In their many years of teaching chemistry to first-year university students, Dr Gregory Watson and Dr Jolanta Watson from the University of the Sunshine Coast have found that it is a subject many students find challenging, with numerous fundamental concepts that can be overwhelming, difficult to understand and, at times, quite abstract. For teachers introducing students to the periodic table for the first time, they recommend beginning with a series of pre-periodic tables before presenting the ‘real’ chemistry periodic table. In today’s article, they explain what the introductory non-chemistry tables are, and how they progressively demonstrate new key aspects to help students’ understanding.

The amazing thing about the ‘normal’ periodic table is that it contains so much information, holding the key to many chemical (and indeed many scientific) concepts such as atomic sizes, and trends like reactivity.

For teachers introducing students to the periodic table for the first time, we suggest you begin by presenting a series of 3 non-chemistry tables and focus on simple key characteristics of the table construction. These include organising familiar objects into columns, rows, blocks and by colour, through numbering, the use of abbreviations for various objects, combining individual objects together, and demonstrating trends transitioning across and down the tables.

The activities explored in this article can be adapted for students of all ages – from primary to secondary school, or even at a tertiary level. How much time you spend on each pre-periodic table is context dependent. We’ve found that you can spend one whole lesson on superheroes getting primary school students to organise the heroes into columns or blocks, but for secondary students it could take only 5 to 10 minutes with a class discussion.

However, even before we show the tables to students, we ask them: ‘What would be the best way to communicate to someone a number/set of objects, and aspects/features of those objects? Could it include a list on a piece of paper, a set of pictures, a video, a TikTok, or another method? Can this be done in a more efficient way? What about a single diagram in the form of a table which organises the objects into various groups and revealing certain trends?’

The periodic table of superheroes – thinking about organisation

This is where we typically introduce our first table – The Table of Superheroes – which demonstrates the general layout of the periodic table (online you will find several or you can make/adapt your own). Each element location is replaced with a single superhero such as Superman, Wonder Woman, The Green Lantern, etcetera.

We’ve found that this engages the students and introduces them to table organisation through various attributes by placing the superheroes into rows and columns, forming various characteristic blocks, and introducing a numbering system across and down the table. The question of which blocks we would place certain superheroes into and how to base such a decision gets them thinking. For example, would you categorise them by gender, strength, superpower, super-suit colour, presence of a cape, new versus old superhero or DC versus Marvel.

The periodic table of meats – abbreviations

Before too many arguments over which superhero is the best or strongest, we move on to other examples of pre-periodic tables, such as the periodic table of meats (also available online and easily found with key word searches). For this table you could place the various meats in blocks: fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, poultry, game, native, red and white meat proteins.

We also introduce the concept of abbreviations, where we encourage students to think of simple characters which would represent various meats, such as B for Bacon, Sq for squid or Lb for lobster. This segues well into combining objects together in a certain ratio. Working in a restaurant is a useful scenario. Asking students if they were a waiter/waitress and their ordering tablet stopped working, they would need to write orders quickly, preferably in shorthand. So, for a customer who’d ordered 2 portions of lobster (Lb) and one portion squid (Sq), they could simply be expressed by writing Lb2Sq.

The periodic table of fruits and nuts – size and transition

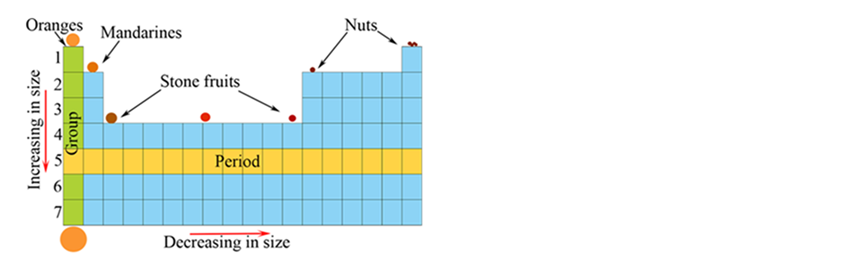

The final table presented prior to our introduction of the chemical periodic table is the Periodic Table of Fruit and Nuts (Watson et al., 2021), a basic example of which is shown in Figure 1. This introduces another layer of organisation – size and transition. The diagram we present simply shows circles of various sizes and colours which represent the fruits and nuts, however one could easily find pictures of fruit and nuts and place them appropriately in the table, particularly for very early learners in primary school.

This table demonstrates that objects can be placed based on physical characteristics and trends. In this case, transitions across the table from left to right, become less fruity and more nutty, which is an analogy to transitioning from metallic to non-metallic elements across the periodic table. Note that we have kept similar related fruits together, for example oranges and mandarins for the first 2 columns (representing the alkali and alkaline earth metals).

Transitioning down the table, we see an increase in size which is analogous to atomic size changes due to larger numbers of electron shells. Transitioning is also demonstrated across the table from left to right, which results in objects becoming smaller in size. Thus, the table shows that objects can be placed in the table according to trends with transferable ideas that are used when understanding the ‘real’ chemical periodic table of elements.

A representative fruit and nut ‘periodic’ table. The table transitions from fruit to nuts, moving across the table from left to right, and relative size, which transitions both across and down the table demonstrating analogies to the chemical periodic table.

The examples of tables we have shown progressively demonstrate one or more new key aspects which may help prior to introduction of the periodic table and can easily be modified to engage different targeted audiences. There are many variations and other tables one could use (such as the periodic table of fish, plants, iPad apps, planets/suns/moons, cars, dogs, eggs…) with the list being extensive and allowing educators to play with these ideas.

References

Watson, G. S., Green, D. W., & Watson, J. A. (2021). Introducing students to the periodic table using a descriptive approach of superheroes, meats, and fruits and nuts. Journal of Chemical Education, 98(2), 669-672.

Have you used analogies or non-scientific examples before to teach scientific concepts to your students? What worked well, and what didn’t?

How do you currently introduce the periodic table to students? What prior work (including vocabulary) do you do to help scaffold student understanding? Which of the tables suggested by the authors in this article could be most effective for your context?