The power of professional judgement

Teacher is delighted to welcome Professor Martin Westwell as a regular columnist. In his first article, the Chief Executive of the South Australian Department for Education discusses a worrying trend in Australian education, and PISA 2022 evidence that ‘our greatest strength in education is the professional judgement of our teachers’.

There’s a worrying trend happening in Australian education at the moment. It exploits people’s desire to group ideas into categories. There’s often a ‘right’ category and a ‘wrong’ category, followed by an argument about whose ‘right’ is best.

Creating false dichotomies and asking people to take sides is nothing new, but I am concerned that asking teachers to believe in one dogma or another – rather than think about the ultimate goal of what will make the biggest difference for their students’ learning and development – deprofessionalises them.

The latest example is the schism between explicit direct instruction (EDI) and other approaches to teaching. I saw a comment recently on social media, lamenting South Australia’s so-called ‘decline back to constructivism’.

A combination of tools to support learners

This notion that teachers should either be directly instructing students or getting students to do the thinking and construct their understanding seems nonsensical to me. Teachers have a range of tools in their toolkit, the trick is using the tools in a combination of ways so that each learner has the teaching and support they need to effectively learn.

EDI is important; it’s fundamental when introducing new information and developing skills. For example, many of the building blocks of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and oral language) require a high degree of instruction and practise. Children won’t reason their own way to mastery of phonics without instruction, and there are well established evidence-informed ways of going about this.

Every child and young person is a complex being, and while their learning and development take similar trajectories, each is influenced by factors unique to them. This web of factors can make it difficult to isolate the specific influence of different experiences. Direct instruction of knowledge and skills is right up there and highly influential (for example, Rosenshine, 1986); John Hattie helped us to understand the value and nature of impactful feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007); and the UK Education Endowment Foundation’s metanalysis demonstrates the enormous difference that can be made to student performance through strategies to develop their metacognition and self-regulation (Education Endowment Foundation, 2023).

Students’ sense of belonging

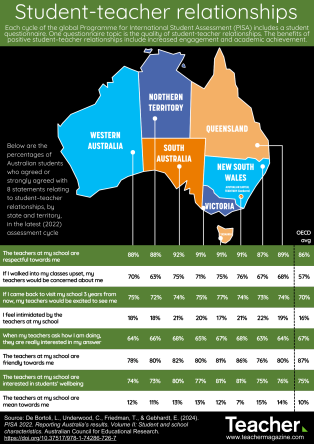

The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) can give us some insights, too. Not only does this international comparison of 15-year-olds give us information about students’ performance in reading, science and mathematics, it also reports other factors that can influence learning – such as experience of bullying, a sense of belonging, and metacognition.

The core assessment domain for the 2022 PISA test cycle was mathematics, and in Volume II of the Australian report (De Bortoli et al., 2024) we find an analysis of those school and student factors. Let’s focus on students’ sense of belonging at school.

The Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) analysis compares the mathematics performance of students who are in the lowest quarter in terms of sense of belonging with the mathematics performance of those in the highest quarter. We see that there is a 26-point difference in mathematics performance between those students with the lowest level of belonging and those with the highest.

But what does 26 points mean? For comparison, it is worth noting the difference between the 10th and 90th centile for Australian mathematics performance is 261 points, so the difference associated with belonging is about 10% of this. Another way to get a feel for the size of this difference is relative to the gap of 88 points between Australia’s results and those of perennially top-performing Singapore.

Of course, the relationship between a sense of belonging and mathematics performance is a complex one and causation is difficult to establish. For example, it’s conceivable that a sense of belonging has an impact on performance but also that performance improves students’ sense of belonging. Most likely it runs both ways.

Other research gives us confidence that there is something of a causal relationship between wellbeing and performance. For example, in 2022 researchers from the Australian National University and Gradient Institute (Cárdenas et al., 2022) demonstrated that students with greater wellbeing in year 8 are more likely to have higher academic scores 7-8 months later when they take the NAPLAN tests. Importantly, they reported ‘This effect emerges while also accounting for previous test scores and other confounding factors’.

