The latest PISA results show Australia has stemmed a long-term decline in student performance levels, but large proportions of 15-year-olds are still failing to meet the National Proficient Standard. The Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) manages PISA in Australia.

In this expert Q&A, Lisa De Bortoli – ACER Senior Research Fellow and National Project Manager for Australia for PISA – explains what the results tell us about students’ skills and knowledge, and how schools can use the data to inform teaching and learning. She also shares early findings from PISA’s student and principal questionnaires.

What is the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and what do the schools who participate do?

PISA measures the knowledge and skills of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science and reading and how well they are prepared to use these skills to meet real-world opportunities and challenges. While other international assessments such as the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) assess what students have learnt in school, PISA assesses how well students can apply what they have learnt at school.

PISA has been conducted every 3 years since it commenced in 2000. The eighth cycle, originally planned for 2021, was postponed to 2022 to accommodate the constraints that many education systems experienced because of the COVID-19 pandemic. In each cycle, the 3 subject areas are rotated so that one subject is the major focus. In PISA 2022, the major focus was mathematics, and this allows for an in-depth analysis of student performance in this area.

Around 690,000 students from 81 countries and economies, including 13,437 Australian students from 743 schools, participated in PISA 2022. These students completed a computer-based test and a questionnaire. In the test, students were asked to respond to a stimulus and a series of questions. There was a range of response formats, including multiple-choice questions and open-constructed questions, where students had to provide a written response. In the questionnaire, students were asked about their family background and their attitudes towards learning.

School principals and teachers from participating schools were also involved in PISA. They completed an online questionnaire that asked about school characteristics, the quality of the school’s teaching and educational resources, teacher training, teacher professional development, instructional practices and school and classroom climate.

How did Australian students perform?

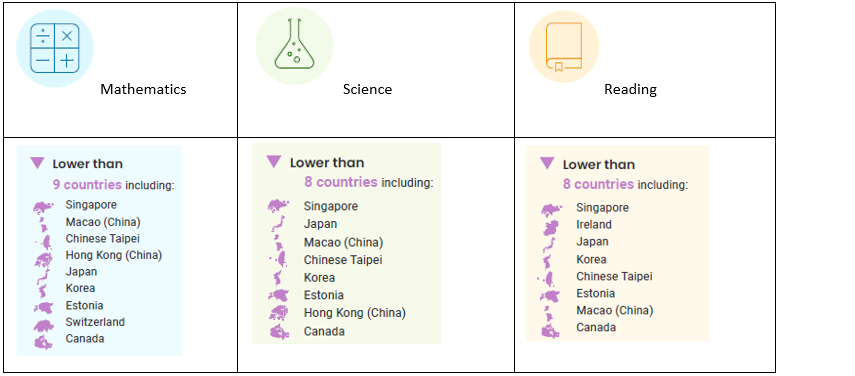

Australia’s global standing in PISA has improved since 2018. We have jumped from equal 24th in mathematics in 2018 to equal 10th in 2022. In science we’ve gone from equal 13th to equal 9th and in reading from equal 11th to equal 9th. However, this change is due to other countries’ performance declining rather than any improvement within Australia. In mathematics, there were 11 countries (including Finland, Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom) who in PISA 2018 were performing significantly higher than Australia but in PISA 2022 are on par with Australia, and there were 6 countries (including France and New Zealand) who in PISA 2018 were on a par with Australia, but in PISA 2022 are performing significantly lower than Australia.

Singapore was the highest performing country, scoring 88 points higher than Australia in mathematics, 54 points higher in science and 45 points higher in reading. For context, the OECD estimates that students learn at a rate of just over 20 points per year, meaning there is between 2- and 4-years’ difference in the achievement of Australia’s students compared to Singapore’s.

The good news is that, despite the pandemic, Australia’s performance in mathematics, reading and science has remained stable since 2018, with our maths and reading performance also similar to 2015. However, the bad news is that Australia’s overall performance has declined since the early 2000s, with on average, a 37-point decrease in mathematics, a 20-point decrease in science, and a 30-point decrease in reading. This means that, in PISA 2022, Australian students scored at a level that would have been expected of 14-year-old students, 20 years earlier.

The other bad news is that, between PISA 2018 and 2022, the gap between the top 10% of highest-scoring students and the bottom 10% of lowest scoring students widened in mathematics and science. This means that the low achievers became weaker, and the high achievers became stronger.

What does PISA tell us about students’ skills and knowledge?

