Last month, the OECD published the PISA 2022 results for the creative thinking skills assessment, revealing that 15-year-old students in Australia achieved a mean score higher than the OECD average in this area. In their report, the OECD reiterated that creative thinking skills can be taught in schools. So, what can this look like in the classroom? In this article, ACER Senior Research Fellow, Dr Claire Scoular, shares 6 considerations for when you’re teaching creative thinking skills.

There is growing consensus internationally that creative thinking needs to be cultivated to help learners succeed. Beyond identifying the importance of the skill, however, there is little guidance on how to develop and teach it, due in part to a lack of understanding or even agreement about the nature of creative thinking as a skill, including what constitutes its fundamental building blocks, and how it develops and changes in a learner. At ACER, we’ve been researching effective practice and, in this article, I offer 6 suggestions for teaching and assessing creative thinking in the classroom.

1. Use a framework to break skills down into manageable chunks

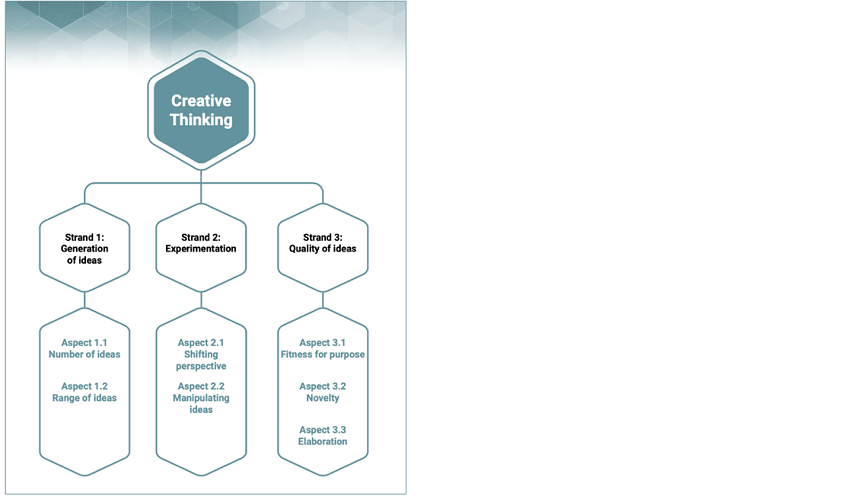

To be able to teach and assess creative thinking effectively, we need to have a clear and robust definition of what creative thinking is: what processes and end-qualities it entails, and therefore what observable behaviours and features would reasonably serve as evidence of it. This is the goal of ACER’s creative thinking framework. Given the complex nature of creative thinking, the framework breaks what is often thought of as an unpredictable and elusive construct down into manageable bite size chunks, so a teacher can focus on one aspect rather than tackling them all at once.

ACER’s creative thinking skill development framework (Ramalingam, 2020). Image: ACER

The aim of developing such resources is to support teachers to better understand these skills and to make criterion-based judgements while observing student behaviours, interpreting student assessment data, and monitoring progress.

2. Structured brainstorming activities to generate ideas

Brainstorming is a great exercise to do with students to generate ideas. Counting the number and range of ideas students produce has a long history in creativity assessment. Although it’s not so much the quantity that counts, but that generating more ideas typically leads to more options for manipulating or combining ideas to come up with good solutions.

While generating many ideas increases the likelihood that a creative one will be among them, if all ideas are similar to each other, a creative idea is less likely to emerge. Therefore, we can look together at the number and range of ideas during brainstorming tasks to give us an indication of the fluency and flexibility of student creative thinking. Teachers can pause and ask students to reflect: ‘Are we just coming up with the same idea in different words? How many ideas do we actually have? What sorts of categories could we create from these ideas? Let’s try to think of ideas beyond the categories we already have, to see if a really original idea will emerge.’

3. Teach the aspects of creative thinking explicitly

If a learner is provided with an understanding of what the creative thinking skills are and how they can be applied, then these skills will be more accessible and applicable. With sufficient understanding of the skill, and its associated aspects, learners can build a metacognitive understanding of their own development. They can understand what it means to be a good creative thinker and reflect on their ability to apply these skills in any given learning area.

It’s useful to be explicit with students about what the aspects of creative thinking are, and which aspects you are teaching them or asking them to apply when engaged in learning tasks. Students are more creative when prompted to ‘be creative!’ but being more explicit than this can support students’ application of the skill. For example, suggesting they try to come up with some novel combinations, or try to consider the issue or problem from someone else's perspective.

Fundamentally, proficient creative thinkers ensure ideas are going to be effective or fit for purpose. This aspect acknowledges that creative thinking has a purpose, and if the end product is of no value or does not suitably fulfil a desired function (even if that suitability or value is only appreciated by the individual who created it), then it does not fully demonstrate creativity. If students are aware of this aspect of the skill, they can reflect on how well they are addressing and achieving this. The levels of skill development for each aspect can be used as a metacognitive tool for students.

