As educators in Australia return to face-to-face teaching, and schools around the world grapple with new ways of working to provide continuing support to students during the pandemic restrictions, readers have been getting in touch to tell us what's been happening in their own context. This week, Teacher is sharing some of those stories. This final instalment is written by Michael Rosenbrock – Assistant Principal at Wodonga Senior Secondary College, in regional Victoria on the Murray River border with New South Wales.

The start of the school year for 2020 was different. With the smell and eerie light of bushfire smoke still lingering, staff and students returned to school tired after a long summer. Whilst only a small number of our school community had been directly impacted by the bushfires, the indirect impact was clearly felt by all. Feedback from staff and students clearly indicated that returning to school was a positive: providing a different focal point; the reassurance of familiarity and routine; a sense of community; and specific supports for individuals as required.

Fast forward to the home stretch of Term 1 and the impacts of summer were rapidly pushed to the back of our minds as we contemplated what the pandemic might mean for our school community. Wodonga Senior Secondary College (WSSC) is located in the large Victorian regional town of Wodonga. With a student population of approximately 850, the College provides a broad program catering to diverse student aspirations and pathways, with our motto ‘Every Student, Every Opportunity, Success for All' encapsulating the WSSC ethos. Socioeconomic disadvantage impacts significantly upon our cohort, with this further compounded by our regional location, several hours' drive from Melbourne.

Initial response

The early response to the pandemic was focused at the leadership level of the College. An expanded College Executive group was formed early on and met daily to plan and prepare. This proactive work set strong foundations for the months ahead.

We quickly got a preview of the pace of change. Athletics sports cancelled with only a few days to go. Parent-teacher night moved from face-to-face to online and rolled out within less than a week. Engagement with and feedback from the online parent-teacher night was great, providing some valuable positive momentum during uncertain times.

Technological readiness

An early and urgent priority within my focus area of Curriculum was to work closely with our Information Technology team on viable solutions for transitioning rapidly to remote learning. WSSC is fortunate to have an experienced and well-resourced IT team, whom I cannot thank and praise enough for their efforts.

On the Learning Management side, we were very fortunate to have prioritised online curriculum documentation since WSSC's inception, using our bespoke system called SIMS. Staff and students had a high level of familiarity with the system, and further improvements to its functionality and use had been a high priority over recent years.

Less clear cut was the best approach to take to online lesson delivery and communication with students. We rapidly explored a range of platforms, evaluating them in terms of their functionality, usability, privacy, security, administration and roll-out. In this work I was very appreciative to have a background in IT before a career change into education. The clear choice for our context was Microsoft Teams, which we already had up and running at the College but were not using school wide. The ability to put in place appropriate security and privacy measures was critical in this decision, which was validated later in the difficulties schools experienced with some other platforms. Furthermore, the ability to make a shift from email to ‘channels' in Teams was seen as a vital step to reduce the communication overload on teachers.

Student access to devices and internet had potential to be a significant barrier for remote learning. The College has a one-to-one laptop program for students, which provided a very strong foundation. The Student Operations team worked with staff to collect information from every student on their level of access to a computer at home and the reliability and quality of internet access at home.

This huge effort provided clear information on the specific students who needed assistance. Initially, this involved making do with any computers that could be repurposed, and internet dongles donated by staff and community. Once the transition to remote learning was confirmed for Term 2, the Victorian Department of Education and Training rolled out computers and internet access devices to fill the gaps we had identified. These steps allowed us to ensure every student had an opportunity to access their learning online.

Online teaching and learning

The other pressing priority was the development of a plan for effective online teaching and learning.

