In The Connection Curriculum: Igniting Positive Change in Schools Through Sustainable Curriculum educational leader and doctoral student Matt Pitman explores the role of connection in fostering students’ academic achievement and wellbeing.

The book takes a closer look at understanding connection, and how teachers, leaders and community members can build sustainable practices and maintain this connection over time. This exclusive extract for Teacher readers comes from ‘Chapter 1 The connection journey’, and focuses on one of 3 key landmarks – meaning.

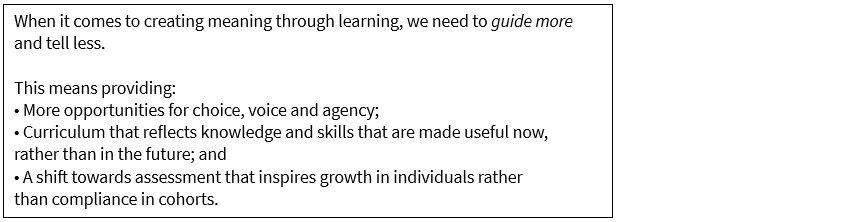

What do you want to be when you grow up? is a question designed to inspire children to be curious and imaginative. This, however, is not meaning, yet it is how we treat meaning in our schools. We need to shift our thinking from questioning what do you want to be, to who do you want to be. Meaning in education needs to be less about the future and more about the here and now. Deep and meaningful connection with others allows us to truly know ourselves.

Schools must shift to developing a focus on assisting young people to know themselves outside of the measurable qualities a degree or a career may require. Educators are spending more and more time building relationships and attempting to learn about their students and, as discussed in Landmark 1: relationships, this holds immense value at the beginning of the connection journey.

The question is this, however, do we, in education, push the students to get to know who they are, what drives them and what they value beyond what feeds the prescribed curriculum or to a depth beyond the superficial? Do we genuinely collect this information for the student to utilise personally or is its primary value in narrowing course selection and pathways options?

Students certainly need to feel as though they have a teacher that knows them and understands their needs (Allen et al., 2018), but not at the cost of knowing this for themselves.

We ‘handhold’ a lot in education these days, and societal pressures are increasing this phenomenon. A student cannot come to terms with their own meaning without an understanding of who they are and what they are capable of (Rui & Liu, 2023).

When schools do not prioritise connection to the self early, all students are at a greater risk of poor decision-making and increased risk-taking in the future, driven by feelings of social isolation and of hopelessness (Biag, 2016; Peng et al., 2023).

This is a direct disconnect from meaning and provides enormous challenges for schools, especially when a lack of meaning becomes a survival skill. Feelings of hopelessness can quickly become a learned series of behaviours, initiating the flight, fight, freeze response designed to assist the young person to survive in an environment that may be perceived as unimportant, threatening or not safe (Morton, 2022).

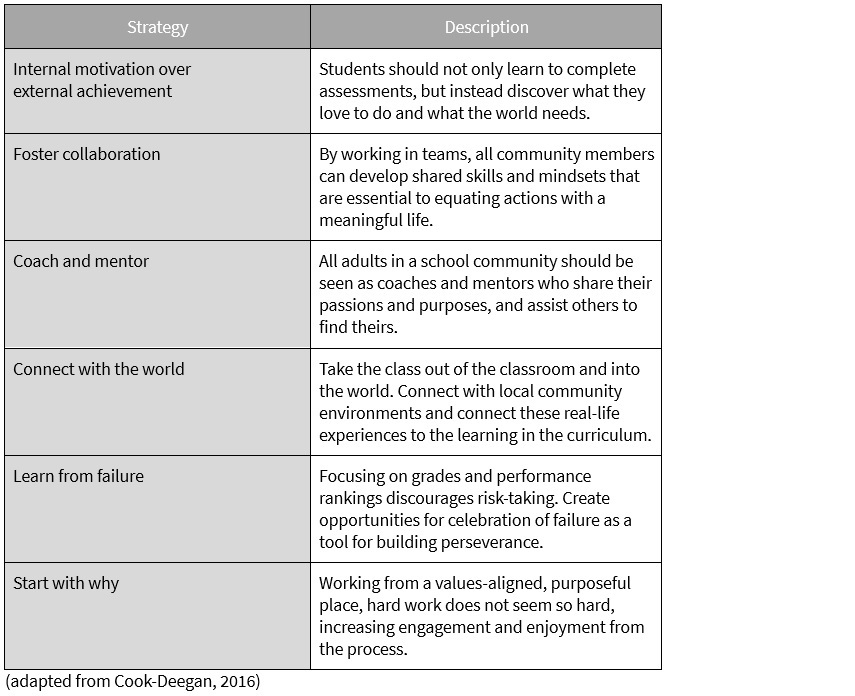

This is, unfortunately, not an uncommon perspective when questioning students on their experiences at school. A young person’s meaning within a classroom should not simply be reduced to survive to the bell. When it comes to educating a young person, schools are in a pivotal position and are incredibly influential in building not only critical and creative thinking, as well as literacy and numeracy skills, but self-sufficiency, empathetic competence and interpersonal relatedness to those around them (Carney et al., 2017). In Table 4 below you will find some simple strategies for developing community meaning.

Table 4: Strategies for creating a sense of meaning

Our approach to developing a sense of meaning must be expanded to emphasise and create opportunities for the development of the intrapersonal understanding required for young people to know who they are, not just what they could be.

The Connection Curriculum: Igniting Positive Change in Schools Through Sustainable Connection by Matt Pitman, published by Amba Press, is available to order now via the link.

References

Allen, K.A., Kern, M.L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What Schools Need to Know about Fostering School Belonging: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 1–34.

Biag, M. (2016). A Descriptive Analysis of School Connectedness: The Views of School Personnel. Urban Education, 51(1), 32–59.

Carney, J.V., Kim, H., Hazler, R.J., & Guo, X. (2017). Protective factors for mental health concerns in urban middle school students: The moderating effect of school connectedness. Professional School Counseling, 21(1).

Cook-Deegan, P. (2016, January 11). Seven Ways to Help High Schoolers Find Purpose. Greater Good Magazine. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/seven_ways_to_help_high_schoolers_find_purpose

Morton, B.M. (2022). Trauma-Informed School Practices: Creating Positive Classroom Culture. Middle School Journal, 53(4), 20–27.

Peng, A., Patterson, M.M., & Joo, S. (2023). What Fosters School Connectedness? The Roles of Classroom Interactions and Parental Support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–12.

Rui, Y., & Liu, T. (2023). The effect of online English learners’ perceived teacher support on self-regulation mediated by their self-efficacy. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras, (40), 215–233.

As an educator, when was the last time you spoke to students about who they are, what drives them and what they value (beyond the requirements of school)?

Look at the table from this extract – which shares 6 strategies for creating a sense of meaning. With a colleague, or group of colleagues, choose one of the 6 to bring into your own practice over the next term.