Have you asked your students if they can see the writing on the board, in their own textbooks, or on devices clearly? Have you checked to see if they should be wearing glasses and do you encourage them to keep wearing them? In this article, optometrists Amanda Lea and Rebecca Dang share common eye-related behaviours to look out for in the classroom and practical teacher tips for encouraging good visual behaviours at school.

Teachers know better than anyone that children need to see well to learn in a classroom, because all typical classroom academic activities have some visual component (Narayanasamy et al., 2015). This article aims to succinctly summarise common questions teachers and parents have asked us as optometrists over the years and includes some handy infographics as easy reminders in the classroom.

When should I refer my student to an optometrist?

Modern classrooms have high visual demands, including a variety of distances and tasks. Optometrists can help with correction of what we call ‘significant refractive error’ (short-sightedness, long-sightedness and astigmatism) to ensure clear distance and near vision. We can also help with remediation of eye turns and convergence problems – an inability to point the eyes inwards so that both eyes are looking at a near target together – to ensure the objects children are viewing are singular and not doubling. We also assess for good ocular health. Spectacles may be recommended full-time or part-time (for example, only when doing near work or in the classroom), depending on the needs of the child. Sometimes, exercises are prescribed to help accurate ocular alignment.

Behaviours you might observe as a teacher

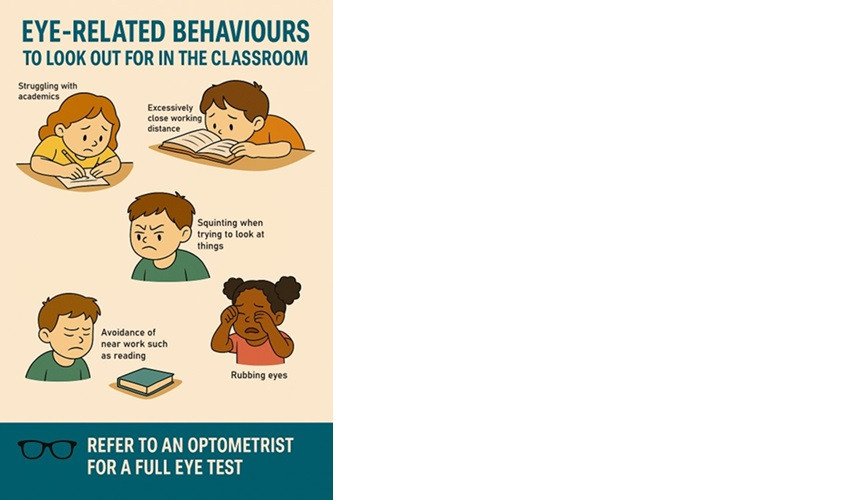

Teachers can look out for a number of behaviours that may indicate some sort of visual problem. Reading and screens are sometimes associated with reduced blink rates and dry eyes (Muntz et al., 2022), which manifests as burning, watering and stinging eyes. Children will often squint when they have blurry vision, which may indicate some refractive error. More subtle behaviours include struggling with schoolwork, holding reading material too close, or even avoidance of near work such as reading. We summarised these behaviours in the below infographic which you can download for printing here.

ADHD and learning

Children with ADHD are twice as likely as children without ADHD to need spectacles for long-sightedness, and 5 times as likely to have a convergence problem, which can cause eye strain and double vision (Bellato et al., 2023). As such, it is important to ensure these students have a full eye test to ensure learning activities are as impactful as possible.

The myth of eye tracking and reading

It has long been thought that lower reading skills are caused by poor eye tracking (that is, difficulties with accurately moving our eyes across the page as we read). However, recent literature demonstrates that poor eye tracking is a result, not a cause, of lower reading skills. For example, children with dyslexia have inaccurate eye movements when reading passages beyond their skill level, but these become accurate when the text matches their reading ability (Rayner, 1998) and children with ‘delayed’ and ‘non-delayed’ reading skills have similar eye movement patterns when the task is a non-reading, picture-based, one (Vinuela-Navarro et al., 2017). Tracking improves as reading becomes more automatic.