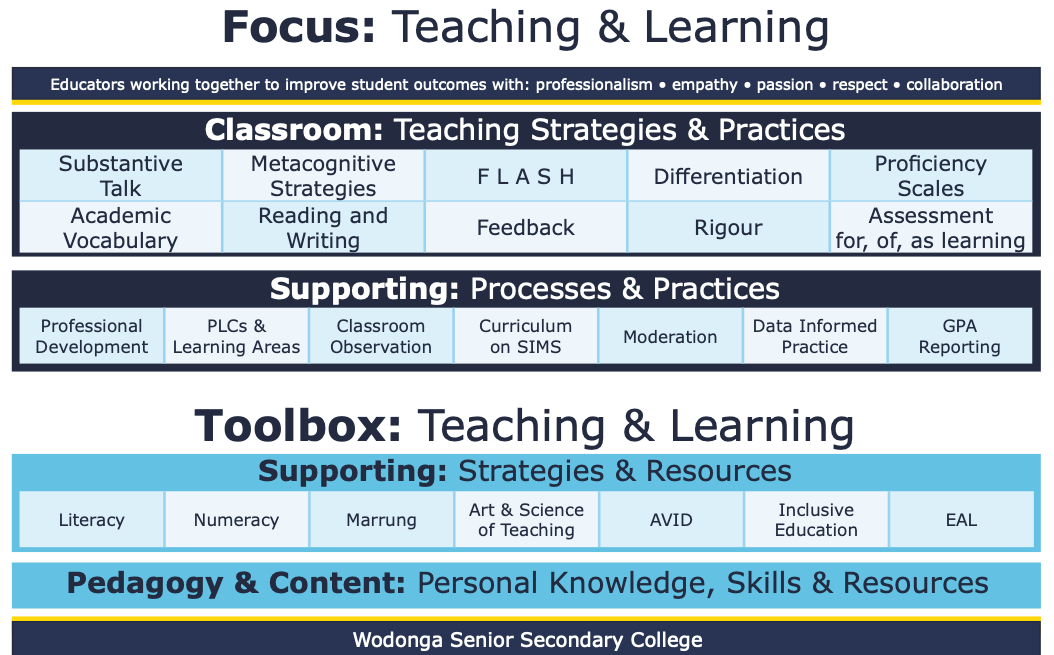

Over recent years, I have led the development of a clear model of teaching and learning practice for WSSC, referred to as the Wodonga Way of Teaching and Learning. This was the starting point for looking at what would need to be adapted for remote learning. Whilst all elements remained relevant, many required adjustment. For example, Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) were refocused on supporting and connecting staff, whilst the use of effective feedback mechanisms was expected to be even more critical in an online environment.

The Wodonga Way of Teaching and Learning, Wodonga Senior Secondary College. Image: supplied.

The next step was consideration of the structure and expectations around online lessons. We delved into lots of reading, research and ideas around online learning, were inspired by the insights of Brene Brown (2020), and considered in depth the possible combinations of asynchronous and synchronous learning time within the week. Regular engagement with students via video was something we concluded was essential, settling on an expectation of direct engagement with each class via video for 15-25 min during each of the three lessons per week on our existing timetable. The remainder of class time was to be used for independent learning, collaboration between students and feedback from teachers. Keeping existing structures, such as the timetable, was seen as important to provide security, familiarity and routine in uncertain times, echoing the positive impact returning to school had after the summer bushfires.

During preparations for remote learning, concerns were expressed by some staff, and within the broader community discourse, that socioeconomic and educational disadvantage would have significant impact on students in online learning, leading to disengagement. In the face of this challenge we made a conscious decision to put our best foot forward, use all available evidence to support our decision making, and place confidence in our students and staff to rise to the challenge.

Online trial day

We planned an online learning trial day for the last Wednesday of Term 1 to identify and respond to any issues. A few days beforehand the Victorian Premier announced the early start of school holidays. We made the call to proceed, even though community perceptions were that holidays had started. Students, parents and carers were informed of the importance of the trial and that classes would run online on the existing timetable.

The trial day was a resounding success! Our IT systems coped with close to 700 external devices online, and student attendance in online classes was excellent. This success provided confidence for all involved in our ability to successfully transition to remote learning and was a strong counter to concerns that students would simply disengage.

Supporting staff

Amongst all of the planning and preparations, providing support to staff was a high priority. Briefings were provided to communicate essential information and get feedback. Staff were surveyed on their professional learning needs for remote learning and an extensive internal program was run on the available pupil free day. Each staff member was linked with someone on the College Executive for regular wellbeing check-ins. Being able to create video meetings via Teams proved invaluable: making running professional development easy; allowing staff to communicate; and supporting everyone to remain connected by ‘seeing' each other via video.

