Biophilic design in schools is now a necessity. This may not seem like such an extreme statement when it is viewed within the context of both the current COVID-19 pandemic and the climate change crisis. Our urban lives are seemingly so removed from and out of touch with the natural world, and yet humanity is a part of nature and, whether we like it or not, we are part of its systems.

Schools have an important role in teaching children that our relationship with our natural context can be symbiotic. This role is made much easier by the numerous joys and educational benefits afforded by biophilic design.

Sustainable and biophillic design are not the same thing but they are particularly compatible. Sustainable design is about designing to support natural systems (ie: to not waste energy or resources) for the sake of the environment. Biophilic design is about integrating urban settings with nature for the sake of the occupant's health and mental wellbeing.

Learning from early childhood settings

In early childhood settings the importance of the outdoor play area is supported legally by the national code requirement of 7m2 unencumbered area per child. But in schools it is possible for demountable classrooms to be scattered across the playground whenever the school population increases, with no regard for the critical role outdoor play areas or access to the great outdoors plays in our cognitive development and wellbeing. The increasing demand for school placements in the competitive real estate market means that more will need to be multi-storey or ‘vertical' and thus access to outdoor areas may be even more allusive.

Primary and high school design can learn from the outdoor-focused design prerogatives of early learning settings. Designs that have a focus on strong indoor/outdoor connections and that foster children's sensory interaction with their context. In my experience, educators in Australia are asking for better connections between indoor and outdoor spaces and greater access to natural environments.

Benefits of biophilic design

The benefits of biophillic design have been extensively researched. Future Proofing Schools; Phase 1 Research Compilation is an Australian Research Council Linkage Project led by the University of Melbourne. It provides precise data on the positive impacts of natural ventilation, natural lighting, good acoustics and indoor air quality on both the staff and children. Providing spaces that are open and connected to the outdoors increases mental stimuli, energy and physical comfort levels and this, in turn, increases cognitive ability, attention and memory levels (O'Brien & Murray, 2007).

However, biophilic design is not just about these basic health and performance requirements. It is also about the innate human need to connect with other living things, with nature. Within a school context, connection with nature provides mental relief and feelings of wellbeing. The Living Future Institute, an international biophilic design organization, provides guides on how to create a biophilic environment and its website features case studies from around the world – including this school science wing.

As a quick summary, a biophilic interior is created by:

- maximising natural light and ventilation;

- having openable windows with views of the sky and trees that also allow the external natural soundscape to be heard;

- using natural materials and textures in the internal and external fitout for increased sensory experience; and,

- providing access to landscaped settings, as both retreat spaces and communal areas, which (however small) incorporate a whole ecosystem – including fauna, flora, rocks and water within them.

If your school is in an urban context, these natural and landscaped settings can be effectively recreated internally by:

- using programmed temperature changing LED and full spectrum lighting;

- minimising mechanical air conditioning in favour of natural ventilation or using systems with a high fresh air component;

- having controlled framed views of the external natural features available; and,

- building internal landscapes that are integrated within the built form and that can support biodiversity.

These same systems can be used to create sustainable design features such as filtrating water on site for reuse and minimising the energy used to support artificial air and light.

Natural systems pedagogy

Across the world outdoor schooling has been gaining popularity as one way to provide children and teenagers with greater access to nature (Scott, 2010, p.16). Here in Australia, at a high school level, outdoor school programs such as Timbertop at Geelong Grammar School in Melbourne and Glengarry at The Scots College in Sydney provide students with an immersive experience where they get to experience both the wonders and the challenges of nature, learning how to deal with risk and building and analysing their own relationship with the landscape.

But natural engagement also needs to be functionally integrated within a schools' daily program to be truly effective. Incorporating exposure to nature within the school program allows the students to learn about natural systems over time, perceiving the changes and evolutions of life in microcosm and in relation to themselves. Involving the students in observations and maintenance of the gardens, the ecosystems and the buildings' sustainability systems and incorporating these observations within their studies allows for a more immersive experience and for better educational outcomes (Franco et al., 2017).

Design examples

An early childhood example of natural engagement within an urban setting is the ToBeMe childcare centre in Drummoyne, Sydney by Scott and Ryland Architects.

ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects. Green rooftop in a light industrial setting, bringing nature to where it is most needed.

