Educators refer to multiple forms of student data to help them plan out the next steps in teaching and learning, including informal feedback, classroom conversations and written assessments. As Dr Anne Knowles explains in this reader submission, student drawings could also be a useful addition to your toolkit.

Dr Knowles shared this research as a poster presenter at the last ACER Research Conference (Knowles, 2023b). Research posters and multimedia presentations will once again be on display throughout Research Conference 2025 – which takes place in Melbourne on 6 and 7 February.

Action research in the Pacific Group of Christian Schools (PGOCS), New South Wales, has explored how supplementing curriculums with Personal Viewpoints Pedagogy (PVP) in year 5 and 6 classrooms led to change in self-prioritisation, with positive influences on prosocial behaviour (Knowles, 2021 & 2023a; Smith & Knowles, 2021).

In the study – carried out through the PGOCS’ Excellence Centre with research colleague Dr Thomas Smith – written responses were collected from students, alongside freehand drawings. This article discusses how data from these drawings provided valuable insights into students’ thinking and learning.

Student voice at the centre

The PVP focuses on peer discussion at various levels and centres on respectful classroom interactions and self-reflection. Practices integrated into curriculums are designed to help students express their opinions and validate choices, to feel secure to confidently contribute their personal viewpoints, and to listen to and affirm others’ viewpoints. Respectful, considerate interaction is emphasised, with ‘othering’ curbed and inclusivity normalised.

In the PGOCS context, curriculum content is shaped by connections to texts, and concordant Bible-based input. The aim is to engage beyond one’s inner circle, to shift from outgroup to ingroup, encourage prosocial behaviours with concern for others – even at personal cost – overcoming stereotyped and default attitudes.

In the classroom, students were challenged to respond to problematic peer scenarios through discussion and perspective-taking. Drawings placed student voice at the centre of our research – providing comparable, yet distinct, representations of thinking. They offered an effective pre/post lens to assess differences in students’ responses before and after instruction augmented by PVP classroom practices focused on prioritising others.

As Tay-Lim & Lim (2013) note, students’ drawings allow them to contribute ‘authentic, insightful and … influential data’ (p. 79) on how they see themselves in relation to an event.

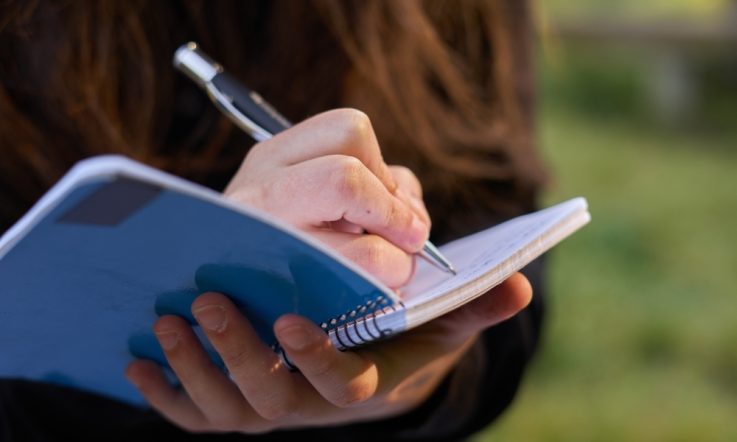

Being adept communicators through drawings, children can overcome linguistic limitations, with even stick figures giving meaning to a student’s inner world (Deguara & Nutbrown, 2018). Indeed, the initial catalyst for using drawings in PVP research came from one student in particular who had poor written proficiency and was inclined to be disruptive but was given a clear voice through this medium (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Response to a year 5 scenario involving a student who keeps borrowing. In this example the speech bubbles and the faces provide valuable insights.

Students make many decisions to show learning as they translate content into visuals – how to represent the relationship, size, shape and relative position between content elements (Miller, 2021).

For teachers, seeing a student’s thinking and understandings in visual form can provide valuable insights into the choices made to represent an idea, and possible preconceptions and misconceptions about curriculum content – the subtleties of what they do and do not yet understand.

Offering students structured opportunities to represent their thinking with drawing offers a window into students’ thinking, an insider’s view of personal viewpoints, and a valuable tool to help assess change in students following curriculum interventions (Bonoti et al., 2019; Tay-Lim & Lim, 2013).

To effectively use students’ drawings as data, Miller (2021) suggests coding student visuals, looking for how facts, relationships, sequences, patterns, and details are represented or misrepresented, and what key elements may have been overlooked.

Themes from student responses

Themes emerged from students’ drawings in our PVP Pilot study (year 5) and Retest study (year 6), regarding students’ proposed involvement and attitudes in resolving problematic peer situations. Cues from relationships, patterns, details and distinctive inclusions and exclusions related to expressions, actions, context, and figures, provided data for the dependent variable ‘Focus on others’ and its 4 categories – Self-Conceit, Conditional love, Unconditional love, Sacrificial love – reflecting Philippians 2:3-4.