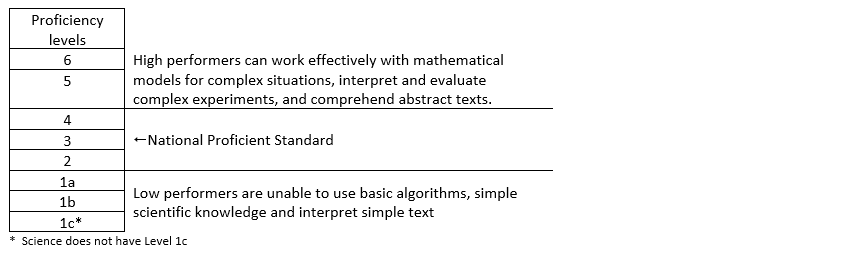

Another way of reporting PISA results is using proficiency levels. This adds a richness to the data by providing a description of what students can typically do at each proficiency level. In PISA, there are 8 proficiency levels in mathematics and reading, and 7 proficiency levels in science.

Students who attained Level 5 or 6, the 2 highest proficiency levels, were considered ‘high performers’. These students can do things like model complex situations mathematically, and select, compare and evaluate problem-solving strategies for dealing with them. In mathematics, 12% per cent of Australian students were high performers, which was significantly lower than the 41% of high performing Singaporean students.

Students who did not attain Level 2 (that is, they were placed at Levels 1a, 1b, or 1c) were considered ‘low performers’. These students are unable to do things like compare the total distance across 2 alternate routes without direct instruction or convert prices into a different currency. One in every 4 Australian students (26%) were low performers in mathematics, which was significantly higher than the 8% of low performing Singaporean students.

In Australia, Level 3 is set at the National Proficient Standard, and is the level all students should acquire by the time they are 15 years old. Students at this level are able to solve tasks that require performing several different but routine calculations that are not all clearly defined in the problem statement. They can use spatial visualisation as part of a solution strategy, and can interpret and use representations based on different information sources and reason directly from them. They typically show some ability to handle percentages, fractions and decimal numbers, and to work with proportional relationships. Fifty-one per cent of Australian students attained the National Proficient Standard in mathematics.

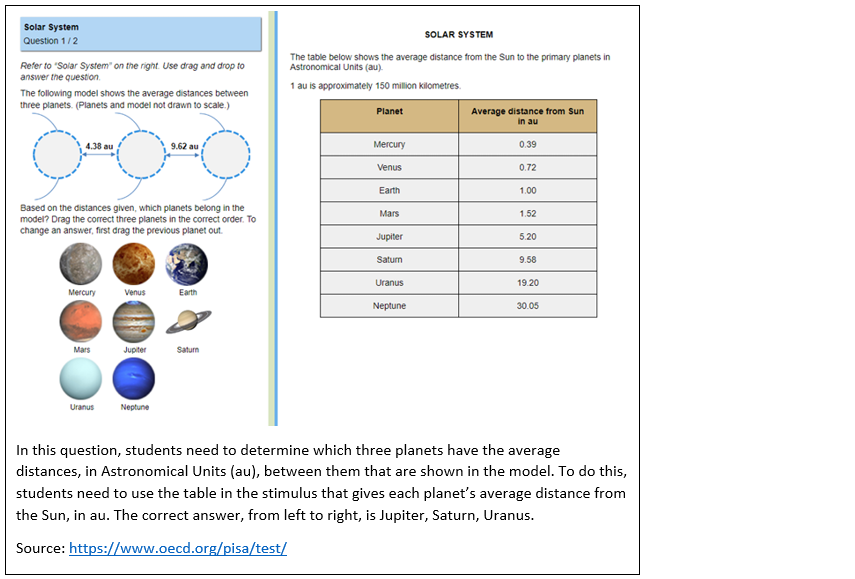

This is an example of a question placed at Level 3. The expectation, based on the National Proficient Standard, is that all Australian 15-year-olds should have the knowledge and skills to correctly respond to this question.

How can schools in Australia use PISA to identify areas of learning to address?

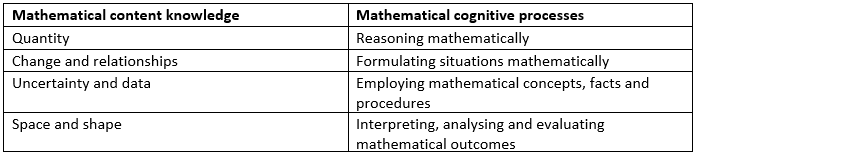

The PISA 2022 mathematical literacy framework identifies 4 content knowledge categories and 4 cognitive processes categories.

