Over the last 12 months the importance of metacognitive skills and strategies has come to the fore, in light of the home-supported learning schools enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

In the context of remote learning, it is likely that those students who had already developed metacognitive strategies and skills were better prepared to learn and apply that learning independently.

Metacognition is the process of how learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning (Quigley et al., 2019), and together with cognition and motivation forms the three interconnected pillars that we recognise as self-regulation.

Approaches that focus on the development of metacognition and self-regulation show a strong impact for students of all ages, with an average of an additional seven months of learning across a year (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019a).

The PEARLS project

The Partnership for Evidence and Research for Learning Success (PEARLS) project was developed to build expertise around evidence use in Victorian school leaders and teachers. Supported by The William Buckland Foundation, it included a scholarship for five Victorian schools to engage in a year-long professional learning (PL) program focused on implementing metacognition and self-regulation to improve student outcomes.

Evidence for Learning (E4L) collaborated with the Science of Learning Research Centre, based at the University of Queensland, to provide the up-front PL and ongoing support for each school. As part of the PL, leaders and teachers were supported to design an implementation plan (Sharples et al., 2019), detailing how they would develop metacognition and self-regulation in their learners. This article explores the implementation journey of Wodonga Senior Secondary College, developed and refined as an outcome of the PEARLS project.

Wodonga Senior Secondary College

Wodonga Senior Secondary College (WSSC) is a large regional school catering for 820 students in Years 10-12. More than 75 per cent of WSSC students are from the bottom quarter of socio-educational advantage (SEA) with the school having an Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) of 866 – well below the Australian average of 1000 (ACARA, 2020). In meeting the needs of their diverse cohort of learners, the leadership and staff have explored the evidence behind approaches that are effective in building student capacity and decided to focus their energy on strategies that build metacognition and create self-regulated learners.