The myth of visual processing and learning

Implementing targeted vision interventions (also known as ‘vision therapy’) to support students with processing visual information is not strongly supported by the evidence to improve their academic outcomes. Indeed, a recently published randomised controlled trial demonstrated that therapy for visual processing did not improve academic skills, compared to a placebo therapy, for early primary school children in the bottom third of their class for literacy (Fricke et al., 2023). Note that vision therapy is different to exercises for eye misalignment (or 'convergence') problems, which are evidence-based.

Children who are struggling learners or who have attention problems should have an eye exam, but it need not address ‘visual processing’ or ‘eye tracking’ as these are not contributors to reading ability. Therapy for visual processing to improve academic ability is not evidence-based.

What can I do to protect my students’ vision?

Making vision easier

Classroom materials should feature high contrast and age-appropriate fonts to support readability. With the growing use of digital devices and smart boards, glare has become a common visual obstacle, especially when screens reflect light from windows or overhead fixtures, potentially obstructing students' view. Additionally, colour vision deficiency affects approximately 8% of boys and 0.5% of girls, often causing confusion between certain colours. To accommodate this, learning materials should be designed with accessibility in mind. Key strategies include maintaining strong contrast between text and background; and avoiding the use of colour alone to convey meaning, supplementing with labels, patterns, or shapes. Fortunately, there are now simple apps available that simulate colour vision deficiencies, allowing educators to test and refine their materials for inclusivity.

UV protection

Eighty percent of Australian teenagers have detectable ultraviolet light eye damage (Ooi et al., 2006) which is associated with the development of eyelid malignancies, ocular surface diseases, and cataracts (Yam & Kwok, 2014). The Australian sunglasses standards are robust, and there are many good quality options for children. Parents and students should be looking for sunglasses that meet the Australian standard for level 1 or 2 lenses, which provide medium to high glare protection and good UV protection.

Support and encourage UV protection with sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats outdoors. The protective effects on myopia (explained below) are still present with good sun protection!

Myopia prevention and control

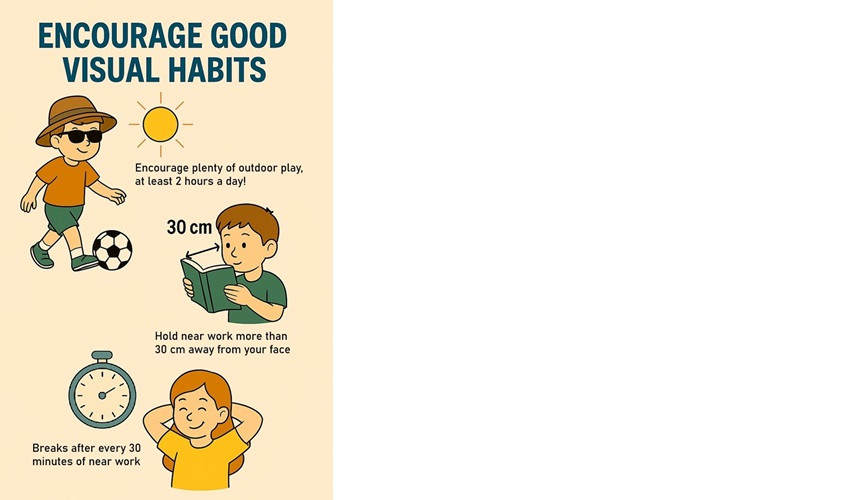

Another important childhood eye condition that teachers can help protect their students from is myopia – which is caused by excessive eye growth during childhood and causes an inability to see far away without spectacles. It is increasing in prevalence, and a public health concern because of the long-term increased risk of eye disease (Holden, et al., 2016). Teachers can help encourage good habits which can help reduce the onset of myopia – this includes making sure children are holding reading material more than 30cm away from their eyes, are taking regular rest breaks from near work at least every 30 minutes (Jonas et al., 2021) and encouraging at least 2 hours outdoors every day (Rose et al., 2008). A handy tip is to take reading or homework outside, as the protective benefits of being outdoors are still present even while reading!