So, it seems that it would be useful to consider students’ sense of belonging when thinking about ‘What would have to be true for our students to learn effectively and perform in standardised tests scores?’ What else can we learn from PISA 2022?

Teacher support and positive relationships

The extent to which students report teacher support is also explored in the Australian Volume II report. ‘Australian students in the highest quarter of the Teacher support index scored 44 points higher than Australian students in the lowest quarter of the index,’ (De Bortoli et al., 2024). This is an even more complex construct than belonging – students’ perception of the support they get from teachers might be different from the actual level of support. Nevertheless, the performance of students reporting the highest level of teacher support is unsurprisingly much higher than that of those reporting the lowest levels of support – similar to half the gap between Australia and Singapore.

A positive relationship between students and a teacher (or adult at the school) often shows up as an important factor in student wellbeing, and here again we see a relationship with mathematics performance We see its connection to mathematics performance, with students in the highest quarter of this measure scoring 59 points higher than those in the lowest quarter.

For some schools seeking to improve mathematics results it may be worth considering these relationships as well as the nature of classroom instruction.

I find these data fascinating. They do not give us certainty around what exactly should be done to improve the mathematics performance of students, but they give me pause for thought about how to best complement current instructional practices. It makes me think about how we might best support the choices teachers make in their specific contexts and the toolkit of practices they need available to them.

Perseverance and curiosity

There are more factors covered in PISA, and I have saved the best until last. The constructs in the survey related to the largest differences in performance are perseverance (61 points) and curiosity (at a whopping 81 points). As we can see, the performance gap between Australia and Singapore is similar to the difference between our own least and most curious students.

Returning the question of ‘what would have to be true for our students to learn effectively and perform in standardised tests scores?’, it seems that in addition to the exceptionally important EDI that they need, wellbeing, perseverance and curiosity are among a range of incredibly important factors. These factors can be changed for better or worse by the experience students have in the classroom.

Not only are these factors important for performance in mathematics tests, they are also important for life beyond the classroom. Employers and universities told us as much during consultation when setting our strategy for public education in South Australia (Department for Education, 2023).

School leader experiences

We can also gain qualitative evidence and insight by listening to people’s stories. One R-12 school principal was rightly proud of the improvement in NAPLAN and year 12 results they achieved by focusing on EDI but told me how disappointed she was when local businesses were not employing her graduates. They told her that the students’ literacy and numeracy skills were great, but that the students from her school didn’t make very good colleagues and so were not so employable. She rebalanced her approach and now the employers are knocking at her door while maintaining good results.

A primary school principal had a similar experience when the high schools that enrolled her students fed back that while their foundational literacy and numeracy skills were much better than they used to be, the students found it difficult working in groups, problem solving and grappling with productive struggle.

The more we characterise the complex work of educators as either/or, the less sophisticated we will be, and the less well prepared our young people will be to thrive and learn in a more complex, demanding, and frankly meaner and individualistic world than we have ever known.

For me, the PISA 2022 analysis provides convincing evidence that our greatest strength in education is the professional judgement of our teachers and their ability to understand ‘what would have to be true for the children in their class to learn and achieve, thrive and prosper?’. Let’s make sure they are equipped with all the pedagogical tools they need to exercise their judgement effectively.

References

Cárdenas, D., Lattimore, F., Steinberg, D., & Reynolds, K. J. (2022). Youth well-being predicts later academic success. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 2134 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05780-0

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., Friedman, T., & Gebhardt, E. (2024). PISA 2022. Reporting Australia’s results. Volume II: Student and school characteristics. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-726-7

Department for Education (2023). What we heard. Strategy for Public Education, Department for Education, South Australia. https://www.education.sa.gov.au/docs/ce-office/purpose/purpose-statement-data-analysis-what-we-heard.pdf

Education Endowment Foundation (2023). Teaching and Learning Toolkit. Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/teaching-learning-toolkit.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Rosenshine, B. V. (1986). Synthesis of research on explicit teaching. Educational leadership, 43(7), 60-69.