A new report has provided 6 practical recommendations for improving primary science. Drawing from international evidence and consultation with a panel of expert practitioners and academics, it provides guidance on how to make meaningful improvements to teaching. In this article, we take a look at one of the 6 recommendations – developing students’ scientific vocabulary.

Young children are naturally curious about the world they inhabit. And, according to a report published late last year by Evidence for Learning (E4L) on Improving Primary Science, high-quality science is key in building this curiosity, helping young students find joy in understanding the world around them.

However, as the report quickly outlines, ‘Like the other core subject areas of the curriculum, in science, there is a stubborn gap in achievement between students experiencing disadvantage and their classmates’.

Put simply, while children of all backgrounds show an interest in science at a young age, not all attain the necessary skills or desire to progress to further STEM study. The E4L report outlines 6 key recommendations to help address this:

- Develop students’ scientific vocabulary.

- Encourage students to explain their thinking.

- Guide students to work scientifically.

- Relate new learning to relevant, real-world contexts.

- Use assessment to support learning and responsive teaching.

- Strengthen science teaching through effective professional development, as part of an implementation process.

Developing students’ scientific vocabulary

As outlined by the report, ‘It is crucial that early science teaching empowers all students to engage fully with science learning, equipping them with the knowledge and skills they need to access opportunities later in life.’

This includes teaching specific vocabulary to build students’ understanding. As noted by one primary teacher, ‘If they don’t have that key scientific vocabulary, and they can’t use it and have a discussion around it, then they’ll face more challenges,’ (Evidence for Learning, 2023).

The report includes this example to illustrate the challenges limited vocabulary can pose.

Mrs Armstrong, a Year 5 teacher, has been teaching her class about states of matter. The day was hot which was the ideal weather for students to observe the phenomenon of evaporation. She poured some water on the hot pavement and asked the question ‘where did the water go, and why?’ While the students are engaged in conversation and actively listening to each other, they frequently use informal and incorrect terms like ‘disappear’, ‘jump’, ‘soaked up’, ‘zapped away’. Some students have a misconception that the water is absorbed by the pavement, some state it could be a cloud but it should be visible, and many use the word ‘disappear’ to refer to evaporation and believe that the water has disappeared forever

From this example we can see that even though the students are actively engaged and curious, and some even hold a basic understanding of what is happening, without the right vocabulary they can’t further their understanding, nor accurately describe it.

Identifying science specific vocabulary

Before you can explicitly teach the relevant scientific vocabulary, you need to first identify what the vocabulary is.

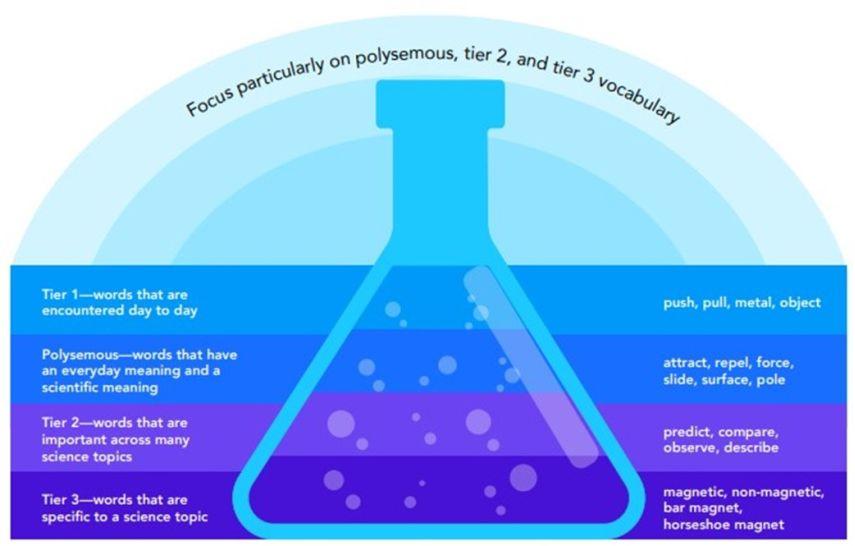

The report’s authors state that, ‘When deciding on which words to explicitly teach, consider the breadth of vocabulary and background knowledge needed to fully access the science being taught.’ They also note that categorising terms you may need can be helpful. Figure 1 shows how words can be categorised into 4 groups.

Figure 1. Types of vocabulary in science – example for ‘forces and magnets’, from Improving Primary Science. (Evidence for Learning, 2023).

Whereas Tier 1 words are most easily understood, and commonly used by primary students to explain difficult concepts and topics, moving away from these words through the introduction of polysemous, tier 2, and tier 3 vocabulary is crucial for building student understanding.

Explicitly teaching new vocabulary

Once the relevant vocabulary has been identified, it must be explicitly taught in a way that is relevant to the students. Otherwise, you risk reinforcing a term that, while able to be memorised and recalled, does not hold any meaning.

Due to the difficulty in grasping scientific vocabulary, the report stresses the need to ‘plan when and how you will introduce new words and definitions, ensuring they link directly to the content being taught, and build on prior knowledge’.

This ensures difficult vocabulary is introduced intentionally, when appropriate and when relevant. Once introduced, the new vocabulary should then be repeatedly engaged with and used in different scenarios to best help students learn and understand its meaning.

The report suggests these steps:

Model the use of the word in context – Provide a clear student-friendly definition or explanation. This can be a good time to call upon tier 1 and polysemous words you identified earlier and that students are already familiar with.

Create context for words that need to be learned – Draw on scenarios that students will already understand. For example, when teaching herbivore/carnivore, consider animals students love and know, with diets they already understand (such as rabbits and lions).

Expose children to the new vocabulary across all literacy activities – Provide multiple opportunities to revisit and engage with the vocabulary. This can be across other subjects and activities, such as including it in writing work, reading, and class discussions.

Use vocabulary approaches that promote rich language connections – Visual aids combined with image creation (such as drawing pictures and diagrams) can also help. In some cases, etymology may be beneficial, for example, highlighting the ‘herb’ in ‘herbivore’.

References

Evidence for Learning. (2023). Improving Primary Science. Evidence for Learning. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/education-evidence/guidance-reports/improving-primary-science

As a primary teacher, think about your own lessons. Do you set aside time in your planning to explicitly teach subject specific vocabulary?

What techniques and activities (such as visual aids) do you employ to help your students better understand difficult topics? How can these be utilised in your upcoming lessons?

Think about an upcoming science unit. On your own, or with a colleague, plan out opportunities to revisit and engage with the vocabulary in other subject lessons.