Findings from an action research project in three West Australian schools suggest the use of quality mentor texts when explicitly teaching how to write narratives can improve students’ storytelling ability. Here, Ron Gorman and Dr Sandy Heldsinger share more details about the teaching and assessment strategies used, and samples of student writing.

‘Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.’

Whilst there is some dispute over whether Anton Chekov ever wrote to his brother advising him to describe the ‘glint on the broken glass’, this advice succinctly captures the essential craft of narrative writing. Here we would like to share with you research we undertook examining the effectiveness of using quality children’s literature as the springboard for explicitly teaching students how to create stories, how to portray characters and use a conflict to drive their story, and how to manipulate language to engage their reader.

Our overarching purpose was to explore a way of teaching that engendered more creativity in students’ storytelling. Whilst the use of mentor texts is not necessarily an innovative approach to teaching writing, it seemed to us that it may have slipped from teachers’ suite of teaching strategies.

As readers will know, one the challenges for teachers in undertaking action research arises from the complexity of collecting and analysing data to evaluate the effectiveness of the approach or method being investigated. We used the Brightpath assessment and reporting software. The assessment process enables teachers to reliably (consistently) assess students’ writing over time, easily compare pre-test and post-test data, and thus evaluate student growth in learning. The reports provide detailed learning progressions for narrative writing. In effect, Brightpath served two purposes: it provided information about what teachers need to teach their students next based on how they assessed their students, and it provided a way of collecting data that allowed teachers to evaluate the success of their innovation.

The Association of Independent Schools of Western Australia (AISWA) developed a series of resources that built upon the Brightpath reports and learning progressions to help teachers use recognised children’s literature as the foundation of their narrative writing program. These resources provided explanations and strategies to support teachers in using quality children’s literature to explicitly teach their students’ point of need in ways that are engaging and encourage students to be creative.

The resources used the writing of Sally Rippin, Morris Gleitzman, Andy Griffiths, Mark Greenwood, Ursula Dubosarsky (to mention just a few), as well as the works of illustrators such as Frane Lessac and Shaun Tan. By way of example, for the teaching point ‘teach students to provide imaginative or reflective elements (humour, drama, suspense, sympathy), a scene was identified in Morris Gleitzman’s Toad Rage – ‘the underpants scene’ – that teachers could use to show students how the author used verbs, similes, metaphors, juxtaposition and exaggeration to create humour. The resource suggested activities to give students an opportunity to explore incorporating humour in their writing, such as the suggestion to ask students to write a humorous short passage from the perspective of a flea.

Participating teachers were invited to attend a full-day workshop in which they not only had the opportunity to work through and discuss the resources, but also heard from WA author Mark Greenwood and illustrator Frané Lessac about how they researched and crafted their work.

Three teachers from three different schools participated in the full action research program. They asked their students to write a narrative and then scored their students’ performances using the Brightpath narrative writing scale. They used the Brightpath performance descriptors and teaching points and the AISWA resources to plan and implement their teaching program.

It should be noted that none of the materials served as a blueprint or template for how teachers were to teach writing, and teachers were free to use their professional knowledge to design their lessons and activities. They implemented their teaching programs over about a term and then reassessed their students. All three saw a dramatic improvement in their students’ writing results.

It is hard to convey all the different ways that these teachers used literature to teach writing and we share just some of their work here.

Julia Creasy, from Carmel School in Perth, chose to use Hey Jack and Billie B Brown by Sally Rippin, with her Year 1 class because the books tell simple but engaging stories. In particular, Creasy liked the inclusion of experiences and conflicts typical to her students’ lives and thought that these would be an excellent foundation for helping her students understand how they could draw on their own experiences to craft their stories. Teaching activities included talking with her students about how the characters in Hey Jack spoke to each other and what that revealed about them and their relationships. She used speech bubbles to explain to students how they could write short interactions between characters and she taught them how to write dialogue for a puppet play. All the time Creasy was teaching her students to think about what one character says to another and how they can use dialogue to reveal characters and to tell their story.

She also spent time with the class discussing and analysing the characters’ moods and the ways the author conveyed her characters’ emotions. She reported that Rippin’s books led to great discussion and the students never tired of rereading and talking about the books. She also showed her students how to compare and contrast their own character traits with those of characters in the story.