A plan for implementation

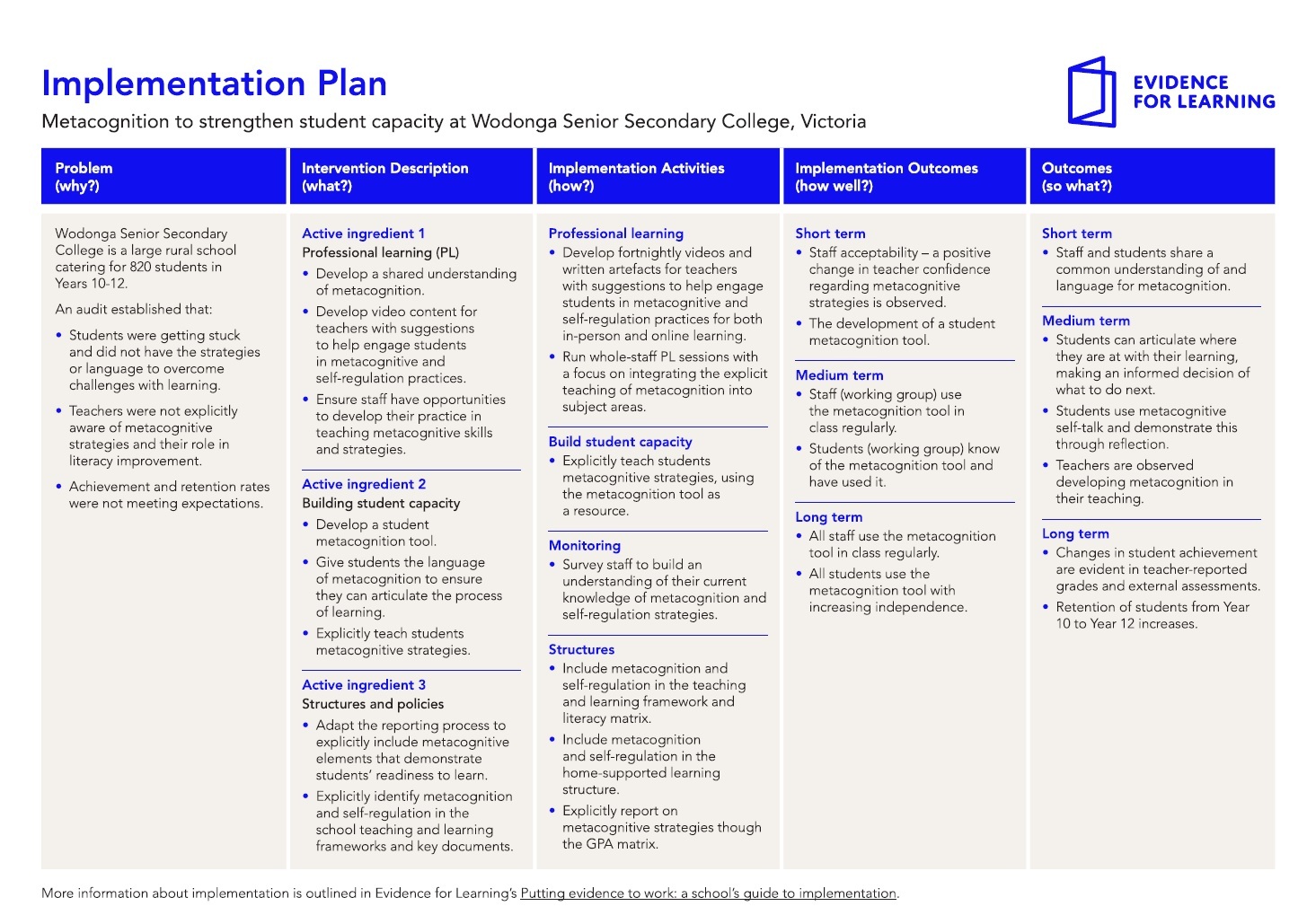

Previous Teacher articles from E4L have explored implementation science, the importance of monitoring and evaluation, and the process of developing an implementation plan to guide the activities that occur at the school level to improve student outcomes (Vaughan & Albers, 2017; Vaughan et al., 2019). Figure 1 outlines the implementation approach developed by WSSC, exemplifying several principles of effective implementation:

- Implementation is a process, not an event, and should be considered as a long-term initiative (two to three years).

- Identifying ‘active ingredients’ – the features of a plan which need to be adopted closely – allowing staff and schools to consider which elements require fidelity, and where flexibility exists (Education Endowment Foundation, 2019b).

- Ensuring appropriate PL opportunities for staff – up front, and ongoing, is likely to lead to change in practice.

- Articulate outcomes for the implementation process ensuring a clear focus for monitoring throughout, and specify final outcomes for students along with a plan to evaluate each outcome.

A key aspect of any implementation plan is that a clear line of sight can be tracked between the problem identified (the ‘why’), and the desired outcomes (the ‘so what?’).

The team at WSSC focused their plan on building staff and student capacity to improve students’ ability to tackle their learning challenges with increasing independence, by choosing the best strategy and approach appropriate to the content they were engaging with. For example, would the most effective approach to learning material involve practise testing or highlighting? (Vaughan & Schoeffel, 2019).

Figure 1. Implementation Plan – Metacognition at WSSC

WSSC developed a plan within the PEARLS PL that was structured according to problem, intervention description (active ingredients), implementation activities, implementation outcomes, and final outcomes. After only one year of implementation, the team have enacted many of the elements they set out to – with others being adapted to meet the changing needs of teachers and students.