Feedback, tracking and adjustments

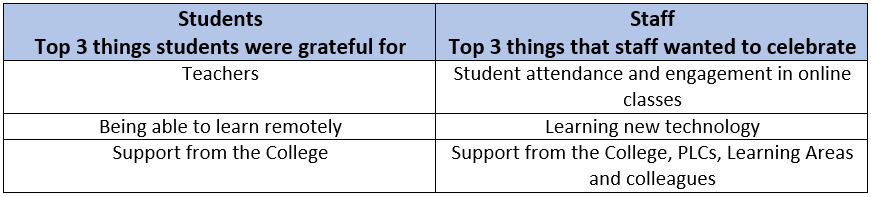

Throughout this journey feedback from staff and students was regularly collected. This identified issues such as insufficient screen break times, which led us to shorten lesson durations throughout the week and strongly encourage everyone to take breaks. It also was a great way to capture successes, such as the feedback below.

Feedback from staff and students, Wodonga Senior Secondary College.

We also tracked and monitored a range of sources of data. Student attendance remained high, exceeding the same time in the previous year, with over 95 per cent of students regularly engaged in remote learning over the duration.

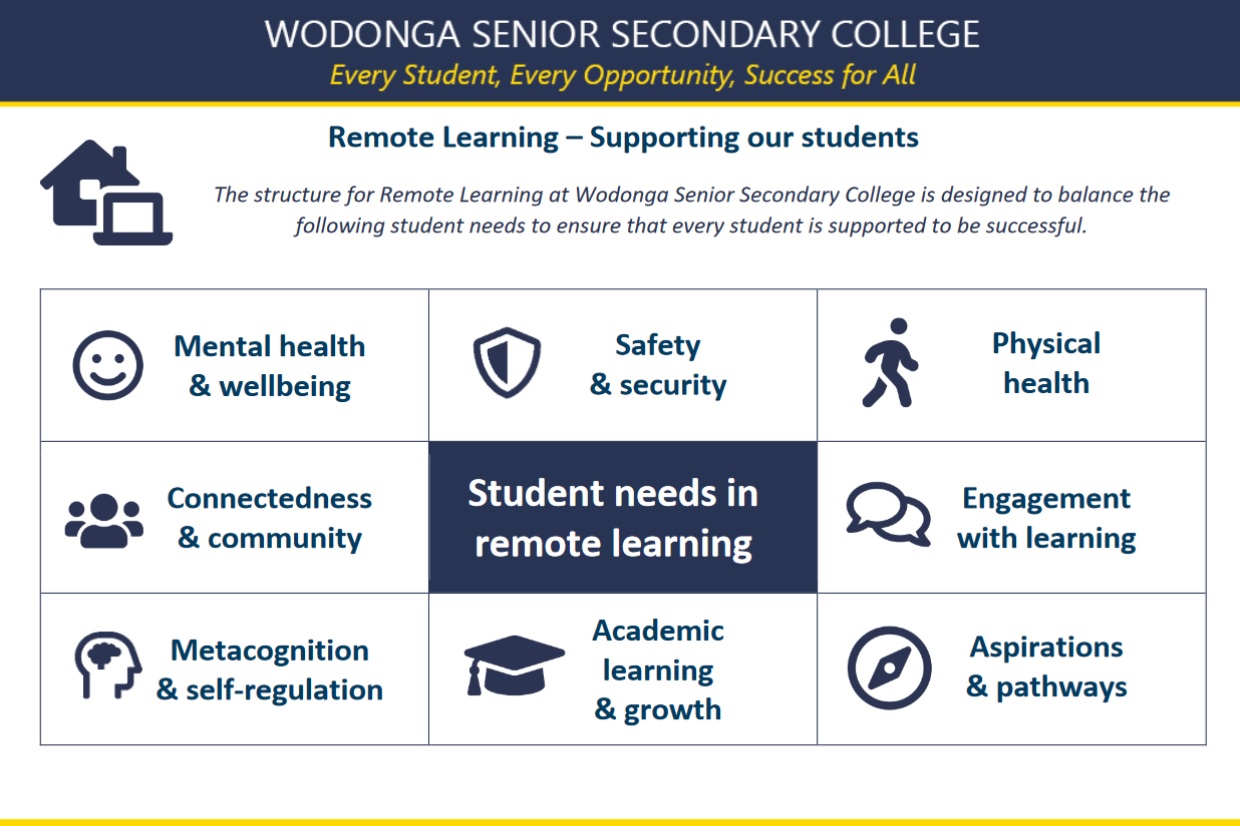

A full picture of student needs

Reflecting upon how we were supporting students in remote learning, it was apparent that we were balancing a lot more than a traditional focus on academic growth. We delved deeper into this notion, widely reading existing research and emerging perspectives, as well as collecting feedback from students, parents and staff. This culminated in the following model of the full picture of student needs in remote learning.