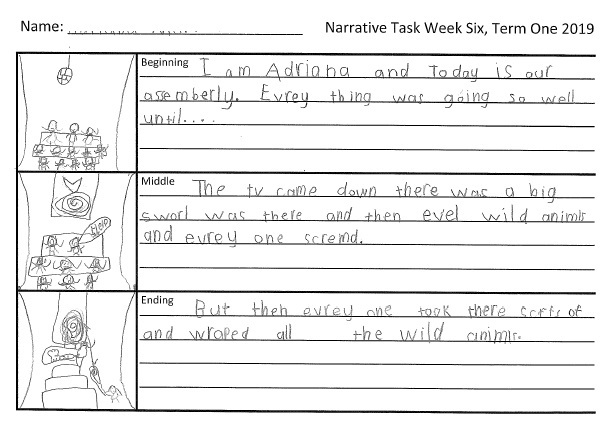

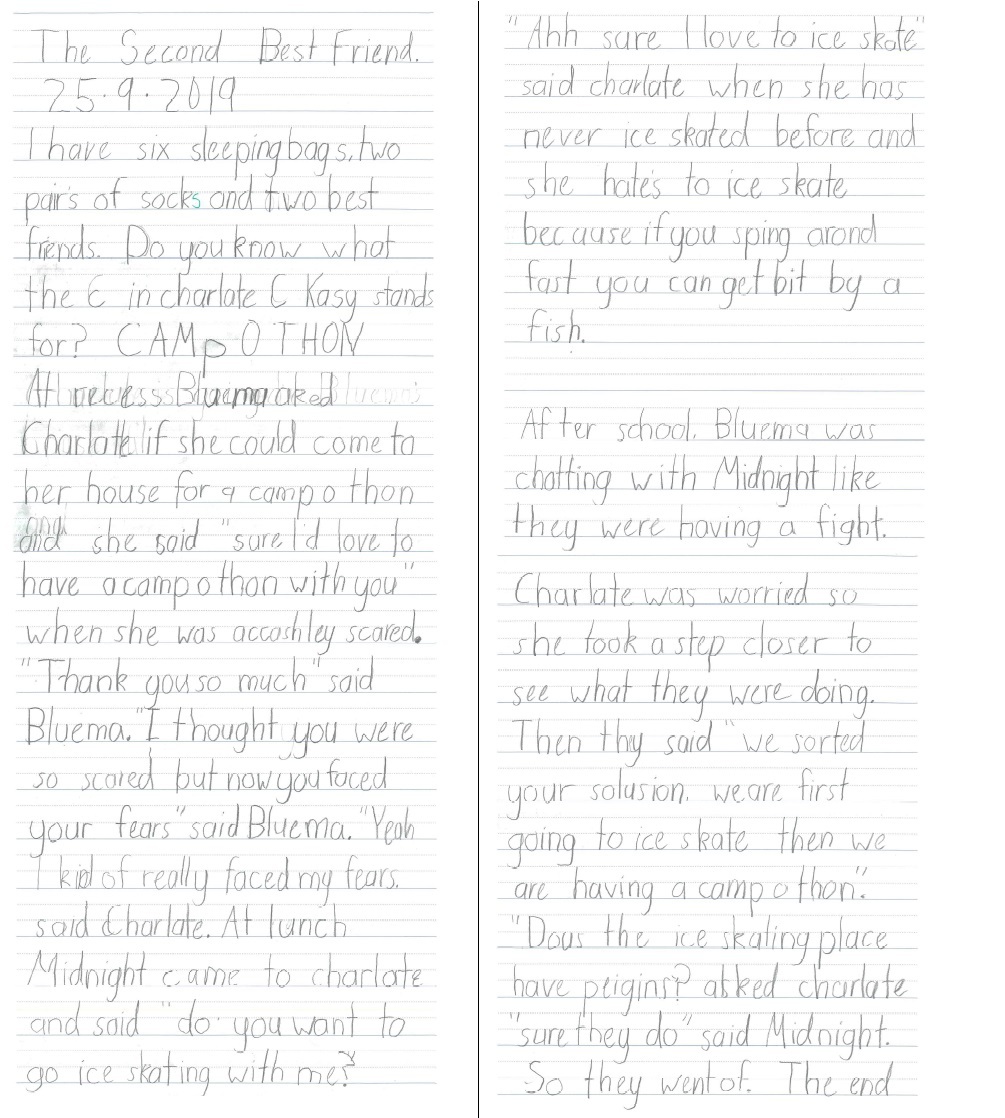

After explicitly teaching her students how to think about setting up a problem or conflict and how to resolve the problem, she felt they were ready to write a second narrative. She set parameters for their story and encouraged them to use Rippin’s structure as a guide. The students had to locate their story within the school or classroom setting and were required to include themselves as a character; they also had to include a best friend and second-best friend in their story. The problem in their story had to be based on possession and friendship and the resolution needed to be based on sharing and including others.

