The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) measures the knowledge and skills of 15-year-old students in mathematics, science and reading, and how well they are prepared to use these to meet real-life opportunities and challenges.

Over the last few months, Teacher has been delving into the latest PISA data to find out how Australian students are faring, and explore how education systems around the world are working to lift student outcomes. So far, we’ve shared details of Singapore’s home-based learning initiative, equity lessons for the AI era, 'resilient’ education systems (Japan and Lithuania), the digital learning ‘sweet spot’ and what the data show about Australia’s PISA performance and student experiences. The topic for today’s article is classroom disciplinary climate and, in particular, digital distractions.

Every few years, tens of thousands of students sit the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Alongside the academic testing, each PISA cycle includes a questionnaire to gauge the thoughts, feelings and experiences of principals and students on a range of topics.

In PISA 2022, one of the topics explored in the questionnaire was disciplinary climate.

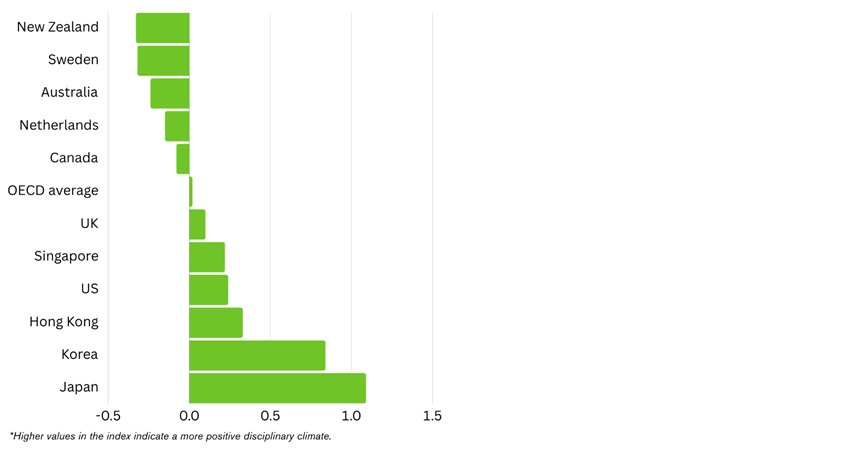

Students were asked to respond to a range of statements on disciplinary issues with how often they occurred in their class. Because the main measurement domain for PISA 2022 was mathematics, all the statements related to mathematics classes specifically. These responses were then combined to create an index of disciplinary climate.

According to analysis of Australia’s PISA results by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), ‘Australian students’ reporting of disciplinary climate was one of the least favourable among the comparison countries that performed higher or the same as Australia in mathematics in PISA 2022 … All but 2 [of these comparison] countries (Sweden and New Zealand) had a more favourable disciplinary climate than Australia,’ (De Bortoli et al., 2024).

While a range of disciplinary issues contribute to Australia’s unfavourable disciplinary climate, one driving factor is digital distractions.

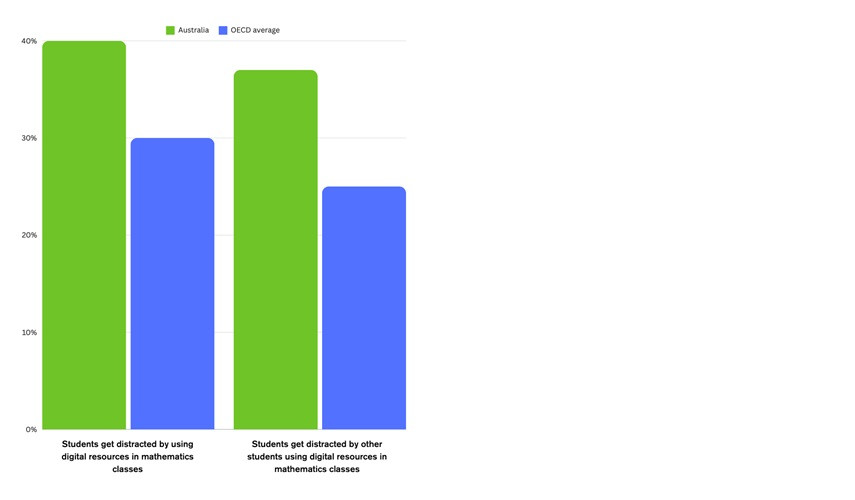

In PISA 2022, students were asked to respond to the following statements on digital distractions, with how often they occurred (every class, most classes, some classes, never or hardly ever) in their mathematics lessons:

- Students get distracted by using digital resources (e.g. smartphones, websites, apps).

- Students get distracted by other students who are using digital resources (e.g. smartphones, websites, apps)

As shown in the graph below, a higher proportion of Australian students reported becoming distracted by digital resources in ‘every’ or ‘most’ classes, than on average across the OECD.

The ACER report also analyses Australian students’ responses by jurisdiction and across a range of demographics groups. Findings include:

- Fewer students in Victoria and New South Wales than in South Australia reported that students get distracted by other students who are using digital resources in most classes.

- A smaller proportion of female students than male students reported that students get distracted by other students who are using digital resources (36% compared to 38%).

- A greater proportion of students from disadvantaged than advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds reported that students get distracted by using digital resources (43% compared to 38%), and that students get distracted by other students who are using digital resources (38% compared to 34%).

- A greater proportion of First Nations students reported that students get distracted by using digital resources 47% (compared to 40%), and that students get distracted by other students who are using digital resources (45% compared to 37%).

