Why children with disabilities deserve better

I have always believed that everyone deserves a quality education. In fact, that was the motivating ideal that led me into politics. It shaped my purpose and priorities as Prime Minister, and continues to drive me in the causes I champion post-politics.

One of those is in my role as Chair of the Global Partnership on Education (GPE), which has a clear mission to ensure every child has the opportunity to go to school. GPE works in Partnership with almost 70 developing countries to improve their education systems.

To support this work, GPE recently held a Funding Replenishment Conference in Dakar, Senegal. Under the banner of the UN's plan for sustainable development, this was a key opportunity to bring together world leaders, civil society, private foundations and enterprises, in demonstration of a commitment to the common goal of education for all.

The conference was highly successful, with donor governments and foundations committing an unprecedented $2.3 billion dollars to fund GPE's work over the next three years.

The efforts of GPE to date has meant 72 million more children are enrolled into primary school in GPE partnered countries in 2015 compared to 2002. The completion rate of primary school has also increased, with 76 per cent of children in GPE partnered countries completing school, compared with 63 per cent in 2002.

Despite these achievements, there is still one group being left behind from all this progress. Children with disabilities.

The scale of the challenge

It is estimated that around the world, between 93 and 150 million children are living with a disability (UNESCO, 2015) and approximately 80 per cent of those children are living in a developing country. It's not hard to imagine why that number is so high. A lack of access to the basics like clean water, nutritious food and shelter take their toll. These risk are then compounded by a lack of proper medical care. War, poverty and famine cause harm in many tragic ways, including by increasing the incidence of disability.

A recent study undertaken by the World Bank and GPE (Male & Wodon, 2017) has found the gap in education between children with a disability compared to those without is getting bigger. The problem is even greater for females with a disability. We simply cannot allow this to continue.

We know that people with disabilities have an enormous amount to contribute to their communities and to society, if only given the opportunity. We also know that their persistent exclusion from school has devastating long-term consequences, with only 3 per cent of adults with a disability in the developing world having achieved basic literacy.

The heartbreaking reality is that much of the problem is still invisible. Currently, governments are struggling to quantify the depth of the problem because adequate data on children with disabilities does not exist. Without robust data, governments can't understand the needs of children with disabilities, and what stands in their way to getting the education they deserve.

In fact, it is estimated that around 90 per cent of children with a disability are not even enrolled in school (UNICEF, 2014). Some of this may be because schools aren't properly equipped to accommodate them. But it can also be because concerned parents are afraid of how their child will be perceived, or perhaps want their child to avoid negative experiences at school.

Denying children with a disability the chance to go to school only further reinforces the stigma and discrimination they will face for the rest of their lives. It denies them the opportunity to understand and participate in the world around them, to advocate for their needs, and influence their community to become inclusive for people with a disability.

Programs supporting teachers and students

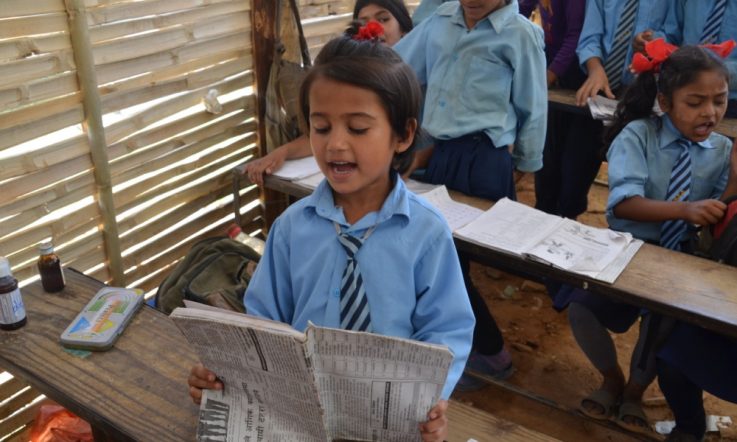

This is why one of the dedicated focus areas of GPE is children with disabilities, and we are working hard to ensure disability is no obstacle to an education. In addition to working with governments to more accurately capture data that will reflect the current situation, GPE has programs in several developing countries that are helping to make learning inclusive for all.

