Deakin University’s Economics + Maths = Financial Capability project set out to research what can be done differently to support secondary school teachers to prepare financially capable young people. As part of this project, Dr Carly Sawatzki, Dr Jill Brown and their colleagues have compiled insights from educational research undertaken in Australia and overseas; surveyed and interviewed education professionals, secondary school teachers and students; and designed and tested a course to develop teachers’ interdisciplinary knowledge of finance-related curriculum, concepts and contexts.

In today’s article, Dr Sawatzki and Dr Brown discuss what they learned from young people and professional educators that may be informative to policy and decision makers, school leaders and teachers, and what they want to see happen next.

Are young people getting the financial education they need and deserve? Put simply, no.

While the Australian Curriculum frames opportunities for students to learn about finance, curriculum enactment varies across states and territories and from school to school. Some secondary schools address finance-related curriculum within Economics and Maths, while others offer interdisciplinary or thematic programs, often as elective studies.

Research in Australia and overseas repeatedly shows that teachers believe that financial education is important, but do not feel well-prepared or confident in the role of ‘financial educator’.

While Australian students generally perform well on the OECD PISA financial literacy assessment, there has been little improvement over the past decade. Australia has a high proportion of students achieving below Level 2, which is the baseline level of proficiency. Low performers struggle to apply their knowledge to real financial problems and decisions.

Further, the financial landscape is dynamically changing, while financial education at school is lagging behind. Unfortunately, current approaches are short-changing young people, leaving too many inadequately prepared for an increasingly complex and digitised financial world.

Hold on, isn’t this parents’ responsibility?

The OECD PISA financial literacy assessment includes questions about students’ opportunities to acquire money-related knowledge at home and through personal experience. Many Australian young people report developing financial knowledge outside their school, mostly from their parents, other adult family members, and the internet. This is called financial socialisation.

While family, community, and social networks are powerfully influential in shaping what young people come to know about money, access to factual and trustworthy information varies.

There are new forms of financial risk and deception, and a growing number of social media ‘finfluencers’ on platforms like TikTok and Instagram. We know that ‘get rich quick’ stories can be seductive. These are just some of the reasons why financial education at school is more important than ever.

What did the young people in our study teach us?

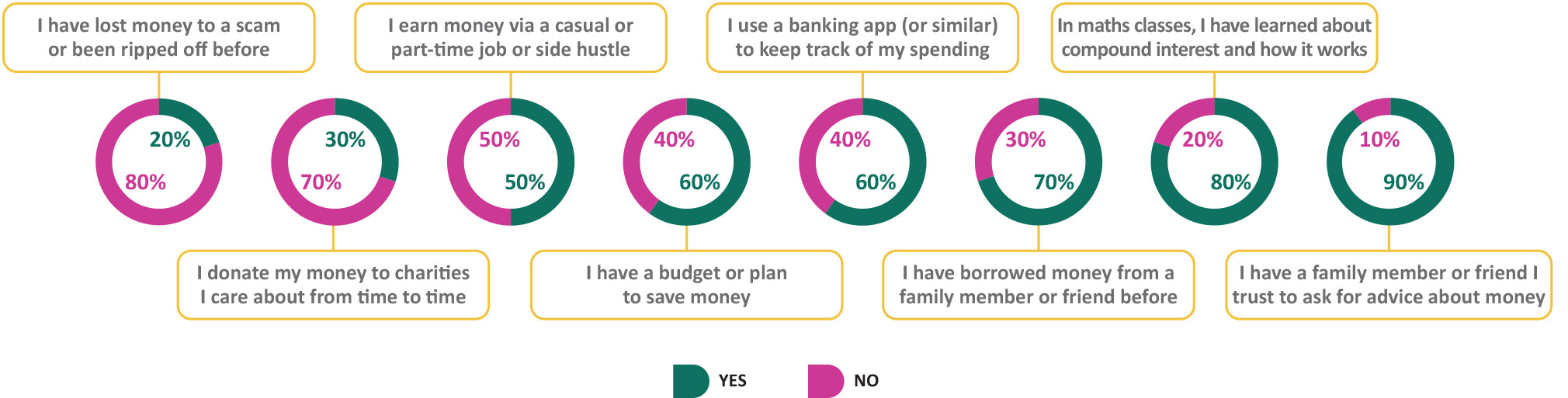

Our virtual student summit involved more than 120 young people aged 15 to 16 years and from a range of backgrounds. Most were already financially active. Half were earning money via a casual or part-time job or ‘side hustle’. In fact, we met students working more than one job, as well as young entrepreneurs operating websites. Three in 5 were using a banking app (or similar) to keep track of their spending and had a budget or plan to save money. One in 5 reported having lost money to a scam or being ripped off before. Many had borrowed money from a family member or friend.