The 160 child centre is built within a repurposed warehouse across four levels in a highly industrial setting. Accessible landscaped play areas are provided on each level with direct connection to the playrooms. A permaculture program has been instigated across the play areas and provides a range of nature-based and activity-focused environments for both group and personal experiences.

The rooftop play area and garden has been planned around a series of edible growing zones for different companion plants. It started with orange trees and herbs but has evolved into a comprehensive list of fruit and vegetables.

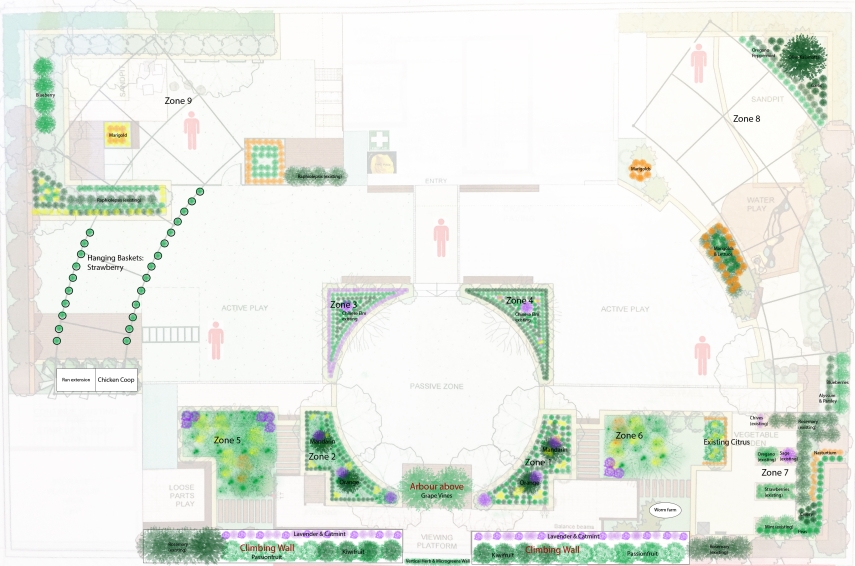

ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects. Permaculture plan (above) and a child playing in the garden (below).

The children are involved daily in planting and nurturing the plants, weeding and harvesting. Then in the kids' kitchen, they are involved in the preparation, cooking and eating of their yield. As Indira Naidoo (2011) puts it, they may not be able to grow everything they eat but they can eat everything they grow.

Permaculture strongly emphasises building mutually beneficial and symbiotic relationships (Holmgren, 2015). The garden is not generated in isolation, but through continuous and reciprocal interaction with the children, between the different plant species and with other organisms such as insects and animals. So the children are allowed to play in and around the gardens and the gardens are continually evolving and changing.

ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects. Children are involved daily in plating, nurturing, weeding and harvesting (above), while the gardens (below) continue to evolve around them.

The scope for this sort of program within primary and high schools is full of possibilities: the study of biology, geography, history, maths and English can all be enriched by onsite explorations and parallels in nature. Practical issues such as trampling and controlled access are managed through educating the children about being more aware of the plants and – from a design perspective – by the careful placement of infrastructure such as pathways, earthworks and changes in levels. These are used to create natural barriers without the need for constant input in corrective management.

ToBeMe Early Childhood Centre, Fivedock, Scott and Ryland Architects. Use of non-linear rhythmic stimuli – tree branches!