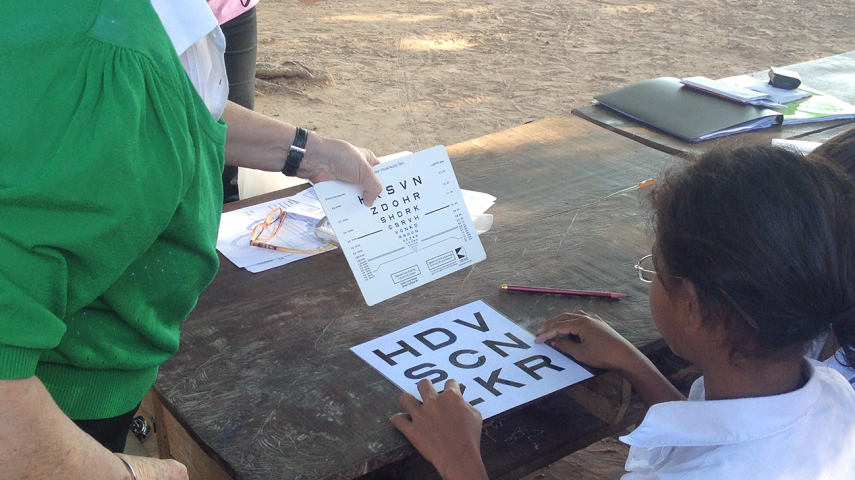

In Cambodia, a pilot project to help children with low vision is currently being supported by GPE and other partners. Teachers are given training to use vision screening kits to test the eyesight of children in school and identify any problems. If children aren't able to pass the eye exam, they are then referred onto a local health clinic for further testing, where they can be provided with eye glasses. As a result of this program, approximately 13 000 students in 56 elementary schools in Siem Reap were tested and the project is now going to be expanded with further funding through GPE.

‘Teachers are given training to use vision screening kits to test the eyesight of children in school and identify any problems.' ©GPE/Natasha Graham

Challenging stereotypes and changing perceptions of people with a disability in order to make learning truly inclusive has been the focus in Zanzibar. Safe play areas are being established in pre-primary schools, and by acknowledging that ‘one-size-fits-all' is not the best approach, teachers are being given special training to reshape the way they include and respond to the needs of children with disabilities in the classroom. There is also special equipment being provided with learning material, such as glasses, white canes, and braille machines to support children through their learning.

In Eritrea, in partnership with GPE, the government has launched a pilot program in order to discover how best to equip teachers with additional skills. To inform this work, a classroom in the Daerit Elementary School in Asmar has been established to accommodate 40 children with a range of disabilities. This classroom can be used as a testing ground for teaching techniques that can then be further expanded to other schools. GPE has also been able to support the construction of special needs classrooms.

While there are huge variations across the world in the kind of support and funding children with a disability require, ultimately there is a universal challenge which remains constant in classrooms across the world – acceptance and inclusion.

Solutions to overcoming some of the barriers to education can be quite practical – the provision of a mobility aid to get a child out the door and off to school, a pair of glasses to see the blackboard, a hearing aid to hear the teacher speak.

Or it can be less tangible – challenging old stereotypes about what a child with a disability has to offer the world. Shifting long held and deeply entrenched attitudes within communities, governments and institutions, in many ways, is a more difficult battle to fight. That's why overcoming the disproportionate exclusion of children with disabilities will take a sustained global effort. These children deserve better, and we owe it to them to do more.

References

Male, C. and Q. Wodon (2017). Disability Gaps in Educational Attainment and Literacy, The Price of Exclusion: Disability and Education Notes Series, Washington, DC: The World Bank. Accessed https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/disability-gaps-educational-attainment-and-literacy

UNESCO GMR (2015). Education for All 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges. Accessed http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002322/232205e.pdf

UNICEF (2014). Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children: South Asia Regional Study. Accessed https://www.unicef.org/education/files/SouthAsia_OOSCI_Study__Executive_Summary_26Jan_14Final.pdf