Pre- and post-test data were collected for 28 students. The mean performance increased by 62 score points on the Brightpath scale between Term 3 and 4 (195.5 and 257.5, respectively). This can be compared to the ‘All schools’ mean for Year 1 in 2020, which increased by 20 score points in the same period. Whilst the statistics are important, the evidence of improvement in the students’ writing samples is heartwarming. The example below shows the pre- and post-test performances for a student who made particularly marked progress over the term.

Student 1: Pre-test performance, Term 1, Score 230

Student 1: Post-test performance, Term 2, Score 410

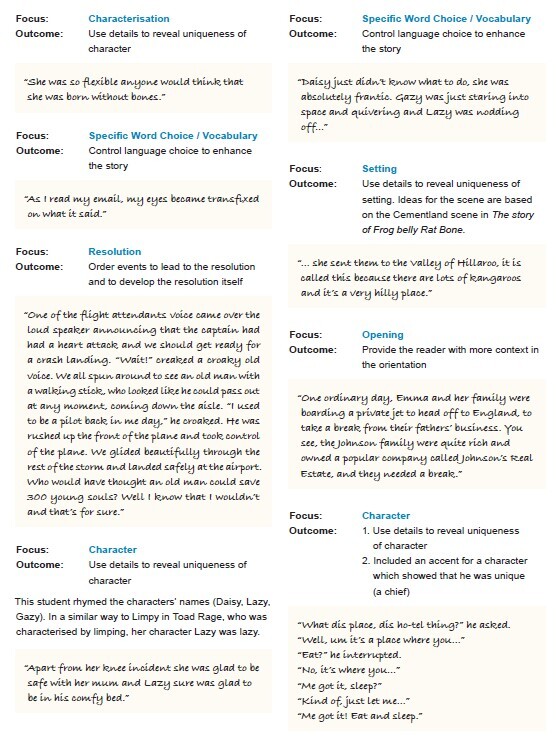

Evelyn Temmen from Trinity College, Perth, decided that Toad Rage by Morris Gleitzman and The Story of Frog Belly Rat Bone by Timothy Basil Ering would engage and inspire her Year 4 students and would act as excellent mentor texts when teaching them how to play with language and develop their storytelling techniques. She used the literature to teach her students how to manipulate sentences and play with word order to convey character in just a sentence or two. Activities engaged students in much discussion about how they could use descriptive and precise language to engage their reader. Temmen found Toad Rage particularly valuable in teaching her students how authors reveal setting through dialogue and actions and how they convey humour and emotions.

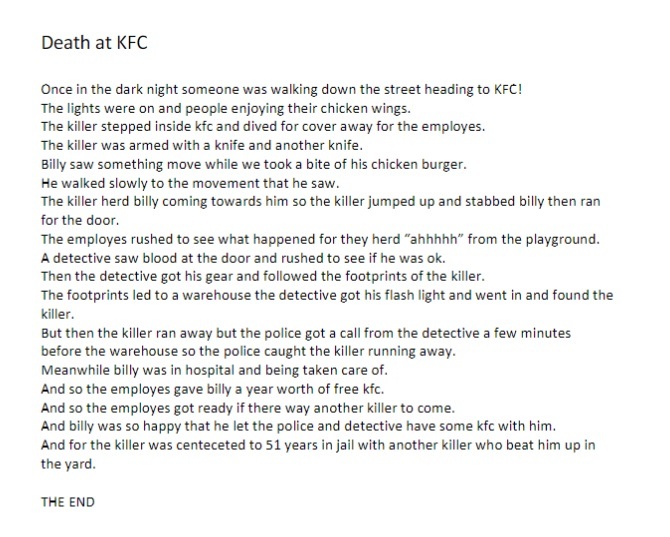

Twenty-four students completed the pre- and post-test assessments and means improved by 30 score points between Term 2 and 4 (295.6 and 325.8 respectively), where the ‘All schools’ mean for Year 4 between Term 2 and 4 increased by 13 score points. The example below illustrates how a student applied his learning from the mentor texts to incorporate descriptive words and phrases effectively, especially in his orientation.