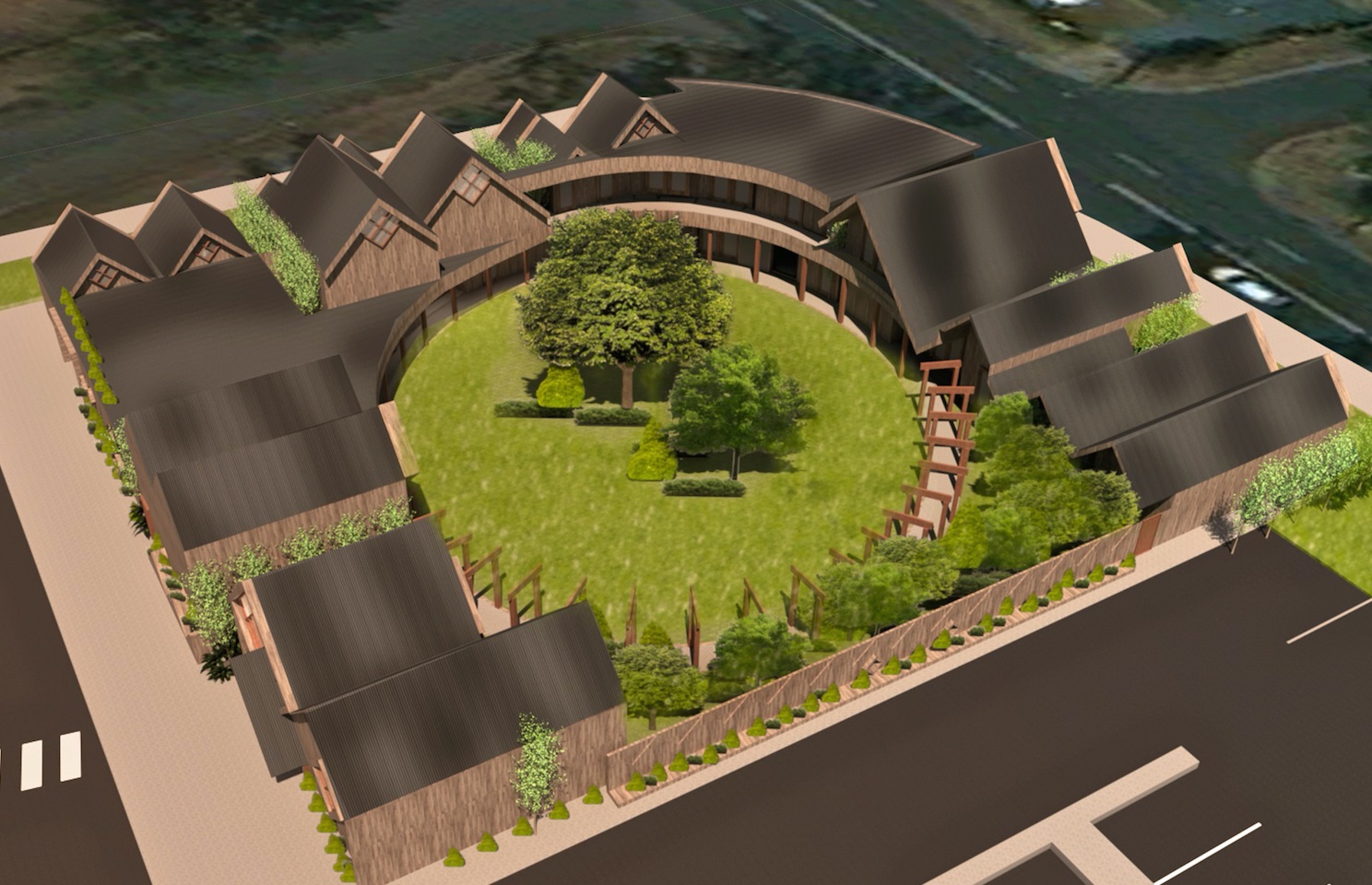

An example of an immersive biophillic school experience is the proposed but not built Eastern Creek Childcare Centre, designed by Scott and Ryland Architects for Frasers Property Australia. This stylised village is arranged as a series of domestic scaled pitched roof forms that align to the existing streetscape whilst enclosing and protecting the central outdoor play area from the road. All the playrooms have direct connection with the outdoor play area, utilising large, foldaway bifold doors. The outdoor play area faces due north to maximise each room's access to natural light.

Eastern Creek Childhood Centre, Scott and Ryland Architects, a work in progress. South elevation large picture windows with integrated planters (above); Birdseye view (below).