Student needs in remote learning, Wodonga Senior Secondary College. Image: supplied.

At this point, many of these needs were met by what we had put in place, including:

- Our wellbeing team tracking and supporting vulnerable students directly and regularly engaging with our entire cohort using creative online videos;

- Providing routine and consistency in the structures and online learning environment;

- Regular connection between students and teachers via online video classes;

- Comprehensive monitoring of student engagement via House Leaders and Educational Support staff;

- Weekly check-in with students in groups and individually via their Graduate Program class and teacher;

- Pathways staff connecting with parents and students online to continue career conversations;

- Developing a Grade Point Average guide for remote learning to provide clarity on expectations and reporting;

- Student Leadership Council providing break time activities via online video in teams to connect students;

- Maintaining connectedness to Houses and encouraging physical activity via Isolation Olympics challenges.

Based on this work we also took further steps to refine our practice, developing a comprehensive Remote Learning Structure, which included:

- A Health and Wellbeing block of time in the middle of the week for students to refresh and recharge. Scheduled in the afternoon to encourage getting outdoors even in cold weather.

- Specific Independent Learning blocks spread over the week. Providing opportunities for students to take responsibility for their learning and work independently whilst also balancing other roles that they may fulfil at home and take care of themselves.

Student metacognition and self-regulation has been an emerging area of focus at WSSC, and it was this work, along with our engagement in the Partnership for Evidence and Research for Learning Success (PEARLS) program with Evidence for Learning and the Science for Learning Research Centre that informed the introduction of the Independent Learning blocks.

All of our data clearly showed that our cohort, despite high levels of disadvantage, were choosing to engage strongly with learning from home. This next step made visible our trust and belief in our students' ability to take responsibility for their learning by handing over a block of the learning time to them to manage. The initial feedback from this has been very positive, and we are looking at how it can be leveraged to make a longer-term shift in mindset and practices for our school community.

Challenges, successes and next steps

These exceptional times have not been without their challenges. Workload for staff and the learning curve has been exceptional, and the pace of change, whilst managed well, is not sustainable. Practical work was an expected challenge in remote learning, however our staff made great use of technology to innovate and adapt so that their programs could continue. This challenge was most acutely felt by staff and students in Vocational Education and Training subjects, who will need further support for the remainder of the year to ensure they can meet stringent requirements for evidence of competence.

The resilience, determination and capability of teachers has been strongly underscored during this time. As too has the value that students, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds, place on their learning, and their ability to take responsibility for their learning. This experience has also highlighted the central role that schools fulfil in providing a learning community that supports students to meet the full range of their needs. And finally, it has highlighted the critical role of processes, structures and leadership in ensuring success in challenging times.

We are now entering the next step in what has been an epic journey this year. A time for reflection and learning, we are now looking to take some steps back and investigate what the implications of this experience are for our future practice.

References and related reading

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2020). Spotlight – what works in online/distance teaching and learning. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/research/spotlight/what-works-in-online-distance-teaching-and-learning

Brown, B. (2020, March 21). Collective Vulnerability, the FFTs of Online Learning, and the Sacredness of Bored Kids. brenebrown.com https://brenebrown.com/blog/2020/03/21/collective-vulnerability/

California Department of Education. (2020). Lessons from the Field: Remote Learning Guidance. https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/cr/dl/lessonsfrfld.asp

Department of Education and Training, Victoria. (2020). Teaching and remote learning from home. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/Pages/Teachingandremotelearning.aspx

Evidence for Learning. (2020). Remote Learning Evidence Assessment. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/assets/COVID-19-Home-supported-learning/EEF-Remote-Learning-Rapid-Evidence-Assessment-FINAL.pdf

Vaughan, T., & Schoeffel, S. (2019, December 13). Building students' metacognition and self-regulation. Teacher magazine. https://www.teachermagazine.com/articles/building-students-metacognition-and-self-regulation

Michael Rosenbrock says the next part of the journey for his school is reflection and learning. ‘We are now looking to take some steps back and investigate what the implications of this experience are for our future practice.’

As a school leader, have you set aside time for staff to reflect on the past few weeks? What are some of the learnings you’ll take into your future practice?