Why do students decide to engage with the curriculum? At ACER’s Research Conference 2025, poster presenter Peter Axford – a Senior Teacher at Malanda State High School in Queensland and a PhD candidate at James Cook University – showcased his research exploring an agency approach to student engagement with the curriculum. Here he shares the impetus for this research and how the findings influenced his own classroom practice.

In the last lesson on a Tuesday afternoon, I asked one of my year 10 students a question. His response, ‘Wait… what?’ indicated that he was carrying through the ritual of sitting quietly in class but perhaps not fully engaging in the lesson. A couple of days later, in lesson 2, I asked a year 12 student a question. Her response, ‘Hmm… what was that again?’.

They are both high-achieving students and personally interested in Geography. While I thought there was plenty of teaching and learning happening in my Geography classroom, my actions as the teacher do not guarantee student learning. I needed to ask my students what they think, and this idea informed the basis of my research.

My PhD research explored student views of engagement, and I aimed to capture the voice of every student in my classroom. I took a ‘teacher as researcher’ approach and invited senior students aged 16-19 in 3 of my classes to become co-researchers, providing purposive sampling for a case study.

Students indicated that the research should take place during class time, so we conducted class workshops and introduced an anonymous learning journal to collect their perceptions of curriculum in the moment. The discussions of agency and engagement in both the workshops and the journal provided an intimate description of the experiences that each student had, lesson by lesson. The words and phrases students used to describe their experiences then became central to my findings.

[Two students, indicating their perception of the relationship between agency and the experience of school. Image: Supplied]

Agency and the role of curriculum

In my research, I needed to properly define ‘agency’ and the ‘role of curriculum’. Students defined agency as choice, control, independence and freedom to control the surrounding conditions of the learning context. They defined curriculum as what students do; they also described what curriculum does to the individual student.

Curriculum can let kids choose what they want to learn but it often doesn’t. People won’t try if they’re not interested. Having curriculum forced on you never feels good when you feel you had no choice.

… with more collaboration between teachers and students, there may be an increase in understanding.

The student perspective (from outside the education system), looking into their own experience, means that there are also some surprising findings to come from this research. For instance, students suggested that they have a consciousness of the role of their agency in the classroom and in the wider context of the school. To engage with the curriculum these students alienated their needs to let the teacher perform their role in the classroom.

For teachers and researchers, the student perspective means that we must remember that we operate in a system where the target group are people who have lives much larger than education. Student agency, especially those aged 16-19, is well-informed and broadly experienced. Older students can bring agentive experience to endorse, subsidise or punish the teacher and the system. The best response is to enact the curriculum and build an experience of student agency through authentic self-efficacy.

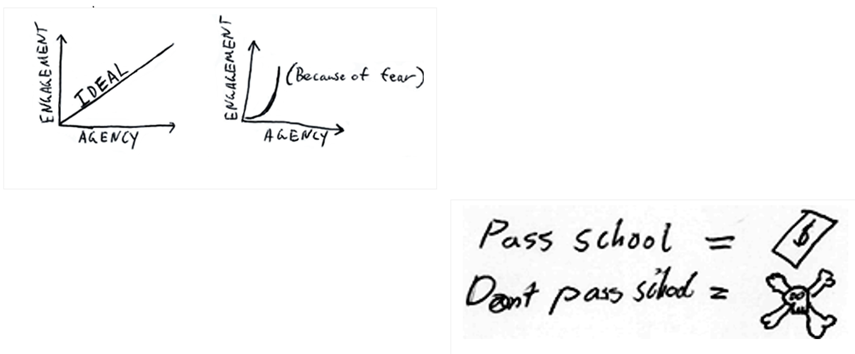

[Here the student has rephrased agency as meaning. For this student, the equation between agency, achievement and enjoyment is clear. Image: Supplied]

