Personal fitness trackers and smart devices that log our daily steps and monitor our heart rate have increased in popularity in recent years. This kind of portable, wearable technology is also being used by researchers in the classroom to gain insights into how the brain learns.

Professor Ross Cunnington is a Chief Investigator at the Science of Learning Research Centre (SLRC) – an Australia-wide collaboration bringing together researchers from the fields of education, neuroscience and cognitive psychology.

His study with fellow SLRC Chief Investigators Professor Robyn Gillies and Professor Annemaree Carroll into small group cooperative learning uses wearable technology to collect data in a classroom environment. ‘We're trying to provide an evidence base for education practice based on what we know about how the brain learns,' Cunnington tells Teacher.

In 2014 the first phase of the study focused on Year 6 science lessons and involved eight teachers and approximately 200 students from three schools. Measurements of temperature, heart rate, movement and skin conductance were collected using Empatica E3 wristbands.

‘It's a research device [they're quite expensive], but the company also has a more off-the-shelf band for about $200 which they're hoping to develop for alerting people with epilepsy to potential oncoming seizures,' Cunnington explains.

Although the wristbands used in the study have the look of a fitness tracker, the key difference is their ability to measure skin conductance (sweating response). ‘There are a few names for it – it's electro dermal activity – but it changes with sweating of skin. It's caused by part of the brain stem. When physiological arousal increases people sweat more; when it's very high that's when you're anxious and stressed, when it's very low that's when you're really bored or sleepy. The middle range is where people perform optimally – alert and engaged.'

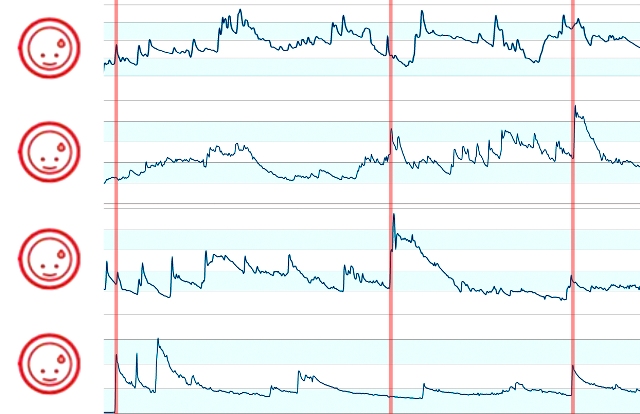

The research team is interested in small group interactions. Cunnington says they're looking for synchrony in the wristband data – students who respond in the same way at the same time. Other members of the team are exploring language use and social negotiation.

Kelsey Palghat, a Senior Research Technician in the Cunnington Lab, says the big advantage of wearable devices is being able to work with students and teachers in their real classroom.

[Skin conductance measurements from four children. The red markings highlight where some students show a similar response. Image: Supplied]

Last year, the second phase of the study focused on Year 7 science lessons at four schools, involving nine teachers and approximately 325 students. They wore the upgraded E4 wristband model and another wearable technology – sociometric badges. ‘They're from a company in the US, actually developed by a research group and largely around business,' Cunnington says. ‘So, they've been used a lot in office workplaces … [looking at] social interactions between workers around boardroom tables and things. They measure proximity to other badges, other people.

‘[The badge hangs] on a lanyard around the neck. It's about the size of a credit card and it measures proximity to other badges. So, as people are moving around in the space you can track who they're close to at any time. It detects their speech – it doesn't record what they say but it gives statistics about how much time people spend talking and how much time they are talked to.'

The team is also using the SLRC's Learning Interaction Classroom in Melbourne, collecting wristband data alongside audio and video recordings. ‘It gives us an incredible opportunity,' Cunnington says. ‘On the wristbands we can look for events when a whole group around the table or whole class come into synchrony … and you can pinpoint that time and then go back to the video and the audio and start to investigate what really happened in the class at that time.'

The SLRC is funded by the Australian Research Council and is led by a consortium of researchers from the Queensland Brain Institute, University of Melbourne and the Australian Council for Educational Research.