The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) measures the knowledge and skills of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science and reading, and how well they are prepared to use these to meet real-life opportunities and challenges. In this content series, we delve deeper into the latest PISA data to explore how education systems are working to lift student outcomes.

Today’s article focuses on ‘resilient’ education systems. The OECD report highlights Japan, Korea, Lithuania, and Chinese Taipei as showing resilience. Teacher spoke to OECD PISA National project manager for Lithuania, Rasa Jakubauskė, and Co-national Project Manager OECD Survey for Social and Emotional Skills, Patrick Newell, about what these 2 countries do differently.

A lot has happened between the 2 most recent PISA test cycles in 2018 and 2022. Rising teacher shortages and a sudden and drastic shift to online learning during a global pandemic, to name just 2 issues, have been challenging to navigate.

And, according to the PISA 2022 report released at the end of last year, these challenges have contributed to a trend of unprecedented decline in student performance.

No change in the OECD average over consecutive PISA assessments up to 2018 has ever exceeded four points in mathematics and five points in reading: in PISA 2022, however, the OECD average dropped by almost 15 points in mathematics and about 10 score points in reading compared to PISA 2018.

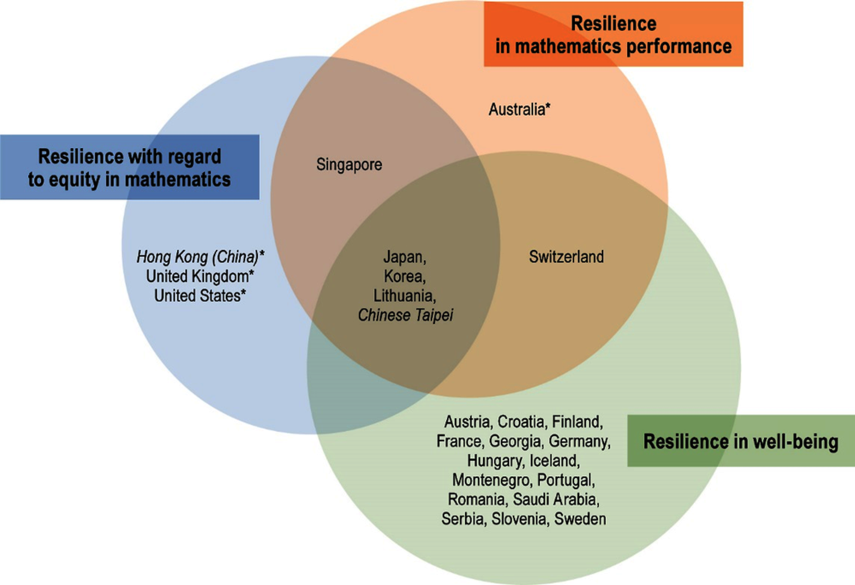

Despite the challenges of the last few years, PISA 2022 highlighted a small number of countries and partner economies for their resilience during the latest assessment cycle. They performed at or above the OECD average, and maintained or improved their own PISA 2018 results, in 3 key areas: mathematics performance, equity in mathematics performance, and student wellbeing.

While several participating economies and countries performed well in one or 2 of these areas, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, and Chinese Taipei were resilient in all 3.

[Image: OECD, 2023]

OECD PISA National project manager for Lithuania, Rasa Jakubauskė, and Co-national Project Manager OECD Survey for Social and Emotional Skills, shared details of some of the initiatives that are happening these 2 countries.

Resilience in mathematics performance

Digitally driven learning

Long before the pandemic, Lithuania had a strong focus on digital literacy – recognising its importance for an increasingly digital world.

‘Even before the pandemic, a significant number of schools were using electronic diaries and certain digital learning resources and communication environments,’ Jakubauskė tells Teacher. ‘[Additionally], e-testing was not completely new to Lithuanian students and teachers.’

That meant that when COVID-19 disruptions hit, students were already well prepared to learn online. According to the PISA 2022 report (OECD, 2023), 84% of Lithuanian students say they feel confident using video communication programs to learn, compared to the OECD average of 77%.

Digital training for teachers

For students to be confident digital learners, teachers need to be confident digital teachers.

‘[In Lithuania] the digital literacy competence of teachers … has been consistently in focus since 2007,’ says Jakubauskė.

That support includes information technology specialists to support teachers in building their confidence of using digital technologies and incentives for teachers to integrate digital technologies into lessons. Over 90% of students in Lithuania attend schools where their teachers are incentivised to integrate digital devices in their teaching (OECD, 2023).

Jakubauskė says in 2020, 71% of teachers said they felt quite confident when using information and communication technologies – that’s despite 81% having had no experience with distance education prior to the pandemic.

An existing culture of out-of-school learning

Newell says that the existing out-of-school learning culture in Japan meant that students were already experienced at learning independently and away from the classroom, so they were well placed to do well even during remote learning.