Rethinking my classroom practice

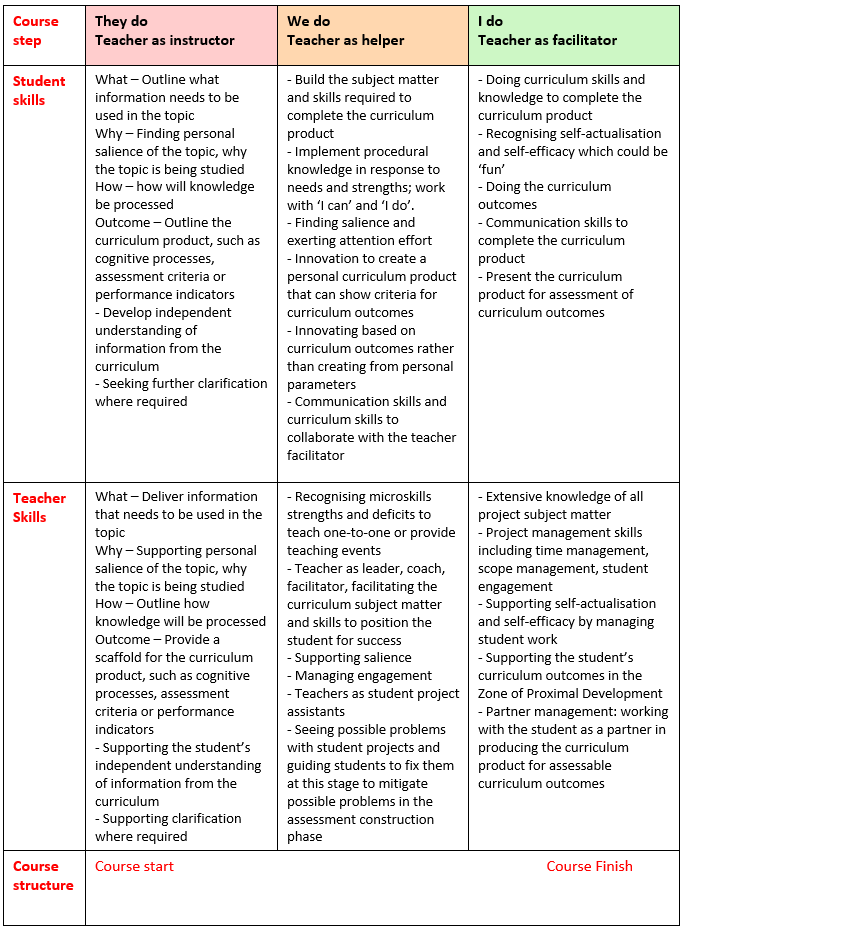

I began to rethink my role as the teacher ‘in charge’ and I started listening more. Also, rethinking the role of the student was a way of refocusing my classroom towards teaching the assessment criteria as a process completed by working together as ‘we do’. Working together with students on the assessment items for the Australian Curriculum made assignments feel more like a curriculum product rather than yet another assessment piece. As part of the second phase of my research, I tried to put a process in place to guide my teaching in light of the initial research findings (as outlined in Table 1).

Table 1: Structure for a syllabus unit moving from Teacher as Instructor to Teacher as Facilitator.

Final thoughts

The most important change in my role is the new skills that I need to develop to accommodate the students’ role in constructing the assessment. We’re bringing together 21 assignments in a Geography class, and I found myself reading about basic project management skills so I could support students successfully.

Thinking about the ‘zone of proximal development’ has been so useful for really drilling down to the individual student’s need, rather than taking a ‘sausage factory’ approach to teaching and learning.

Instead of saying ‘we’re all going to do a project on mountains’, I now give them the assessment criteria. It’s no longer what Mr Axford thinks, it’s the students having agency, looking at the assessment criteria and thinking about what they can do to meet the curriculum outcomes and, with feedback, improve further.

The Australian Curriculum requires student agency, and there is agency in the curriculum. The students in this research didn’t have that experience. When I stepped back, as far as each student needed me to, each of those faces got to do the curriculum instead of listening to me talk about it. The result has been students who feel better about themselves and their work.

Do you want to share details of successful school improvement initiatives that are making a difference to student outcomes in your own context? Get in touch with the Teacher team (teachereditorial@acer.org) today.