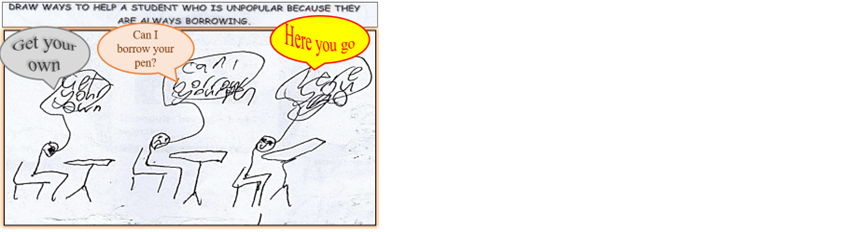

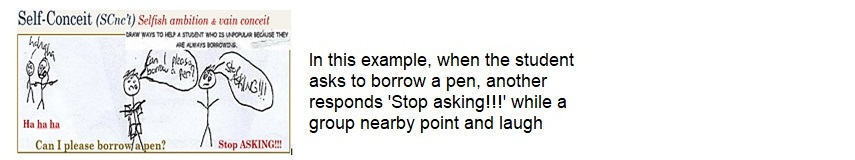

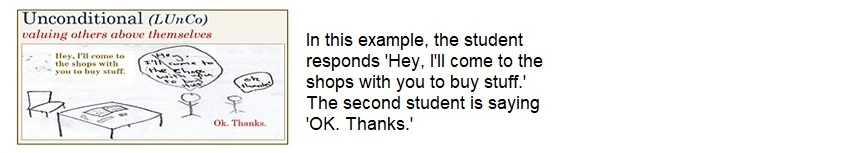

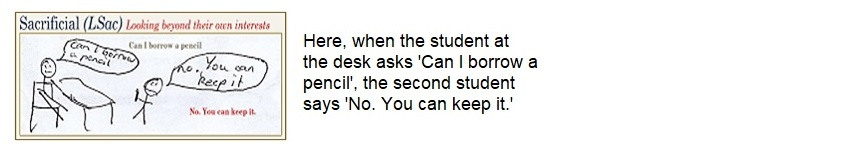

For example, in a Borrowing Scenario from the year 5 Salience Curriculum, students were asked to ‘Draw ways to help a student who is unpopular because they are always borrowing’. Their responses included:

- Self-Conceit: vain, self-centred

- Conditional (love): valuing others not yet above their own interests

- Unconditional (love): valuing others as/above themselves

- Sacrificial (love): looking beyond their own interests

In another scenario on bystander responses to bullying, it wasn’t only what the students drew, but what was missing from the picture that was telling. For example, before PVP instruction, some students didn’t draw themselves as being part of the solution, but in the post-instruction assessment they did.

In addition to helping evaluate student knowledge and understanding at the end of a unit of work, using drawings before teaching a topic can be a good way to draw out students’ preconceptions and misconceptions.

ACER’s Research Conference 2025 takes place at the RACV City Club, Melbourne on 6 and 7 February. The theme is Transforming learning systems – enabling holistic growth for all students. To find out how you can showcase your own research, and for information on the keynotes, presenters and registration, visit the conference website.

References and related reading

Bonoti, F., Christidou, V., & Spyrou, G. M. (2019). ‘A smile stands for health and a bed for illness’: Graphic cues in children’s drawings. Health Education Journal, 78(7), 728-742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896919835581

Deguara, J., & Nutbrown, C. (2018). Signs, symbols and schemas: Understanding meaning in a child’s drawings. International Journal of Early Years Education, 26(1), 4-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1369398

Knowles, A.L. (2021). Using student drawings to evaluate change in other-focused thinking, reflecting Philippians 2:3-4. In Beverly J. Christian & Peter W. Kilgour (eds) Revealing Jesus in the Learning Environment: Evidence & Impact, 151-194. Avondale Academic Press.

Knowles, A. (2023a, May 13). Using drawings to show change in students’ propensity to be other-focused and to risk being upstanders [Conference presentation]. 2023 Research Conversations Christian Education Conference. St Andrew’s Cathedral School, NSW.

Knowles, A. (2023b, September 3-4). Student drawings: An AI-eschewed means to show curriculum-based change [poster presentation]. Research Conference 2023: Becoming Lifelong Learners. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/rc21-30/rc2023/posters/8

Miller, S. (2021, September 1). Using Drawings for Formative Assessment. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/article/using-drawings-formative-assessment/

Smith, T., & Knowles, A. (2021). Personal Viewpoints Pedagogy and counterfactual thinking: Year 7 students’ development of agency, resilience, critical thinking and fourth-person perspective. International Journal of Christianity & Education, 25(2), 215-239. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056997120966355

Tay-Lim, J., & Lim, S. (2013). Privileging younger children's voices in research: Use of drawings and a co-construction process. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 65-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200135