‘Most the kids are already going to after school [programs]. So, they are already used to learning well beyond [what they learn] within their school environment and beyond just doing the homework that's been given to them by school,’ he tells Teacher.

Parental support

As noted in the PISA 2022 report, education systems with positive trends in parental engagement in student learning between 2018 and 2022 showed greater stability or improvement in mathematics performance.

This is something that Newell says is extremely prevalent in Japan.

‘Learning at home required parents to actually take a much more active role in the learning … because parents [in Japan] are highly educated, they can quickly shift and help their children.’

Interestingly, Newell notes that this parental involvement isn’t restricted to just home life, or during the pandemic when students were learning at home – parents are heavily encouraged by schools to get involved with the school community.

‘In my daughter’s school, parents are required to earn 16 points each year for helping out in the school … [for] doing different activities throughout the year.’

This meant that the additional parental support required during remote learning may have been less of a challenge for parents in Japan, who were already actively involved with the school and their children’s education.

‘[It] helped mitigate the effects of disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic and contributed to the overall stability and improvement of student performance,’ Newell adds.

Resilience and equity in mathematics

Ensuring all students have what they need to learn

In his new column, to be published in Teacher next week, OECD Director for Education and Skills Andreas Schleicher explains that ‘PISA 2022 found a negative association between a lack of or inadequate digital resources and student performance. High performing education systems ensure that every student has access to a digital device.’

Both Lithuania and Japan have made efforts to address this, and both now have a higher ratio of tablets/computers per student in disadvantaged schools (compared to advantaged schools) and in rural schools (compared to urban schools). Additionally, during remote learning, both these countries rapidly distributed the necessary tools to those that did not have them, ensuring that students weren’t disadvantaged due to the financial costs of remote learning.

‘… about 35,000 students from socially vulnerable families did not have sufficient opportunities to learn from home … in spring 2020 more than 35,000 tablets and laptops, and unlimited internet access cards for students were bought and distributed,’ says Jakubauskė.

Ensuring additional support is available to all

‘Many Japanese students receive additional support outside of school through private tutoring and supplementary educational programs, known as juku,’ Newell explains.

While some of these programs can be expensive – and Newell acknowledges there is some inequity in this area – he adds that there are a lot of programs that are cheap or free, meaning everyone can access that additional support on some level.

This additional learning support is just one of the programs Japan offers to help improve equity. Other initiatives include subsidies for school supplies and activities and free or reduced cost school lunches.

Resilience in wellbeing

Creating a sense of belonging and community

According to Newell, Japan fosters a community feeling in schools that create a sense of belonging and responsibility for each other and their environment.

‘[When students] arrive there's usually some students greeting students in front of the door … they serve each other lunch … the children clean the school, so it's not like, ‘oh, let me just throw my garbage here’ [because] you're going to be cleaning it up.’

Additionally, while not mandatory, students are strongly encouraged to join at least one club.

‘Clubs provide opportunities for students to pursue interests, develop new skills, and build friendships outside the classroom … clubs often involve teamwork and leadership roles, helping students learn to work together and take on responsibilities.’

Strict anti-bullying policies

According to PISA 2022 student questionnaire data, all Australian states and territories had rates of bullying above the OECD average (De Bortoli et al., 2024). Japan, on the other hand, has rates well below the average, something that Newell says is helped by having clear policies and guidelines in this area.

‘Schools are required to have measures in place to prevent and address bullying. [These] include clear definitions of bullying, procedures for reporting, and mechanisms for dealing with incidents … teachers are trained to recognise signs of bullying.’

Wellbeing support

Supporting student wellbeing also means providing additional support when needed, such as during times of heightened uncertainty and change.

‘In 2021,’ says Jakubauskė, ‘a Wellbeing Program was provided by educators to improve students’ wellbeing and strengthen communication and cooperation skills [during remote learning].’

Stay tuned for Andreas Schleicher’s new Teacher column – Equity lessons for the AI era from PISA 2022 – published on Friday 2 August.

References

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning During – and From – Disruption. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a97db61c-en.

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., Friedman, T., & Gebhardt, E. (2024). PISA 2022. Reporting Australia’s results. Volume II: Student and school characteristics. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-726-7

In this article, Patrick Newell notes that, in Japan, it’s almost an expectation that students will be involved with at least one club – something that can help to build belonging in students. What percentage of students at your school are in a club? How could you encourage more students to participate?

Rasa Jakubauskė says that in Lithuania, they recognised certain students didn’t have the tools needed to effectively work from home and worked to quickly address this. When you set out-of-class work, do you ensure it’s achievable by all students – including those that may have limited access to digital resources?

One of the things that helped Lithuania is their strong focus on digital literacy, for both students and teachers. As a school leader, do your teachers feel confident in using technology? What are their professional development needs? How do you support them to improve their skills and classroom practice in this area?