A different way to organise the school curriculum

There are good reasons to rethink how we organise the school curriculum. An alternative would be to structure the curriculum as a sequence of proficiency levels unrelated to age or year level.

Currently, the school curriculum is packaged into year levels.

For example, a Year 5 teacher is expected to teach the Year 5 curriculum to all Year 5 students who are then assessed and graded against Year 5 curriculum expectations.

The problem with this approach is that, in each year of school, students are at very different points in their learning. The most advanced 10 per cent of students are about five to six years ahead of the least advanced 10 per cent of students.

This means that less advanced students often are presented with year-level material that is much too difficult. For many students, this occurs year after year. Some fall increasingly far behind with each year of school. By 15 years of age, large numbers of these students fail to meet even minimum standards of reading, writing, mathematics and science, and many have essentially disengaged from the schooling process.

At the same time, more advanced students often are presented with year-level material that is much too easy. Many achieve good grades on year-level expectations with minimal effort. These students fail to make the progress and attain the levels of which they are capable. By 15 years of age, the top 10 per cent of Australian 15-year-olds in mathematics perform at about the same level as the top 40 per cent of students in some other countries.

The attempt to specify what an individual should learn on the basis of their age or year level flies in the face of what we know about learning itself. Successful learning is most likely when learners are presented with appropriate levels of challenge. Learning is far less likely when challenges are within students' comfort zones or so far ahead of them that they are unable to engage meaningfully and so become frustrated.

In short, the way we organise the school curriculum (and the way most of the world organises the school curriculum) is not consistent with what we know about the conditions for successful learning. The current curriculum is not designed to guarantee teaching at an appropriate level of challenge for each and every learner.

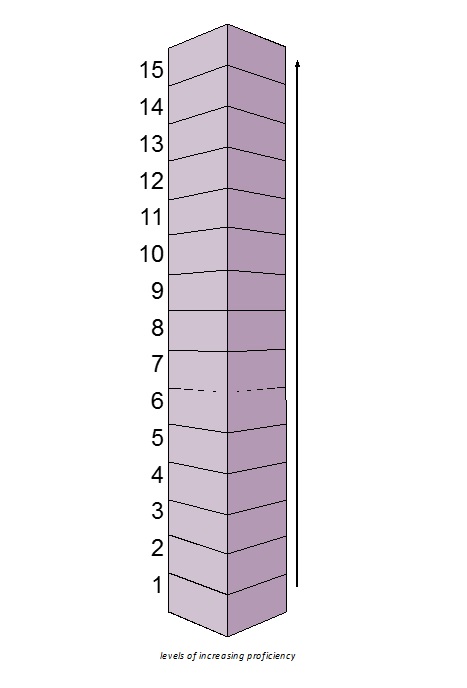

An alternative would be to structure the curriculum not in year levels but in proficiency levels, where a proficiency level is an absolute level of attainment or competence in an area of learning, regardless of age or year of school.

Click here to view an enlarged version of the diagram below.

The reorganisation of the curriculum in this way would be a radical departure from current practice. It would require a change in mindset – a different way of thinking and working for teachers, students and parents. What it means to learn successfully would be defined not in terms of year-level curriculum expectations, but with reference to a hierarchy of proficiency levels through which students would progress throughout their time at school.

Although this way of thinking would be new to the school curriculum, it is a familiar concept in learning areas such as music, second languages, swimming and (Kumon) mathematics, where students progress through a sequence of proficiency levels not linked to ages or years of school.

Advantages

The reorganisation and presentation of the school curriculum as a hierarchy of proficiency levels would have a number of advantages. These advantages include an improved basis for:

- identifying where individuals are in their long-term learning progress

A sequence of proficiency levels provides a frame of reference for identifying and communicating the points individuals have reached in their long-term learning at any given time. This is potentially valuable information for students, teachers and parents. If proficiency levels have the same meaning across schools, year levels and over time, they can be used to identify and report the levels students have reached and to set appropriate goals for further learning. Considered together, proficiency levels make explicit and illustrate the nature of long-term progress in a learning area. - recognising and responding to students' very different levels of attainment in each year of school

When learning is undertaken in relation to a set of proficiency levels, and teachers assess individuals to establish the highest level they have achieved and the level they need to work on next, it is more likely that individual learning needs will be identified and addressed. Currently, accurate information about where individuals are in their long-term progress is often lacking. When teachers interpret their role as delivering the same year-level curriculum to all students in the same year of school, they often overestimate the abilities of less advanced students and underestimate the abilities of more advanced students. - targeting teaching on an individual's current level of proficiency and setting appropriate, personalised learning goals

The value in establishing where students are in their long-term learning is that teaching can be better targeted on current levels of attainment and learning needs. Knowing the level a student has reached makes clearer what they need to work on next. This is likely to be more effective in promoting learning and raising standards in our schools than simply delivering the same year-level curriculum to all students regardless of their levels of attainment. - assessing and reporting student attainment

When the curriculum is organised into proficiency levels, the fundamental purpose of assessment is to establish the proficiency level a student has reached (based on evidence of what they know, understand and can do) and to diagnose obstacles to further progress. In contrast, most current school assessments are focused on establishing how much of the year-level curriculum a student can demonstrate and grading them accordingly - monitoring and reporting growth

A set of proficiency levels provides a basis for monitoring and reporting student growth. Teachers, students and parents are better able to see and appreciate the progress individuals make as they work through a set of proficiency levels over time. In contrast, current school reports generally obscure long-term growth. A student who receives the same or similar grade year after year is given little sense of the absolute progress they are making. - identifying minimum levels of attainment for particular purposes

Proficiency levels also provide a basis for identifying and specifying absolute levels of attainment required for particular purposes – for example, the minimum level of reading required to function effectively in the workplace, or the minimum level of mathematics required for entry into a particular course of study. When minimum levels of proficiency are specified in this way, it is possible to monitor over time a student's progress towards the achievement of these levels. - encouraging and monitoring deep learning

A more explicit focus on long-term progress in an area of learning encourages a greater emphasis on skills, understandings and attributes that develop across the years of school. These include understandings of key concepts and principles, higher-order thinking skills, personal attributes and general capabilities such as problem solving. A sequence of proficiency levels conveys the nature of such long-term learning and development, sometimes referred to as a learning progression. This focus on deep, long-term learning may be less evident in curricula packaged into year levels.

Lifting achievement levels

The approach Australia has adopted to improving student performance is to specify year-level curriculum standards and to hold all teachers and students accountable for achieving those standards. This clearly is not working; there has been a significant decline in the reading and mathematical literacy levels of Australian 15-year-olds since the turn of the millennium. Each year, some 40 000 15-year-olds have reading levels below the OECD's minimum standard for effective functioning in society. More than 57 000 have mathematics levels below this minimum. Most of these students no doubt have struggled with, and fallen below, year-level expectations throughout their schooling.

A common response to these observations is to propose higher year-level expectations. But this misses the point. Because of the wide variability in students' levels of attainment, any single year-level standard, wherever it is set, will be inappropriately easy or unrealistically difficult for a large proportion of students.

It is also sometimes considered ‘equitable' to set the same learning expectations for all students in the same year of school. But there is nothing equitable about expectations that are at an appropriate level of challenge for some students but at an inappropriate level for others. An equitable system would be one in which every student was provided with stretch challenges appropriate to their current level of attainment and in which every student was expected to make excellent progress every year – regardless of their starting point. Such a system also would be more likely to produce a lift in our national performance.

Editor's note: This article was updated on 21 February, 2018 to include the diagram.