(De Bortoli et al., 2024)

Digital distractions in the classroom are a cause for concern, as this can impact student learning and wellbeing.

According to the OECD (2023) international PISA 2022 report, ‘on average across OECD countries, students who reported that they become distracted in every or most mathematics lessons scored 15 points lower in mathematics than students who reported that this never or almost never happens …’.

To put that into context, ‘20 points represents the average annual pace of learning of 15-year-olds in countries that participate in PISA’ (OECD, 2023), meaning that a 15 point gap equates to around three-quarters of a year of learning.

In addition to the academic impact of distraction, the OECD (2023) adds ‘finding effective ways to limit distractions is also important for student well-being. For example, in all countries/economies students who perceived the climate in their mathematics lessons to be less disruptive were less anxious towards mathematics.’

Digital resources in the classroom – policies and use

Australian schools are increasingly using a range of digital devices and resources to support teaching and learning – Australia was one of just 7 countries in PISA 2022 where ‘the computer-to-student ratio was higher than one-to-one,’ (OECD, 2023).

However, while digital resources can be a benefit to teaching and learning, ‘students who use digital devices in mathematics class more frequently reported that they are likely to become distracted …’ (OECD, 2023).

The OECD says, to minimise the risk of distraction, teachers should consider how students are using digital resources in the classroom, and the types of digital devices that they rely on.

How students use digital resources

The PISA 2022 international report highlights the importance of schools having clear, enforceable policies, practices and guidelines on the use of digital resources.

‘The content and design of such rules, as well as the capacity to enforce them, likely play a critical role in determining their effectiveness. When a school’s written statements or rules are too generally designed, imprecise or lenient, they are unlikely to support effective teaching and learning with digital devices. Schools and teachers also need the time and capacity to enforce such rules,’ (OECD, 2023).

It also notes that in PISA 2022, and consistent with PISA 2018 data, ‘student-led uses of digital devices in class were negatively associated with student performance in reading, science and mathematics, whereas teacher-led or combined student-teacher uses of digital technologies tend to be more effective,’ (OECD, 2023).

Types of digital devices

While effective policy around the use of digital resources is crucial in limiting distractions, certain devices and resources – namely smartphones – have a higher associated risk than others.

‘… students who used smartphones at school more frequently reported that they were likely to become distracted while using digital devices in mathematics lessons … By contrast, the use of educational software at school has a more moderately negative association with students’ concentration, suggesting that the use of digital resources with pedagogical intent makes a difference, although it does not completely eliminate distractions,’ (OECD, 2023).

The role of phone bans

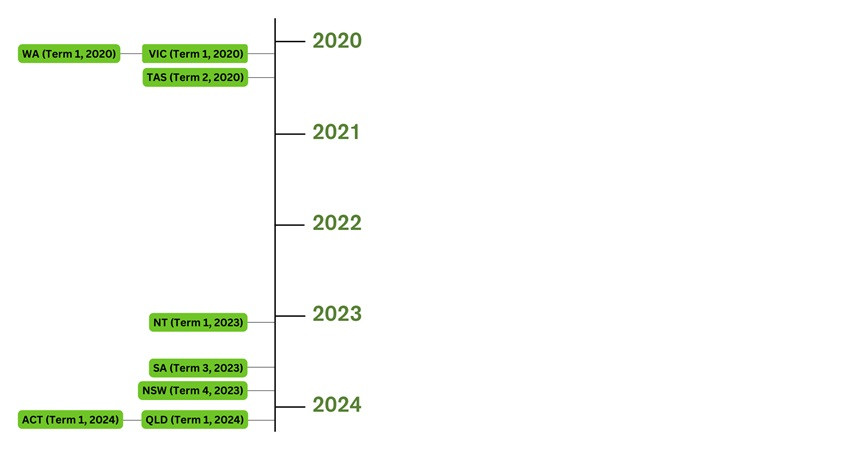

When looking at Australia’s latest PISA results, it is important to note that when students completed the questionnaire in 2022, the majority of states and territories had not yet passed legislation restricting the use of phones in school. And, a reminder that state and territory-level phone policies are only applicable to public schools, with private schools in charge of setting their own policies.

Note: Specific rules around how phone use is restricted may vary by state/territory and year group. For example, year 11 and 12 students in ACT public schools are only required to put phones away during class hours, with no restrictions on out-of-class use, such as during lunch and recess. NSW has enforced a mobile phone ban in public primary schools since 2019, with the later 2023 restrictions applying to public secondary schools.

While phone bans may help limit distractions, policies need to be effectively enforced – something the PISA 2022 international data suggests is not always the case.

‘On average across OECD countries, 29% of students in schools where the use of cell phones is banned reported using a smartphone several times a day, and an additional 21% reported using one every day or almost every day at school,’ (OECD, 2023).

References

OECD (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Learning During – and From – Disruption. PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/a97db61c-en.

De Bortoli, L., Underwood, C., Friedman, T., & Gebhardt, E. (2024). PISA 2022. Reporting Australia’s results. Volume II: Student and school characteristics. Australian Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.37517/978-1-74286-726-7

According to PISA 2022 data, students get distracted even when using digital resources for learning purposes. How do you provide opportunities for students to learn digitally, while ensuring they stay focused and on task?

As noted in the OECD’s international report, ‘… teacher-led or combined student-teacher uses of digital technologies tend to be more effective.’ Does your approach to digital learning align with this?

Across participating countries and economies, around half of all students attending schools with phone bans reported still using their phones regularly. How often does your school review its phone policies? How do you measure their effectiveness?