We’ve called on 2 of our expert colleagues here at the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) to look at what the latest Australian research says about teaching and learning with AI, and what you can do as an educator.

In the first section Dr Tim Friedman, Senior Research Fellow at ACER and lead author of the Australian Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2024 report shares feedback from primary and lower secondary educators. In the second section ACER Research Fellow Bethany Davies looks at 3 common challenges of using AI in the classroom as reported by Australian TALIS participants, and some strategies to help address them.

The rise of AI in education in Australia

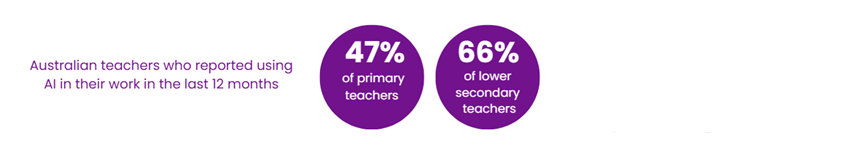

Insights from the most recent cycle of the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), show that Australian teachers are using AI more than their international counterparts (Friedman et al., 2025).

Latest findings reveal around 2 in 3 teachers at the lower secondary level and around one in 2 primary teachers reported using AI in the classroom. The data suggest it’s primarily the younger teachers who are more likely to embrace the technology.

Similar to their international peers, our teachers are most likely to be using it to learn or summarise a topic or generate lessons and plans. Compared to teachers in other countries, our teachers are more likely to use it to automatically adjust the difficulty of lesson materials according to students’ learning needs. But fewer Australian teachers are using it to support students with education needs, assess or mark student work, or review data on student performance, compared with AI-using colleagues from other countries.

Our teachers were excited about the benefits of using AI. TALIS found the majority of our lower secondary teachers believed it can help teachers to write or improve lesson plans, that the technology enables teachers to adapt learning material to different students’ abilities and that it assists teachers in supporting students individually.

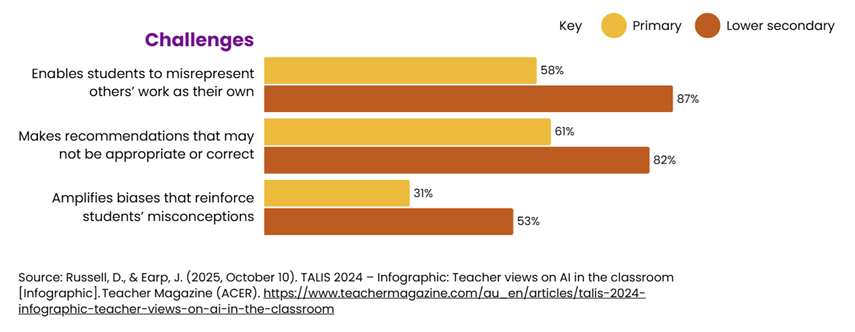

But teachers also expressed some concerns about using AI. As reported in a recent Teacher magazine infographic (Russell & Earp, 2025), more than 4 out of 5 lower secondary teachers expressed concerns that AI enables students to misrepresent others’ work as their own and make recommendations that might not be appropriate or correct. More than half also believed that it amplifies biases that reinforce students’ misconceptions.

What about those teachers who aren’t using AI? In the TALIS survey, three-quarters said that they don’t have the skills and knowledge to teach using AI. Two-fifths of teachers argued that we shouldn’t be using AI in teaching. Smaller proportions of teachers felt overwhelmed using new technologies, believed the school lacked the necessary infrastructure, or believed their school doesn’t allow the use of AI in teaching.

Insights on challenges and strategies for teachers

Let’s take a look at 3 common challenges of using AI in primary and secondary school classrooms as reported by Australian TALIS survey participants (shown in the graphic above), and some strategies to help address them.

Enables students to misrepresent others’ work as their own

The impulse to short cut effort and pass off others’ work as our own is a longstanding flaw of the human condition. This gives us a foundation from which to navigate the emerging complexities stemming from the age of artificial intelligence – particularly the profound blurring of boundaries around authorship and originality.

For example, teachers are practiced in developing innovative ways of removing the opportunity for a student to misrepresent others’ work as their own – such as formative assessments that encourage students to reflect on an issue through the lens of personal experience. By leveraging these learning opportunities, teachers (who know their students best) will notice patterns and red flags that might suggest an over reliance on artificial intelligence to produce work. It is our response to these observations that is important and I suggest we move beyond our traditional understanding of, and at times punitive reaction to, ‘cheating’ to a more nuanced, constructive and compassionate response that reflects the complexities of this moment. But what might this look like in practice?

Firstly, prevention is better than cure. It is important to acknowledge as education practitioners that this is an unchartered educational landscape that all of us are learning to navigate together. Somewhat ironically, as I write this piece, I am wrestling with the use of Microsoft Copilot to improve grammar and phrasing. Rethinking our conceptual understanding of originality against a backdrop of AI will demand an extraordinary level of skill building, and critical thinking, for ourselves and our students. It will also require a shared understanding of the boundaries that guide us, that can only be achieved through collaboration and co-design with our students.

