Creativity is not just an artistic endeavour, it is a crucial skill for problem-solving, innovation and adaptability across all fields. In a post-AI world, creativity is more crucial than ever, embodying the uniquely human capacity to drive societal progress (Rafner et al., 2023).

For Australian teachers, the challenge and opportunities lie in nurturing this creative potential in every student. The starting point is to embrace creativity as a teachable skill, that all students have capacity for to varying degrees (Plucker et al., 2004), rather than a fixed trait, and to recognise the importance of subject-specific knowledge in developing creative expertise (Kaufman, 2016).

Although historically associated with a more inquiry-based approach, this article focuses on the development of creativity as part of a knowledge-rich curriculum. It describes the role of subject-specific knowledge in the development of creative expertise and highlights effective strategies for nurturing creativity with specific examples from English, Science and Technology, and Creative Arts.

The role of subject-specific knowledge in creative production

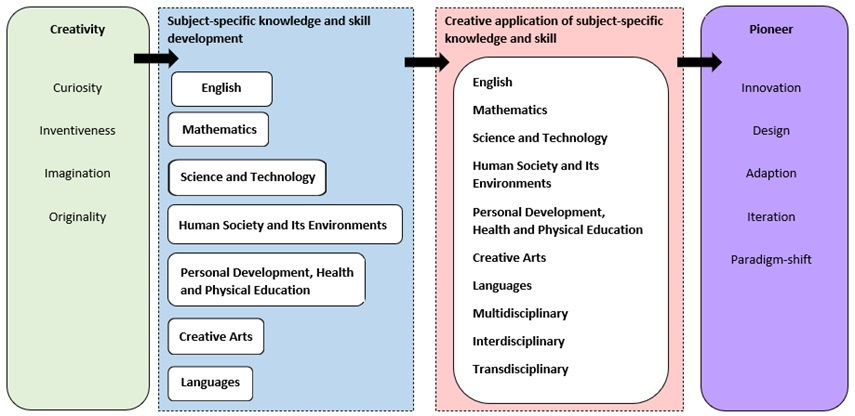

Subject-specific knowledge is fundamental in providing the foundation for creative production (Dumas et al., 2024). As illustrated in Figure 1, creativity is characterised by curiosity, inventiveness, imagination and originality. This creativity is guided by personal experiences and general ideas. As students acquire specialised knowledge and skills in specific subjects at school, the opportunities to develop creative potential evolves.

Creative applications and production are often shaped by the subject expertise, conventions, or practices within a field, and hence require specific knowledge that can contribute unique contributions to a field, including the evolution of current understandings. This pioneering work is acknowledged due to an understanding that the creator is both knowledgeable and reliable in the field, and such contributions may lead to significant advancements or the opening of new frontiers in science, technology, art, business, or other areas.

Figure 1: The development of creative expertise through knowledge and skill development and its creative application. (Informed by Barbot et al., 2015; Dumas et al., 2024; Gagne, 2021; Jarvin & Subotnik, 2021; Lubart, 2018; Subotnik et al. 2023; Vygotsky, 2004).

Examples from English, Science and Technology and Creative Arts

Creating a supportive classroom environment is crucial for fostering the risks and experimentation necessary for developing creative expertise (Alexander, 2023; Lubart, 2018). An inclusive and supportive classroom environment encourages the notion of risk-taking for all students. As Sir Ken Robinson declared: ‘If you’re not prepared to be wrong, you will never come up with anything original,’ (Robinson, 2006). In this section, we illustrate how creativity can be nurtured across 3 subject areas.

- English – techniques such as elaboration and adaptation enable students to expand on existing texts and reimagine literary work (Beghetto et al., 2014; Fogarty, 2021)

- Science and Technology – the processes of inquiry and production whereby students explore scientific questions, experiment and design and create innovative solutions encourage creativity (Jarvin & Subotnik, 2021; Sternberg, 2021; Taber, 2016; Watters, 2021)

- Creative Arts – perspective-taking and creator study allow students to explore and understand different viewpoints and talent trajectories, which can be a springboard for their own artistic expression (Celume & Zenasni, 2022; Lubart, 2018).

Nurturing creativity in English

Elaboration and adaptation are powerful strategies for nurturing creativity in English. While elaboration encourages students to expand on ideas creatively, adaptation takes this a step further by inviting them to reinterpret or reimagine existing literary works.

To use elaboration in the classroom, you might ask students to select a single word or sentence from a text and use it as a springboard to create a story, poem, picture, or song. Another approach is to have students write about what happened before the events of a story begin. This prequel exercise fosters critical thinking about character motivation and plot development while providing students with the freedom to invent backstories and settings.

To use adaptation students may rewrite, expand or modernise selected texts. This might involve updating the setting of a Shakespearean play to a contemporary context or exploring what a familiar story might look like if told from a different character’s perspective.

Both elaboration and adaptation depend on a deep understanding of text, supported by an initial close reading and subject-specific knowledge about textual forms and features.

Nurturing creativity in Science and Technology

Two strategies that may be used in Science and Technology to nurture creativity are inquiry and production.