Recommend your students to see an optometrist if you notice them squinting at the board. Regular routine eye tests can help early identification of myopia, and access different treatments (spectacles, contact lenses or eye drops) that help prevent myopia progression (Wildsoet et al., 2019).

We’ve created an infographic, Encourage good visual habits, for you to print and display. Click here to open the infographic in a new tab and download it.

References

Bellato, A., Perna, J., Ganapathy, P. S., Solmi, M., Zampieri, A., Cortese, S. & Faraone, S. V. (2022). Association between ADHD and vision problems. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry. 28, 410-422. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-022-01699-0

Ehri, L.C. (2020). The Science of Learning to Read Words: A Case for Systematic Phonics Instruction. Reading Research Quarterly. 55, S45-S60. https://ila.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/rrq.334

Fricke, T. R., Metha, A. B., Anderson, D. P., Lea, A. K. & Anderson, A. J. (2023). Does vision therapy for visual information processing improve academic performance? A randomised clinical trial. Ophthalmic and physiological optics. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/opo.13222

Grajo, L. C., Candler, C. & Sarafian, A. (2020). Interventions within the scope of occupational therapy to improve children’s academic participation: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 74(2). https://research.aota.org/ajot/article/74/2/7402180030p1/6676/Interventions-Within-the-Scope-of-Occupational

Holden, B. A., Fricke, T. R., Wilson, D. A., Jong, M., Naidoo, K. S., Sankaridurg, P., Wong, T. Y., Naduvilath, T. J., Resnikoff, S. (2016). Ophthalmology. 123(5), 1036-1042. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0161642016000257?via%3Dihub

Jonas, J. B., Ang, M., Cho, P., Guggenheim, J. A., He, M. G., Jong, M., Logan, N. S., Liu, M. Morgan, I., Ohno-Matsui, K., Parssinen, O., Resnikoff, S., Sankaridurg, P., Saw, S., Smith, E. L., Tan, D. T. H., Walline, J. J., WIldsoet, C. F, Wu, P. … Wolffsohn, J. S. (2021). IMI prevention of myopia and its progression. Investigative ophthalmology and visual science. 62(6). https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2772536

Muntz, A., Turnbull, P. R., Kim, A. D., Gokul, A., Wong, D., Tsay, T. S., Zhao, K., Zhang, S., Kingsnorth, A., Wolffsohn, J. S. & Craig, J. P. (2021). Extended screen time and dry eye in youth. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. 45(5). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1367048421001764

Narayanasamy, S., Vincent, S.J., Sampson, G. P. & Wood, J. M. (2015). Impact of simulated hyperopia on academic-related performance in children. Optum Vis Sci. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25525890/

Ooi, J. E., Sharma, N. S., Papalkar, D., Sharma, S., Oakey, M., Dawes, P. & Coroneo, M. T. (2006). American Journal of Ophthalmology. 141(2), 294-298. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002939405010147?via%3Dihub

Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 372-422. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.124.3.372

Rose, K. A., Morgan. I. G., Ip, J., Kifley, A., Huynh, S., Smith, W. & Mitchell, P. (2008). Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 115(8), 1279-1285. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0161642007013644?via%3Dihub

Vinuela-Navarro, V., Erichsen, J. T., Willians, C. & Woodhouse, J. M. (2017). Saccades and fixations in children with delayed reading skills. Ophthalmic and physiological optics. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/opo.12392

Wildsoet, C. F., Chia, A., Guggenheim, J. A., Polling, J. R., Read, S., Sankaridurg, P., Saw, S., Trier, K., Walline, J. J., Wu, P. & Wolffsohn, J. S. (2019). IMI – interventions for controlling myopia onset and progression report. Investigative ophthalmology and visual science. 60, M106-M131. https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2727315

Yam, J. C. S. & Kwok, A. K. H. (2014). Ultraviolet light and ocular diseases. International Ophthalmology. 34, 383-400. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10792-013-9791-x

How do you ensure your classroom materials are accessible to students with colour vision deficiency? Have you considered the use of colour and font choice?

Is glare an issue in your classroom? What adjustments could you make to reduce glare and improve visibility when students are using digital devices?