During the pandemic, many learning resources became available online. The number of resources available now can be overwhelming, and it might involve a bit of trial and error to see what best suits the learning needs of your students.

Early-career teacher at Tasmanian eSchool, Ruby Lyons-Reid, has recently been recognised for her use of digital resources to engage students in learning about First Nations histories and cultures, by being named recipient of the Public Education Foundation’s Teachers Health Early Career Scholarship, a $10 000 scholarship for professional development awarded to a teacher in their first three years of their career.

At Tasmanian eSchool, the state’s online distance education provider, Ruby Lyons-Reid is the Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) Learning Area Leader and Aboriginal Curriculum Leader. She also teaches Year 11 and 12 English, Creative Writing and Tasmanian Aboriginal Studies.

The K-12 school currently has almost 500 students enrolled. A majority of the students are based in Tasmania, but some are enrolled from interstate or overseas, and a high percentage are Indigenous Australians. She will be utilising her funding to undertake professional learning on the topic of First Nations curriculum leadership and culturally responsive planning.

Using digital resources to learn about First Nations histories and cultures

During her few years teaching at the Tasmanian eSchool, Lyons-Reid says she has found effective ways to engage students in learning about Indigenous Australians through some trial and error.

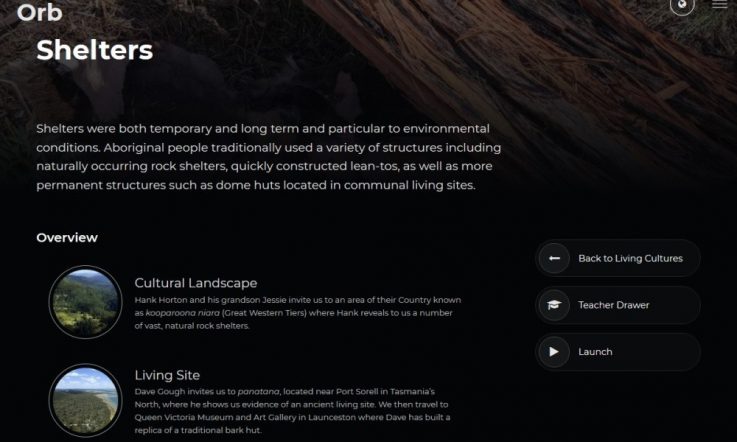

‘Some strategies and tools have worked really well, others less so. The most valuable resource I use is The Orb website, developed by Aboriginal Education Services, Department of Education, Tasmania,’ she tells Teacher.

‘I embed sections of The Orb in Canvas (the Learning Management System we use at the eSchool), and while this doesn’t replace the experience of going out on Country and learning from sharers of knowledge in-person, it does allow me to centre Aboriginal voices in a really engaging way. I’ve found that students much prefer learning through these vibrant multimodal resources rather than reading dry text.’

Lyons-Reid has also found success with the use of lightboards and interactive maps, like Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s place name map for her Tasmanian Aboriginal Studies class. She’s also used Flip, a discussion and video sharing app, to record and share Acknowledgements of Country.

For NAIDOC Week last year, Lyons-Reid supported a group of students to create a representation of their local Country in Minecraft to be entered into the Indigital Minecraft Challenge where they were named finalists. ‘The students used coding skills to build a wall with petroglyphs, an ochre mine, shells in the river to be collected for stringing, and a cultural centre with a guide who shared knowledge about invasion and contemporary language revival.’

She has also had success facilitating a virtual excursion for her students, to ensure they had the opportunity to enrich their Aboriginal studies learning. To facilitate the excursion, Lyons-Reid worked closely with staff at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

‘We trialled a few different technologies and approaches before the excursion. In the end, I used an iPad on a tripod to film the excursion live in the museum and students joined through our virtual BlackBoard Collaborate classroom. This allowed students to ask questions in real time, view cultural objects up close, learn from a knowledgeable First Nations guide, and to engage with concepts and content in a more real and engaging way,’ she shares.

Embedding Indigenous perspectives in English lessons

Lyons-Reid has also utilised a virtual excursion to the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra to support students’ learning in her Year 11 and 12 English Writing class.

‘I designed a short topic in my English Writing class about ekphrastic poetry, which is writing about visual art. Students learn about the form, read examples and then have a go at writing their own.’

The excursion facilitated engagement with artworks of and by First Nations people. ‘I think ekphrastic writing is a fantastic tool to learn about First Nations histories and cultures in the English classroom, because it allows students to practice writing techniques to describe art objects through language, but also to weave in ideas about the artist’s context, and the people, history and culture represented in the works,’ she explains.

Culturally responsive planning and teaching

In an online context, it’s still important to create culturally safe learning spaces.

Lyons-Reid’s scholarship will also involve professional development on the topic of culturally responsive planning. She hopes it will help her develop an understanding of how to create these spaces, and ‘how best to design engaging and culturally responsive First Nations teaching and learning programs for digital classrooms.’

Being culturally responsive as a teacher, she shares, involves taking the time to reflect on your own cultural identity and worldview.

‘It is important to recognise how your own biases and stereotypes might lead you to make assumptions about the learners in your classroom,’ Lyons-Reid tells Teacher. ‘For example, what they know, why they behave in certain ways, and what they can achieve. I think it is about being sensitive and reflective; having high expectations for all students; and being open to learning from students as much as they are learning from you.’

In what ways have you utilised digital resources in your classroom so far this year? Have you facilitated engagement in external resources, like online competitions?

Are there any resources mentioned by Ruby Lyons-Reid in this article that you think may enhance student learning in your context? Is there room to try these out next term?