Student 2: Pre-test performance, Term 2, Score 280

Student 2: Post-test performance, Term 4, Score 370

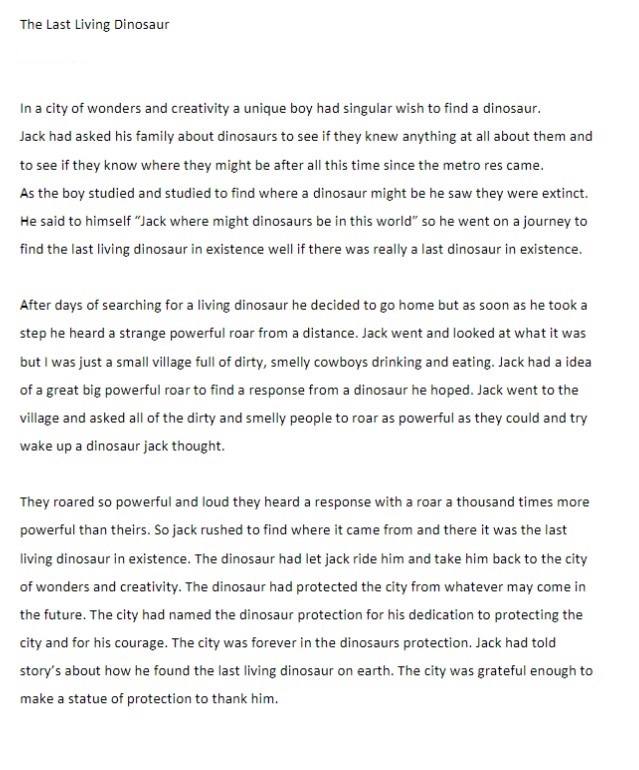

Rachel Pendal from Kalamunda Christian School, also in Perth, analysed her students’ pre-test performances and identified that she needed to focus on improving writing fluency, extending their vocabulary and word choice, teaching them how to craft their descriptions of character and setting and teaching them how to develop their complication and then resolve it. She also recognised that she would need to differentiate her teaching to cater for the different ability groups in her class.

Pendal planned a five-week program of three one-hour lessons focused on writing instruction. She also planned to integrate her teaching of writing in two 30-minute lessons per week on grammar and two one-hour lessons per week teaching reading. As well as using texts suggested by AISWA, she drew on an extensive range of books for different lessons. For example, she used The Invention of Hugo Cabret (by Brian Selznick), Doubting Thomas and Once (Morris Gleitzman), How to Bee (Bren MacDibble), The One and Only Ivan (Katherine Applegate) and Charlotte’s Web (E.B. White) to show her students how authors create story openings that engage the reader and to set the scene. She used The Indian in the Cupboard (Lynne Reid Banks) to teach her students new vocabulary and how to incorporate figurative language in their writing and Toad Rage to help them think about playing with perspective and incorporating humour in their writing.

The following examples taken from her post-test performances illustrate how students applied what they had learnt from the literature to their own writing.

All three teachers observed that their middle and high-achieving students benefited greatly from the approach taken. Interestingly, all three observed that their low-achieving students did not benefit to the same extent.

The action research was rerun in 2020 with a larger group of teachers from all three school sectors. Like those in the first round of the project, the teachers in the second saw marked improvement in their students’ writing. The initiative seemed to work for students of all ability groups in the second round – it could have been that these teachers had learnt from the first group and ensured their intervention catered for all abilities in their class. We did not survey students, but all teachers reported high levels of student engagement and enjoyment.

The findings from our action research suggest that a combination of the use of literature as the basis for teaching narrative writing and well-supported formative classroom assessment can lead to marked improvement in students’ storytelling ability, even over short periods. Given the success of the program, AISWA is creating a short, guided course that schools can follow themselves, and these materials will be made available to schools later this year.

We would like to acknowledge and thank Julia Creasy, Evelyn Temmen and Rachel Pendal for participating in the research project and the dedication their brought to the research. We would also like to acknowledge Penny McLoughlin who conceptualised and developed the resources used in the research, and who shared her expertise so openly with all participants, and Kerry Handley and Ana Lisa Randal who coordinated the project and made everything happen.

Related reading

Heldsinger, S.A (2021, May 21). Teacher moderation that contributes to effective teaching. Brightpath https://www.brightpath.com.au/articles/teacher-moderation-that-contributes-to-effective-teaching/

Heldsinger, S., & Humphry, S. (2010). Using the method of pairwise comparison to obtain reliable teacher assessments. The Australian Educational Researcher, 37(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216919

Heldsinger, S. A., & Humphry, S. M. (2013). Using calibrated exemplars in the teacher-assessment of writing: an empirical study. Educational Research, 55(3), 219-235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.825159

Humphry, S., & Heldsinger, S. (2020, February). A two-stage method for obtaining reliable teacher assessments of writing. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 5, p. 6). Frontiers. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00006

What strategies and materials do you use to support your teaching of narrative writing and to be more creative in their storytelling?

Have you ever considered using mentor texts? Thinking about your own students, which texts and authors would you choose and what would be your improvement focus?