In PISA 2022, student performance was reported on 2 sets of mathematics subscales: content subscales and cognitive process subscales. On the content subscales, Australian students performed relatively stronger in uncertainty and data than on change and relationships, quantity, and space and shape, and students performed relatively higher in change and relationships than on quantity. This means Australian students performed stronger in tasks that require them to recognise the place of variation in the real world, including having a sense of the quantification of that variation, and acknowledging its uncertainty and error in related inferences. It also includes forming, interpreting and evaluating conclusions drawn in situations where uncertainty is present, as well as the presentation and interpretation of data, and basic topics in probability. So, a greater focus on the other content knowledge categories – quantity, change and relationships, and space and shape – may be warranted.

On the cognitive process subscale, Australian students performed relatively stronger in interpreting, applying and evaluating mathematical outcomes than in formulating situations mathematically, employing mathematical concepts, facts and procedures, and reasoning mathematically. This means that students at the National Proficient Standard showed a relative strength in tasks that involved using simulation results to determine a relationship between 2 contextual variables, or translating between 2- and 3-dimensional representations of solids. Again, a greater focus on the other categories may help improve Australian students’ performance and better prepare them to meet life’s challenges.

What does the student questionnaire data tell us?

The report ACER has just released focuses on how Australian students performed in PISA 2022. Our next report, which will be released in May 2024, will explore the background data for different demographic groups that was collected in the student and school questionnaires. In the meantime, we do have some national-level findings for Australian students from the PISA 2022 international report.

In PISA 2022, one quarter of Australian students reported being bullied at least a few times a month. This was a lower proportion than in 2018, although still higher than the OECD average. The results showed that, internationally on average, mathematics performance improved where bullying decreased between PISA 2018 and 2022. This finding has also been found in other studies, which also showed that lower incidences of bullying improved achievement among Australian students.

Sense of belonging at school has been measured as far back as PISA 2003. In 2022, students’ sense of belonging in Australia was lower than in PISA 2018. In 2022, the results showed that, for Australian students:

- 21% agreed or strongly agreed they felt like an outsider (or left out of things) at school

- 78% agreed or strongly agreed they make friends easily at school

- 70% agreed or strongly agreed they felt like they belong at school

- 25% agreed or strongly agreed they felt awkward and out of place in their school

- 86% agreed or strongly agreed that other students seemed to like them

- 18% agreed or strongly agreed that they felt lonely at school

One very important focus of the questionnaire looks at students’ sense of wellbeing.

School is a central part of a student’s life; when a student feels part of, and accepted by their school community, they are more likely to be actively engaged in activities – both academic and extra curricula – and for some students, a sense of belonging can be indicative of educational success and long-term health and wellbeing.

We know from PISA 2012 that, for Australian students, there was a very small positive relationship between sense of belonging and student performance and we will be looking at that again in the coming months.

We can also see that fewer students reported feeling supported by their teachers in mathematics lessons in 2022 than in 2012. The proportion of those who felt their teacher showed an interest in every student’s learning dropped from 73% to 68%, while the proportion of those who reported that their teacher gave extra help when students needed it, fell from 82% to 77%.

The disciplinary climate in Australian mathematics lessons was slightly worse than the OECD average, with 25% of students reporting they couldn’t work well in most or all lessons and 33% not listening to teachers.

Distraction from digital devices was significantly higher among Australian students than the OECD average indicates it was in other countries, with 40% distracted by using them (compared to 30%) and 37% distracted by others using them (compared to 25%).

We also learnt more about the impact of COVID-19 school closures from this data. During school closures, only 53% of students reported that they were supported daily through live virtual classes on a video communication system and 40% reported having problems at least once a week with understanding school assignments.

If schools had to close again in future, the same percentage of students in Australia as the OECD average (77%) felt confident or very confident about using a video communication system for learning.

However, the number who felt confident or very confident about motivating themselves to do schoolwork was much lower at 54% (and also lower than the OECD average of 58%).

What does the principal questionnaire show?

There’s been an increase in the proportion of principals reporting that the school’s capacity to provide instruction is hindered by teacher shortages (in Australia and about half of all countries with comparable data).

In 2022, 61% of Australian students were in schools affected by lack of teaching staff, compared to 17% in 2018, so that’s a really significant jump.

In most countries, students attending schools where the principals reported shortages scored lower in mathematics than students in schools whose principals reported fewer or no shortages.

We’ll dive further into the principal questionnaire data, and the teacher questionnaire data, in the May 2024 report.

References and related reading

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., & Thomson, S. (2023). PISA 2022. Reporting Australia’s results. Volume I: Student performance and equity in education. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-725-0.

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., & Thomson, S. (2023). PISA in Brief 2022: Student performance and equity in education. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-727-4.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I) The State of Learning and Equity in Education. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume II) Learning During – and From – Disruption. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/a97db61c-en.