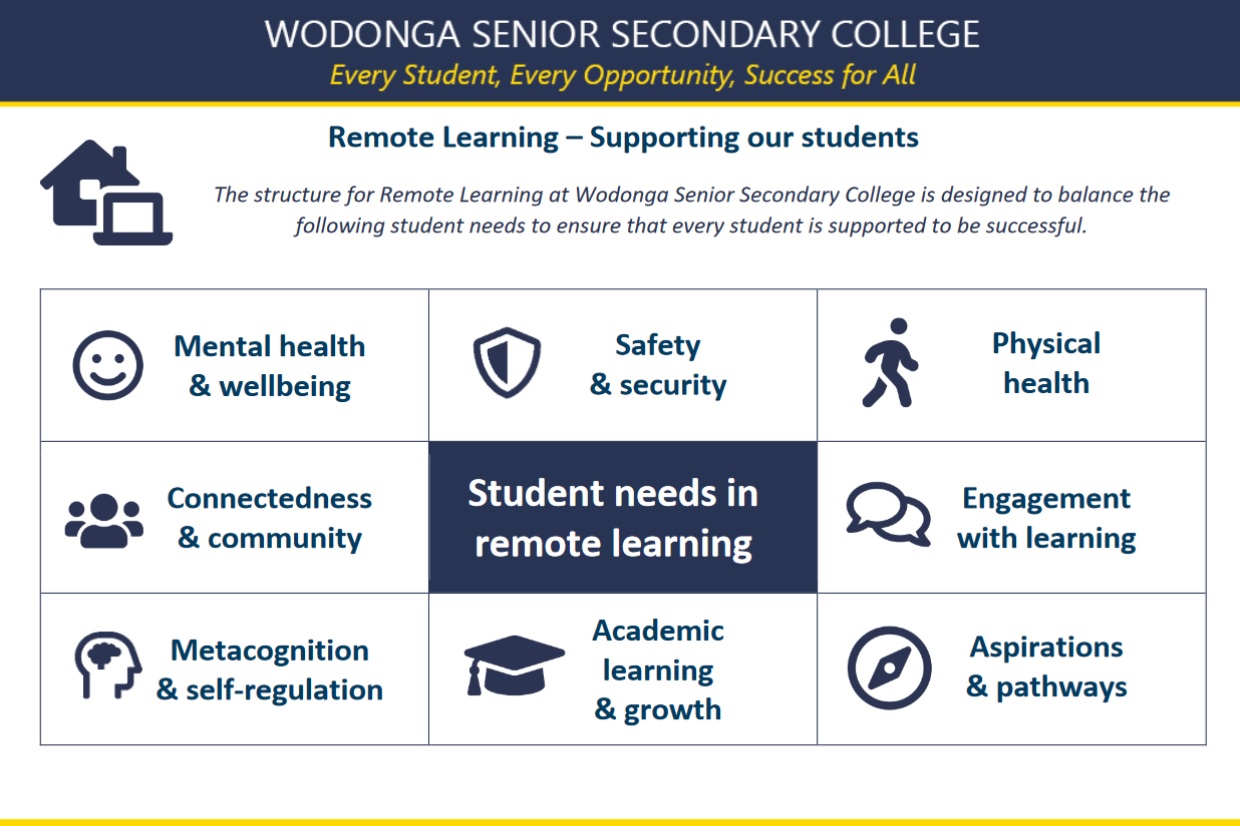

Having articulated this plan, WSSC leaders and staff were well prepared to adapt to the challenges facing Victorian schools during COVID-19. The school rapidly developed a Remote Learning framework, shown in Figure 2, which focused on wellbeing and promoting high-impact strategies – such as metacognition and self-regulation – to continue the development of each student.

Figure 2. Response to supporting students’ needs in remote learning

[Image: Wodonga Senior Secondary College]

Outcomes to date

While it is still too early to determine the impact of this plan on student outcomes at the cohort level, early indicators suggest that implementation is moving towards reaching these goals. There has been a clear increase in teachers explicitly teaching and modelling metacognitive strategies, supported by the frameworks and policies that have been developed, and this will be continually monitored through staff feedback.

The remote learning opportunity provided by COVID-19 has led to students being exposed to the common language earlier than initially planned, and teachers have been provided with short videos on metacognitive approaches specifically designed to address the challenges of remote learning.