Secondly, in some cases where there is clear evidence of deliberate use of AI to appropriate others’ work, this might represent an opportunity to reflect and consider what the student might be signalling. For example: Is the student struggling with the weight of a crowded curriculum, and high stakes assessments? Are our teaching strategies meeting the student where they are at in their learning? Does the student have a shared understanding of the boundaries surrounding their use of AI? In my experience, for most students, when given the skills, support, resources and time they need to learn and improve, the opportunity to demonstrate and showcase their intelligence genuinely lights them up and excites them – reducing the impulse to defer to the artificial kind.

Makes recommendations that may not be appropriate or correct

In my first year of high school Wikipedia launched, instantly changing how we accessed encyclopaedic information. The response from our teachers, however, was similarly swift. They emphasised the importance of critical thinking, urging us to evaluate the credibility and reliability of the information. Did this stop us from using Wikipedia? No. It did, however, disrupt our eager acceptance of Wikipedia as a source of truth.

Compared to Wikipedia, generative AI platforms such as ChatGPT, introduce a vastly more complex landscape, especially when it comes to verifying sources and algorithms that reward misinformation, and questionable recommendations. However, our response to these challenges should remain the same: continue to build the ability to think critically and illustrate the risks of disregarding these essential lessons.

I really liked this example of what this could look like in action, shared by former ACER colleague Dr Katie Richardson in a podcast special with Teacher editor Jo Earp (2025) on the topic of AI in teaching and learning.

Katie Richardson: … for example, I also know a maths teacher who uses ChatGPT to demonstrate mathematical misconceptions to students, because ChatGPT is not great with its maths.

Jo Earp: No, I’ve seen that.

KR: And so, he uses it because ChatGPT replicates, the data sources that it draws from replicate the common misconceptions in maths. So, what he does is he utilises this issue with ChatGPT to demonstrate those misconceptions to the students and help the students step through the process of rectifying those misconceptions in the AI. Now, the interesting thing is they get to the end of the process, ChatGPT spits out the right answer, finally, and then he gives it another equation that is exactly the same just with different numbers. And you know what?

JE: It can’t do it.

KR: ChatGPT can't do it. So, it's really good as teachers for us to be thinking about this in creative ways, how can we actually utilise it to help the students become more critical of what they’re seeing.

Amplifies biases that reinforce students’ misconceptions

At the core of this concern is the way AI, particularly AI-powered algorithms, ‘amplify’ our existing biases, crystalising our misconceptions of the world around us. This is a complicated problem that will require a nuanced response; however, it is my view that one of the most powerful ways forward for teachers is to similarly amplify what directly challenges our biases – that is, human connection.

Genuine human connection disrupts our biases and creates dissonance around unregulated messages we have internalised from living online. For example, in a secondary social studies class, students might be asked to research a current event using online platforms of their choice. Each student is then given the opportunity to share their understanding of the event with their peers – representing a purposeful shift from online engagement to real-world engagement with a particular issue. Through a facilitated, open dialogue, in a safe and supported classroom setting, students might quickly realise that their perspectives – shaped by personalised, AI algorithms – differ vastly from each other. This creates a valuable opportunity to spark curiosity about the drivers of this effect, and how they influence the beliefs that we hold.

But how do we create space for more human connection in schools? Interestingly, the answer might partially lie with AI. As it streamlines our work, creating the opportunity to reclaim our time, we have a chance to reflect on how we might use it effectively.

Historically, innovations designed to free time, particularly in Western culture, have not translated into increased community connection, but a relentless search for more productivity (email springs to mind), and this has also been the case in schools. When it comes to AI, this shift could be a valuable opportunity for recalibration and prioritisation of human interaction and connection.

In practice, this might look like a new teacher having the capacity to participate in more lunch time student clubs rather than desperately trying to design another lesson plan. It might look like an experienced teacher having an informal conversation with a less experienced peer about a student they are worried about in the hour before the staff meeting rather than hurriedly trying to collate the latest reading results of year 4.

In summary, the concerns expressed by teachers about the use of AI are real and valid, but they are not without precedent. Let’s continue to build on what we already know, co-design new ways of working with our students, create safe and supported learning environments to explore these challenges, get curious, create dissonance and double down on human connection.

The role of teachers to support and guide young people to live and learn in our new reality is more important than ever.

References

Earp, J. (Host). (2025, May 8). Podcast special: AI in teaching and learning [Audio podcast episode]. Teacher Magazine (ACER). https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/podcast-special-ai-in-teaching-and-learning

Friedman, T., Ainley, J., Schulz, W., & Dix, K. (2025). TALIS 2024. Australia’s Report. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-801-1

Russell, D., & Earp, J. (2025, October 10). TALIS 2024 – Infographic: Teacher views on AI in the classroom [Infographic]. Teacher Magazine (ACER). https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/talis-2024-infographic-teacher-views-on-ai-in-the-classroom

What are you doing in your classroom to help students think critically about AI-generated content? How do you tackle misconceptions and biases with your students now, and how do you think AI makes that easier or more complicated?

As a school leader thinking about planning professional development for your staff in 2026, what kinds of training or support would help teachers feel comfortable and confident using AI in their classrooms?