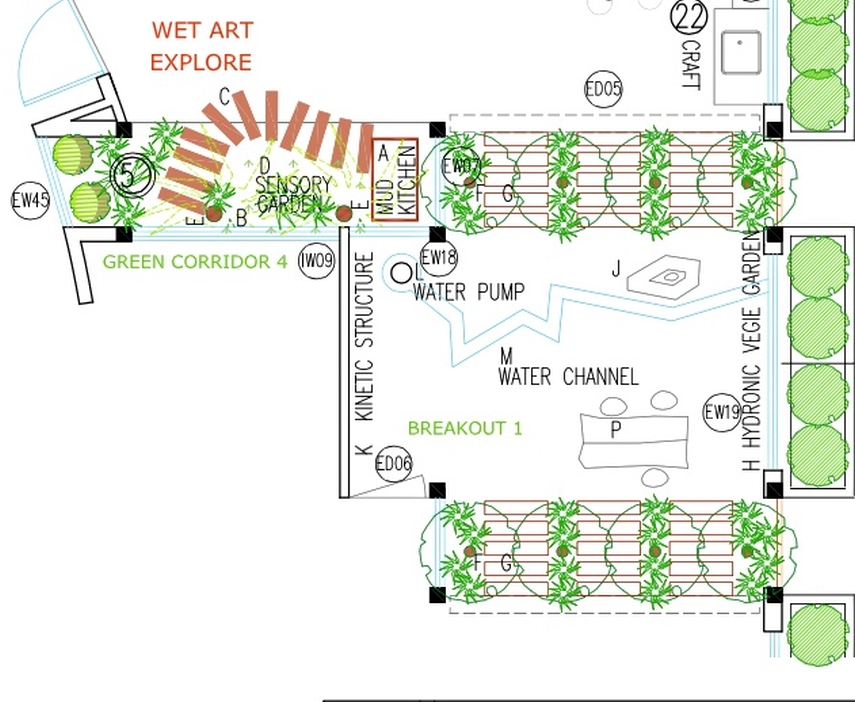

A significant feature are the addition of landscaped ‘green corridors' which are located between the playrooms, providing each playroom with a green surround effect. These are an accessible part of the indoor play area but are open to the sky and outdoor environment. Each of these corridors includes its own mini ecosystem of tall trees, under planting, rocks and water channeled through a customisable kinetic water wall sculpture and floor drain, adding a sustained biophilic, playful and harmonious setting for children's wellbeing.

Eastern Creek Childhood Centre, Scott and Ryland Architects, a work in progress. Detail plan of landscaped breakaway space between playrooms.

The design is both sustainable and biophillic, providing improved indoor air quality, natural cooling microclimates within learning spaces, maximised cross-ventilation and natural lighting. Mechanical air conditioning is minimised. Grey water storage will be used for watering plants and north-facing solar panels are implemented to reduce energy consumption and operational costs. The use of certified Australian hardwood is not just aesthetic. Timber is durable and can be recycled and re-used for future purposes.

The outdoor play area, designed in collaboration with The Gardenmakers is a major learning asset with a variety of different wild adventure play gardens, climbing structures and different types of vegetation such as mature trees, hanging gardens and low sensory gardens with variable textures, scents and colour, enabling children to learn through their senses of sight, sound, smell and touch. Each playroom is designed to be flexible in layout, with large cathedral ceilings, big picture windows and generous accessible wet areas and storage. This centre aims to be an exemplar centre with facilities above and beyond the code requirement.

Final thoughts

The benefits of designing any facility and its programs for children and young people (whether it be an early learning centre, primary school or high school) so that there is a focus on natural environments and processes cannot be overstated. Combining the advantages of the outdoors with its natural light, air, changeable stimuli and interconnectivity with the advantages of indoor areas – practical, supervisable and protected from the more extreme weather conditions – will ensure that we are giving the next generation the physical and mental health they need to thrive in life.

References

Franco, L. S., Shanahan, D. F., & Fuller, R. A. (2017). A review of the benefits of nature experiences: more than meets the eye. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(8), 864.

Holmgren, D. (2015). Permaculture: Principles & pathways beyond sustainability. Holmgren Design Services.

Naidoo, I. (2011). The Edible Balcony. Penguin.

O'Brien, L., & Murray, R. (2007). Forest School and its impacts on young children: Case studies in Britain. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 6(4), 249-265.

Scott, S. (2010). Architecture for children. Australian Council for Educational Research.

One element of creating a biophilic interior is to maximise natural light and ventilation. How could you go about doing this in your own classroom?

Author Sarah Scott says if your school is in an urban setting, natural and landscaped settings can be effectively recreated internally. Look at the four suggestions listed in the article. As a school leader, how could you work towards introducing some of these in your own context?

Sarah Scott is the author of Architecture for Children, published by ACER Press.