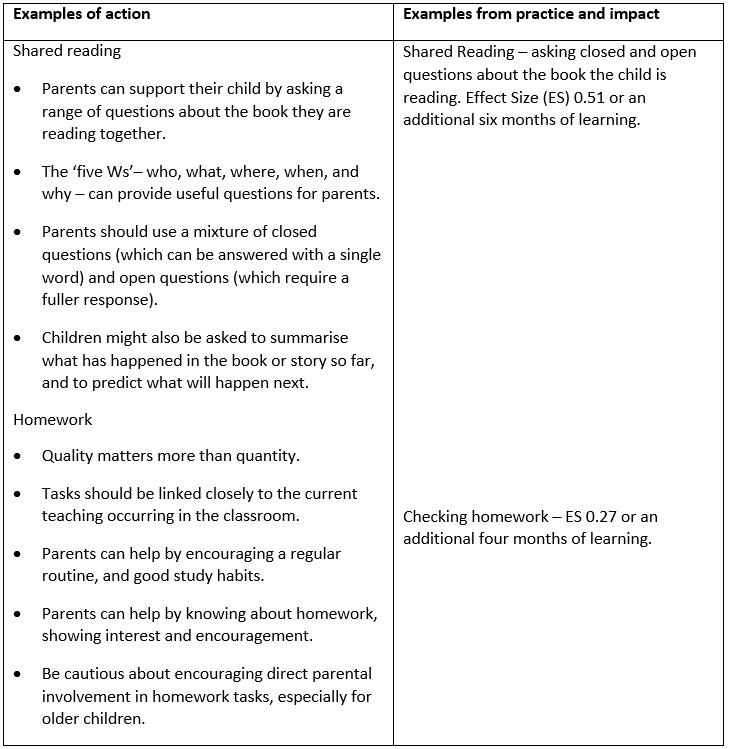

The strategies for parental engagement are different for different age groups. While the overall evidence on parental engagement in learning is mixed, there is better evidence that particular skills are important for children to develop at different ages and stages, so it makes sense to target those. Shared reading is effective for younger children, while for older children helping them in managing homework is a key parental role.

For supporting parents of younger children, encouraging the development of shared reading practices at home is an effective way to improve students' literacy skills (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019b). Parents asking open and closed questions about the book the child is reading is more effective than parents listening to their child read

Shared reading is explored in greater detail in Table 1. In Queensland, a literacy and arts-based program, that was implemented in eight schools, showed statistically significant increases at the regional schools (three schools) in attendance, English grades and literacy outcomes as measured by the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) (Vaughan & Caldwell, 2017).

Children who regularly complete their homework have higher achievement than those who do not (Van Poortvliet, Axford, & Lloyd, 2018). The impact of homework on students' learning outcomes varies dependent on age. Homework in the secondary setting has been seen to exert a stronger influence on student's learning that within the primary setting (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019a).

Table 1: Examples and measurements of impact for supporting learning at home. Adapted from (Van Poortvliet, Axford, & Lloyd, 2018, p. 7; Jeynes, 2012; Vaughan, 2019).

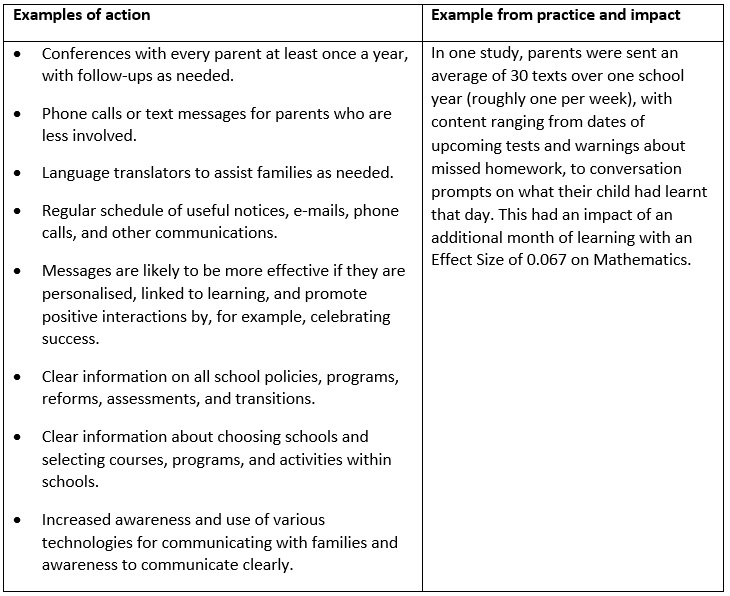

Developing and maintaining communication with parents

Personalised school communications can improve children's learning and attendance. It's important that the communication to parents flows in two ways, so that they both receive and provide meaningful communication, from and to the school. Messages and letters are more effective “if they are personalised, linked to learning and promote positive interactions by, for example, celebrating success” ( van Poortvliet, Axford, & Lloyd, 2018, p. 7). Table 2 outlines examples of communication to parents.

Table 2: Examples and measurements of impact for communications to encourage positive dialogue about learning. Adapted from

Parental engagement can be an effective way to improve students' learning and attendance. The best ways that parents' can support their children, changes as a child grows. Literacy activities such as shared reading is effective at a young age, while for older students the setting of routines and providing encouragement for homework is helpful. The use of personalised communication can improve children's learning outcomes.

Considerations for teachers and leaders include: are the parents of your students ready to engage in this way? Have you considered what is required to establish trust with your school (how do you get them through the gate)?

References

Australian Government Department of Education and Training. (2019). Parent Engagement in Learning. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.au/parent-engagement-learning-1

Van Poortvliet, M., Axford, N., & Lloyd, J. J. (2018). Working with Parents to Support Children's Learning: Guidance Report. London: Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/ParentalEngagement/EEF_Parental_Engagement_Guidance_Report.pdf

Education Endowment Foundation. (2019a). Evidence for Learning Early Childhood Education Toolkit: Education Endowment Foundation. Viewed 1 October 2019 https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/the-toolkits/the-teaching-and-learning-toolkit/

Education Endowment Foundation. (2019b). Evidence for Learning Teaching & Learning Toolkit: Education Endowment Foundation. Parental Engagement. Viewed 1 October, 2019 https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/toolkit/parental-engagement/

Emerson, L., Fear, J., Fox, S., & Sanders, E. (2012). Parental engagement in learning and schooling: Lessons from research. A report by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY) for the Family–School and Community Partnerships Bureau: Canberra.

Jeynes, W. (2012). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban education, 47(4), 706-742.

Miller, S., Davison, J., Yohanis, J., Sloan, S., Gildea, A., & Thurston, A. (2016). Texting Parents: Evaluation Report and Executive Summary. Education Endowment Foundation. Viewed 1 October, 2019 https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Projects/Evaluation_Reports/Texting_Parents.pdf

Sénéchal, M. (2006). The effect of family literacy interventions on children's acquisition of reading. Retrieved from New Hampshire, USA: https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/lit_interventions.pdf

Sénéchal, M., & Young, L. (2008). The effect of family literacy interventions on children's acquisition of reading from kindergarten to grade 3: A meta-analytic review. Review of educational research, 78(4), 880-907.

Vaughan, T. (2019). Building Parental Engagement. Resources in Action, Management in Action, 10.

Vaughan, T., & Caldwell, B. J. (2017). Impact of the creative arts indigenous parental engagement (CAIPE) program. australian art education, 38(1), 76-92.

As a school leader, are there structures in your school that support teachers to engage parents in a constructive way (through student-led conferences, or digital platforms)?

As a teacher, how can you enable parents to support student learning? What do they need to know, relevant to their child’s age and development?