Inquiry in Science and Technology involves asking questions and collecting evidence to examine, test, and further develop ideas – often in a hands-on, experimental manner. To use inquiry effectively in a knowledge-based curriculum, it is helpful to foster a culture of questioning and exploration. For example, encouraging students to ask questions such as ‘What would happen if …?’ or ‘Why were some elements of the Periodic Table discovered only recently?’. Questions can also be prompted by examining multiple concepts, including incomplete or incorrect ideas to challenge student thinking. Teachers need to be both open to the unexpected and flexible in order to challenge student perspectives in a way that ‘forces’ the student to reassess their thinking. The activity of inquiry involves students making predictions (or scientific hypotheses) and testing them with sometimes original, and sometimes creative, questions or methods.

Production in Science and Technology involves developing original design ideas and creating unique or novel products. The first step of production is identification of something that requires a creative solution, supported by a range of resources and student choice. For example, teachers may encourage students to connect with diverse viewpoints or examine historical and contemporary design solutions from a range of cultures to provide a richer context for their creative work. Providing opportunities for students to negotiate, experiment, and make decisions in production underpins creative process.

Nurturing creativity in Creative Arts

Teachers can effectively nurture creativity and socio-emotional development in the Creative Arts classroom by employing unique and individual perspective-taking and studying the lives of creative individuals.

Perspective-taking helps students to step into the shoes of different characters, audiences, or creators, allowing them to explore diverse viewpoints and motivations. The creativity is nurtured through the novel and unique development of the perspective. For instance, students might engage in improvisation or role-play activities, assuming different characters from unique perspectives in time or space, or create artwork from the perspective of historical figures or fictional personas. This creative practice deepens their understanding of others' emotions and intentions, leading to richer understandings.

Additionally, teachers can guide students in researching and analysing the lives and creative processes of renowned artists, performers, or composers. By examining how these experts developed their craft and overcame challenges, students can gain insights into their own creative development. Such reflection helps them identify both beneficial and challenging aspects of their creative growth and development.

Creative expertise can and should be developed alongside the acquisition of knowledge and skills. Teachers can provide opportunities through the delivery of their curriculum to develop creative potential in all students.

References

Alexander, P. A. (2023). Creating a motivating learning environment: Guiding principles from philosophy, psychology, and pedagogy. In M. Bong, S.-I. Kim, & J. Reeve (Eds.), Motivation science: Controversies and insights. Oxford University Press.

Barbot, B., Besançon, M., & Lubart, T. (2015). Creative potential in educational settings: Its nature, measure, and nurture. Education 3-13, 43(4), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2015.1020643

Beghetto, R. A., Kaufman, J. C., & Baer, J. (2014). Teaching for creativity in the common core classroom. Teachers College Press.

Celume, M.P., & Zenasni, F. (2022). How perspective-taking underlies creative thinking and the socio-emotional competency in trainings of drama pedagogy. Estudos de Psicologia, 39. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202239e200015

Dumas, D., Forthmann, B. & Alexander, P. (2024) Using a model of domain learning to understand the development of creativity. Educational Psychologist, 59:3, 143-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2023.2291577

Fogarty, E. A. (2021). Language arts curriculum for gifted learners. In Stephens, K.R. & Karnes, F.A. (Eds.), Introduction to curriculum design in gifted education (pp. 129-149). Routledge.

Gagné, F. (2021). Implementing the DMGT’s Constructs of Giftedness and Talent: What, Why, and How? Handbook of Giftedness and Talent Development in the Asia-Pacific, 71-99. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3041-4_3

Jarvin, L., & Subotnik, R. F. (2021). Understanding elite talent in academic domains: A developmental trajectory from basic abilities to scholarly productivity/artistry. In Dixon, F.A. & Moon, S.M. (Eds.), The handbook of secondary gifted education (pp. 217-235). Routledge.

Kaufman, J. C. (2016). Creativity 101. Springer publishing company.

Lubart, T. (2018) Creativity across the seven Cs, chapter in Sternberg, R. J., & Kaufman, J. C. (Eds.). The nature of human creativity (pp 134-146). Cambridge University Press.

Plucker, J.A., Beghetto, R.A. & Dow, G.T. (2004). Why Isn’t Creativity More Important to Educational Psychologists? Potentials, Pitfalls, and Future Directions in Creativity Research, Educational Psychologist, 39(2):83–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_1

Rafner, J., Beaty, R. E., Kaufman, J. C., Lubart, T., & Sherson, J. (2023). Creativity in the age of generative AI. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(11), 1836-1838.

Robinson, K. (2006, February). Ken Robinson: Do schools kill creativity? [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity

Sternberg, R. J. (2021). Transformational creativity: The link between creativity, wisdom, and the solution of global problems. Philosophies, 6(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies6030075

Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Corwith, S., Calvert, E., & Worrell, F. C. (2023). Transforming gifted education in schools: Practical applications of a comprehensive framework for developing academic talent. Education Sciences, 13(7), 707.

Taber, K. S. (2016). ‘Chemical reactions are like hell because…’: Asking gifted science learners to be creative in a curriculum context that encourages convergent thinking. In Interplay of creativity and giftedness in science (pp. 321-349). Brill.

Watters, J. (2021). Why is it so? Interest and curiosity in supporting students gifted in science. Handbook of giftedness and talent development in the Asia-pacific, 761-786.

Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10610405.2004.11059210

This article has shared some practical examples of how to nurture creativity in different subject areas. How do you foster creativity in your own classroom?