Importantly, the vast majority reported having a family member or friend that they trust to ask for advice about money. When asked, ‘What is the best advice about money you’ve ever been given?’ students indicated that their families and communities were encouraging them to live within their means, spend wisely, save, and invest. In fact, some were already siphoning a proportion of their money into a separate bank account, or investing in shares and crypto.

Of course, financial life is an uneven playing field, and not all students have the family support and resources that make these activities possible. In fact, one in 5 students reported that they did not have access to conversations about money matters at home at all. However, most students agreed that their parents/caregivers want them to learn about money matters at school.

Most students agreed that learning Economics and Maths can help them make informed financial choices. However, less than half could see clear connections between their learning across these disciplines. One in 5 could not see these connections at all. This is a key insight that tells us where we need to do a better job.

We asked students what they wanted to learn across Economics and Maths. They told us that they want programs and lessons that are connected to the real world and useful to their future. They want to be shown how to do everyday things, like keep track of money and keep good financial records, and read and check the calculations on payslips (including tax and super), invoices, and bills.

It is interesting to note that students assigned less importance to learning how to access government support like Centrelink, Medicare, and the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Colleagues’ research exploring 18- to 24-year-olds’ financial perspectives and strategies would seem to indicate this reflects a fear of stigma and judgment talking about financial struggles. We argue that as voters and taxpayers, students deserve to learn that the taxation system is a collective asset, and government support and payments form part of the social contract of a democracy.

While students varied in their financial experiences and learning interests, the takeaway from our study is that rich knowledge and practical insights exist within this age group. These are the strengths and foundations upon which financial education at school must build.

What we learned from professional educators

The professional educators in our study identified a lack of genuine support for school leaders and teachers to assume local ownership and get creative in how they enact the finance-related curriculum. The teachers we interviewed spoke of the need for help tailoring their programs and lessons to students’ family, cultural, and community backgrounds, as well as their ever-changing learning needs and interests.

These comments convey the sentiments of many we spoke to:

‘If you’re not trained adequately, it’s just a blind spot…’

‘We’re only ever going to improve education in Australia if we improve the quality of teaching. And that means teaching teachers. So, it’s about teacher education, teacher professional learning.’

The teachers who completed our course reported that doing so enhanced their knowledge of students’ finance-related learning needs and interests and strengthened their classroom teaching. Those who received system- and/or school-level support to learn and innovate were able to strengthen their schools’ existing programs and/or develop new offerings. These results were achieved in a relatively short period of time (i.e., 6 x 90-minute sessions over a 12-week period).

What we want to see happen next

The new Australian Curriculum v9.0 frames opportunities to teach and learn about finance, particularly in Economics and Maths, but also via a focus on the General Capabilities, including digital literacy. There is the potential for this curriculum reform to mark the start of a new era in financial education.

Our report makes two recommendations to Commonwealth Treasury, together with Australian, State and Territory education Ministers, and we have identified associated actions that Australian, State and Territory education and curriculum authorities can take to get things moving in the right direction.

Our previous articles for Teacher explain the sorts of things that can be done at the school level to strengthen programs and connect with students’ experiences with fintech developments. We’ve also discussed how students’ interest in crypto can be used to teach about financial risk, reward, and regulation.

To read the full report, Economics + Maths = Financial Capability Research Report, click on the link.

The Economics + Maths = Financial Capability project was proudly supported by Ecstra, a charitable foundation committed to building the financial wellbeing of Australians within a fair financial system.

References

Cordoba, B. G., Walsh, L., Waite, C., Cutler, B., & Mikola, M. (2022). Young people's financial strategies: insights from the Australian Youth Barometer. https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/report/Young_people_s_financial_strategies_Insights_from_the_Australian_Youth_Barometer/21266553

Sawatzki, C., Brown, J., Powers., T., Prins, R., & Zmood, S. (2022). Economics + Maths = Financial Capability Research Report. https://doi.org/10.26187/702w-...

Thomson, S., De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., & Schmid, M. (2020). PISA 2018: Financial Literacy in Australia. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://research.acer.edu.au/ozpisa/48

The financial landscape is dynamically changing. As an educator, how do you stay abreast of changes in the finance sector? Are there any particular resources you use to access this information?

The professional educators in this study identified a lack of genuine support to get creative in how they enact the finance-related curriculum. Do you approach financial education in a creative way? Are there any opportunities to be innovative in the way you deliver these lessons to students?