In any given lesson, when do teachers shift from being ‘information providers' to becoming facilitators of learning with their students? Do teachers know when to interrupt student thinking and provide the appropriate scaffolds? And, how can educators transition students from being teacher reliant, to independent and interdependent learners in the classroom?

These questions highlight the critical elements of instructional scaffolding in the classroom. In this article, we uncover the answers to these questions and explore, through an instructional scaffolding model, the importance of developing students' responsibility for their learning. We also provide a practical framework for cultivating student independency and interdependency in the learning process.

Understanding the theory

Instructional scaffolding as a strategy for supporting learners begins with Lev Vygotsky's sociocultural theory and his learning concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). Specifically, his sociocultural theory asserts that cognition is developed through social interaction.

Vygotsky coined a definition of instructional scaffolding that focused on teacher practices. He defined this as, ‘the role of teachers and others in supporting the learner's development and providing support structures to get to that next stage or level' (Raymond, 2000). Vygotsky believed that learning does not occur in isolation. Rather, learning is a social process, guided by interactions with classmates and others involved in the lesson.

A second layer to instructional scaffolding exists with Vygotsky's conceptual thoughts about supporting independency. This support mechanism – ZPD – is the difference between what a learner can do independently and what a learner can complete with adult support or scaffolding practices.

Vygotsky committed to his belief that instructional scaffolding and application of these scaffolds at the ZPD allowed for any child to successfully learn in any area. The activation process of the ZPD is initiated when content is taught just outside of the student's current skill and knowledge level. This ignites a student's motivation to know more about the content and, as a result, pushes forward the learner's effort to work beyond their current skill level.

Enabling students to become problem solvers

As students transition from receiving direct instruction from the teacher, towards independent problem solving and networking with other classmates, the need for instructional scaffolding is essential if students are to acquire skills that will help them lead their own learning.

This work requires individuals to develop into highly interactive, solution-oriented, and effective communicators and contributors, resulting in effective process thinking. This means current classrooms should make available ample opportunities to practice these skills so that students are fully equipped with leadership capabilities that align with workplace requirements for interdependency.

An ‘I Do, We Do, You Do' framework

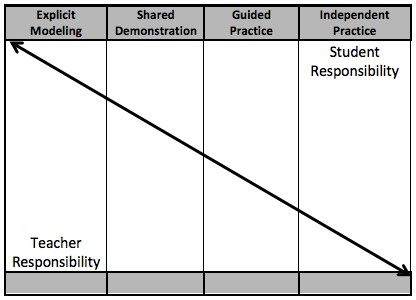

Instructional scaffolding supports student learning and growth by shifting cognitive engagement from the teacher to the student (Fisher & Frey, 2007). As the educator delivers new content to the student, they must be aware of each student's location within the ZPD

The ZPD identifies the level of independency in the learner – more specifically, it identifies gaps in learning and skills. Understanding a student's location within the ZPD supports self-efficacy as a result of the gradual release framework ‘I Do, We Do, You Do.'

The gradual release framework originates with teachers demonstrating and modeling the learning for their own students – referred to as ‘I do'. Here, the teacher is implementing approximately 90 per cent of the ‘heavy lifting' or work (Archer & Hughes, 2011). During this phase of the instructional process, most actions (explicit instruction) are presented by the teacher.

Within this direct instruction time, it is important that students show their engagement with an overt behaviour as the teacher scaffolds and checks for understanding. This overt behaviour makes up approximately 10 per cent of the student responsibility in this first phase of teaching and learning.

These student actions or responses could include: signaling, pairing and sharing with a peer, writing a response, showing a written response via a whiteboard, or actively participating in a cooperative learning activity. The emphasis here is that an observable student action is mandatory so that teachers can see the level of understanding from each individual student at this early stage of learning new content.

As teachers and students transition from the first to the second phase of the release framework, or ‘We do', the level of responsibility begins to shift as well for both student and teacher. Within this next stage, the heavy lifting is almost equal as the teacher begins to transition more learning ownership on to the students. Specifically, students own 40 per cent of the learning responsibility within this guided practice portion of the gradual release of responsibility model. At this point, the teacher being still highly involved, works side-by-side small groups of students.

The teacher might structure a small group question for students to answer, create an application activity that aligns with the learning, or provide word webs, concepts maps, and graphic organisers for students to organise learned content. The role of the teacher balances leading instruction with a more facilitative and indirect formative assessment of the new learning. The teacher frequently moves throughout the classroom observing and checking in on individuals and small groups as students demonstrate their learning.

Once the teacher determines readiness on the part of her or his students, the learners take on the last stage of the framework – an independent practice approach described as ‘You do'. Approximately 90 per cent of the responsibility is placed on the students for their own learning and mastery of the content.

At this phase, the students are comfortable with the content and can easily progress through learning activities assigned, participate in small and large group discussions with little assistance by the teacher, can generate new questions and discussions, and apply the newly learned content. Teachers fully facilitate the learning, listen in on conversations, and formatively assess the progress of each student.

Productive struggle provides an opportunity for students to think through and grapple with complex concepts that may have multiple reasonable outcomes. The ability to facilitate student conversation is a skill that master teachers often demonstrate.

Skillful educators encourage students to agree, disagree, debate, and contribute alternative answers to a central content being discussed. As a result, teachers allow student teams to persist with the concept, in which complex thinking and heavy lifting resides with the students.

Figure 1. Share of responsibility for task completion in the ‘I Do, We Do, You Do' framework, adapted from Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. (1983).

An independent and interdependent learner

The gradual release framework facilitates the creation of independent learners through personalised learning and academic goal setting. In this process, these students realise the importance of rigorous personal goals and make connections to real life experiences.

Students as independent learners should exhibit the following qualities:

- Establish a personal learning goal

- Initiate action plans to achieve learning outcomes

- Lead conversations connected to a lesson or unit of inquiry

- Make connections to content and community

- Monitor personal academic goals

- Respond to feedback as a frame for individual continuous improvement

Students as interdependent learners should exhibit the following qualities:

- Collaboratively set a group learning goal

- Expand on others' thoughts

- Help classmates understand content and make community connections

- Initiate action plans to achieve group learning outcomes

- Monitor group academic goals

- Respond to feedback as a frame for group continuous improvement

Teachers support independent and interdependent students by facilitating the learning process rather than directing it. Creating an environment that fosters goal setting and collaboration in the ZPD promotes students to develop from teacher-reliant into self-sufficient learners (Vygotsky, 1978).

As a result of this, students experience greater self-efficacy through ownership of their learning experiences by advocating for themselves and leading peer collaborations.

References

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. Guilford Press.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2007). The formative assessment action plan. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. C. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 317-344.

Raymond, E. (2000). Cognitive Characteristics. Learners with Mild Disabilities (pp. 169-201). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon, A Pearson Education Company

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

As a classroom teacher, how do you ensure that you’re teaching content just outside of the students’ current skill and knowledge level? Do you find that this motivates students to want to know more about the content and pushes them to work beyond their current skill level?

The authors of this article say that teachers support independent and interdependent students by facilitating the learning process rather than directing it. How do you go about facilitating your lessons? Have you found that this approach encourages students to be less reliant on you as the teacher?