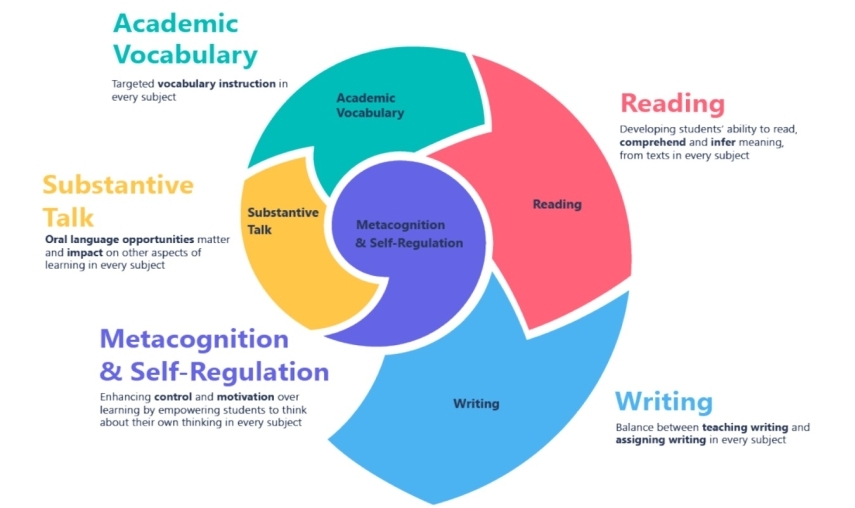

With momentum now building around metacognition, supported by the growing capacity of staff, the work is being embedded through other aspects of the teaching and learning program. WSSC has developed a literacy and metacognition strategy (see Figure 3) to guide the school in literacy for the next five years, articulating the central importance of metacognition in the literacy curriculum implementation and development.

Figure 3. WSSC Literacy and Metacognition framework

[Image: Wodonga Senior Secondary College]

The team that developed the implementation plan has recognised the opportunity to influence future students and is working alongside local primary schools to run PL for their teachers and leaders. These sessions have been well attended and positively received. By focusing on both their own students, and those in surrounding schools, WSSC staff are empowering learners throughout their community.

The metacognitive approaches embedded into teaching practices at WSSC aim to give learners the best possible chance of success within their schooling, increasing both retention of students and achievement levels, along with the skills to become independent, life-long learners.

References

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2020). Guide to understanding the Index of Community Socio-educational Advantage (ICSEA). https://www.myschool.edu.au/media/1820/guide-to-understanding-icsea-values.pdf (421 KB)

Education Endowment Foundation. (2019a). Evidence for Learning Teaching & Learning Toolkit: Education Endowment Foundation. Metacognition and self-regulation. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/teaching-and-learning-toolkit/metacognition-and-self-regulation

Education Endowment Foundation. (2019b). Putting evidence to work: A school's guide to implementation. Implementation theme - Active Ingredients. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Implementation/EEF-Active-Ingredients-Summary.pdf (283 KB)

Quigley, A., Muijs, D., Stringer, E., Deeble, M., Ho, P., & Schoeffel, S. (2019). Metacognition and self-regulated learning. https://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/guidance-reports

Sharples, J., Albers, B., Fraser, S., Deeble, M., & Vaughan, T. (2019). Putting Evidence to Work: A school's Guide to Implementation. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/guidance-reports/putting-evidence-to-work-a-schools-guide-to-implementation

Vaughan, T., & Albers, B. (2017, June 20). Research to practice – implementation in education. Teacher magazine. https://www.teachermagazine.com/articles/research-to-practice-implementation-in-education

Vaughan, T., & Schoeffel, S. (2019, December 13). Building students’ metacognition and self-regulation. Teacher magazine. https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/building-students-metacognition-and-self-regulation

Vaughan, T., Borton, J., & Sharples, J. (2019, April 15). School improvement: Sowing the seeds of success. Teacher magazine. https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/school-improvement-sowing-the-seeds-of-success

As a school leader, how can you and your leadership team develop structures and policies to support teachers to implement metacognition within their classroom practice?

Thinking about your own context, can students articulate where they are at with their learning and what they need to do next? How can you embed effective metacognitive practices within your classroom to encourage independent learning practices within your students?