4. Set students ill-defined problems to solve

If students are only given well-defined problems to solve, with well-established solutions that simply need to be recognised and applied, they are not engaged in ‘possibility thinking’, which is the essence of creative thinking. Instead, ill-defined problems allow fertile possibilities and a range of solutions. It’s helpful to ensure it is an authentic problem that students can be engaged in finding out the solution, and a complex enough problem that it can be looked at from multiple perspectives and explored through multiple pathways or solutions.

5. Collaboration and peer feedback

Students can also be the facilitators of skill development in addition to teachers. Working with other students can support development in several of the aspects, helping generate ideas, looking at problems from different perspectives, and getting feedback on the suitability of ideas. Working with others though can be particularly useful in elaborating your ideas. Sharing your ideas with others can prompt thinking around how and why an idea might work, and what the consequences of it might be.

While the creativity of some ideas may be immediately obvious, the need to elaborate an idea is particularly important when the idea is sufficiently imaginative and unusual that it’s difficult for others to recognise how it would work, or why it represents a clever or original approach to the challenge or problem. It can also help with identifying the optimal solution or decision from a longer list of options. The focus of discussions can be directed to identify interesting possibilities. For example, asking students to frame their feedback as ‘What if…’ or ‘Could you…’ questions. If they are working collaboratively, then these could be ‘What if we…’ or ‘Could we…’, to stimulate combining ideas from the team.

6. Focus on progress

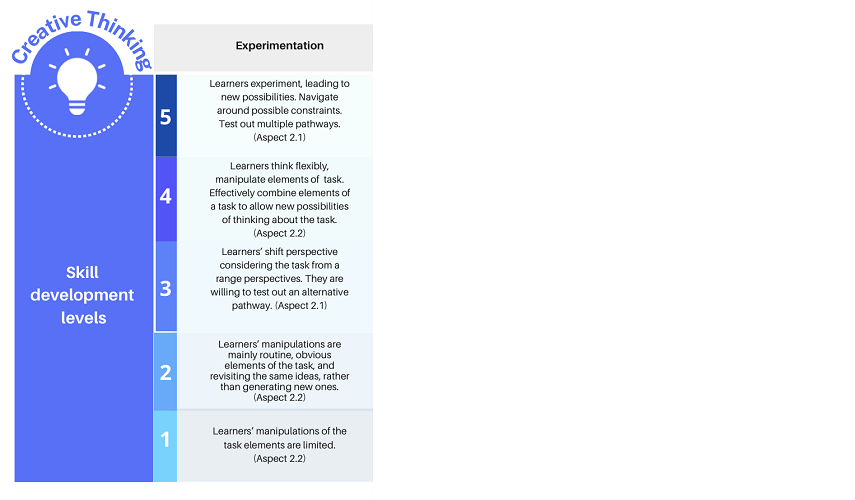

Ultimately the goal of embedding the skill in teaching practice is to progress the skill in students. The image below shows ACER’s levels of skill development for creative thinking that focuses on the ‘Experimentation’ strand and what behaviours we expect students to demonstrate at these different levels.

Levels of skill development for Experimentation, adapted from Ramalingam, 2020. Image: Claire Scoular

These levels can support understanding of these aspects and how they develop. They can also support teachers to appropriately target teaching interventions at a student’s level of ability. For example, students who demonstrate being less proficient at shifting their perspective on a problem to generate novel ideas can be taught techniques and strategies for reconsidering problems and solutions from a different ‘angle’ (for instance, from the perspectives of different stakeholders to see other causes to a problem, or to explore less obvious uses, properties and qualities of objects or solutions).

Commonly used examples of such classroom strategies include De Bono’s Six Thinking Hats which uses 6 colour-coded hats to represent different ways of thinking. For example, one hat encourages you to look at the facts, while another is for emotional or instinctual perspectives. The general approach encourages students to playfully experiment with possibility thinking – looking at possibilities rather than limitations to solve problems or generate ideas creatively.

There are lots of ways we can embed more creative thinking into our classrooms, some of which require more preparation, but many can be short additions. For example, prompting to students to consider questions, or responses, in a different way, or taking a moment to pause and have students reflect on what they are doing and why. But importantly, breaking the skill down and working with the aspects can help to ensure a consistent, effective, and efficient way of embedding the skill in student learning.

References

Ramalingam, D., Anderson, P., Duckworth, D., Scoular, C., & Heard, J. (2020). Creative Thinking: Skill Development Framework. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/ar_misc/40

In this article, Dr Claire Scoular says that structured brainstorming activities can be a great exercise to generate ideas and that looking together at the number and range of ideas as a class can help give an indication of student creative thinking.

Reflect on the last time you led a brainstorming activity in the classroom. Did you take the time to pause and ask students to reflect on their ideas? How did this enhance student learning?