In the last article on writing assessment, Templestowe Heights Primary School (THPS) shared our rationale on reshaping moderation and the use of rubrics. As a measurement tool, the rubric we co-created was not producing the outcomes of consistency that we hoped for.

Dylan Wiliam, whose body of work informs considerable thinking in the area of assessment, commented in a 2015 blog post that giving students contrasting examples is more beneficial than abstract rubrics where they are left to infer the meaning of terms such as ‘uses sensory language’ (Lemov, 2015).

This was also our finding with teacher judgement. Despite the scaffold, teachers could not reliably identify where a student might sit on a model of progression. Could it be that Wiliam’s advice also applies to educators? Does the comparison of two samples provide the contrast needed to help us determine both quality and errors?

The space for an exploration of Comparative Judgement (CJ) was born. An opportunity to trial it through UK-based company No More Marking (NMM), with 25 partner schools from across Australia, was a pivotal point in the shift to an efficient technology-supported assessment.

An online algorithm merged with human judgement can create an innovative data set for schools (Christodoulou, 2020). The information provided about student writing allows us to interrogate it for gaps in learning, and shift outcomes in ways that we have never had access to before. Here’s an outline of what’s happened so far from a schools’ perspective.

Students cold write using a narrative stimulus

In week four of Term 1, over 1200 Year 3 students wrote stories using an illustration provided by NMM. These were written on sheets coded to student names and precise age in years and months. A clear set of instructions was provided and as one school noted, guidelines were ‘easy to administer, clear for all the students and efficient for the teachers to upload’, ready for the judgement process.

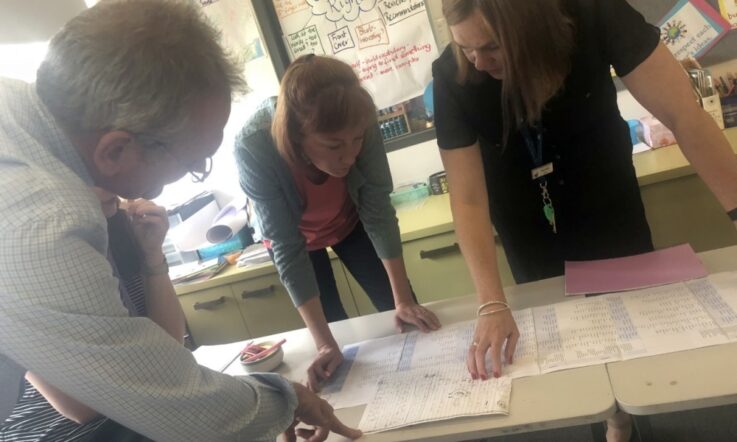

Teacher comparative judgement

Time was set aside for teachers to meet and understand what they were judging. In the case of THPS, the session began with a review of the misconceptions we have altered, into what we now consider to be the pillars of our writing instruction and learning: ‘This is what I used to think… This is what I think now…’

- We used to think that sentence work was for younger students, now we think that sentences are the building blocks of all quality writing (Hochman & Wexler, 2017)

- We used to think that students should engage in independent writing as often as possible. Now we think that meaningful sentence scaffolds, embedded in all curriculum content are rigorous tools for learning – providing teachers a much clearer assessment loop (Lemov et al., 2016)

- We used to think that grammar and punctuation was not engaging, now we think that teaching it in context with the use of retrieval, changes writing behaviours (Sherrington, 2019)

- We used to think that teaching handwriting was not essential learning, now we think that handwriting fluency leads to mastery and releases cognitive load to focus on text structure and sentence work (McLean, 2020)

While schools set up their judging frameworks differently, the process was the same for all those participating in the trial. The 371 teachers simply logged in and comparatively judged two pieces of writing at a time, thus creating a continuum that ordered the samples from the least to most selected. With 19 teachers judging, at THPS it took less than 30 minutes.

As one teacher noted, the judgement process reduced the impact of teacher bias and ‘removed the strain of reading through pages of writing and assigning a mark, as is traditionally done with rubrics’.

Release of the data to schools in the project

A week later, the data was sent to schools for download. It was an efficient process with results that allowed us to pore over individual students, the writing age assigned and the potential NAPLAN band allocated to their data. We were able to discuss gender imbalance and think collectively about the next steps that would inform our learning sequences.

The consensus in feedback from participating schools was the opportunity to see the range in writing quality and target needs identified. Teachers could see within the opening few sentences of a writing piece, key information about student ability to craft meaningful text, their use of complex vocabulary, knowledge of punctuation, grammar and commonplace errors that could be the focus of subsequent lessons. There was also consistency from the project schools in considering CJ a valuable addition to whole school assessment schedules.

How the judging works

Our approach at NMM is to set up judging so that teachers will judge writing from their school for 80 per cent of the time. For the other 20 per cent, they will judge writing from other schools: these are called the moderation judgements. So, if a teacher does 40 judgements in total, 32 of them will involve comparing work from their own school, and eight will involve writing from other schools.

Teachers never compare writing from their school with writing from another school! They either compare theirs with theirs, or other with other, so there is no opportunity for a teacher to be biased in favour of their own students.

The 20 per cent moderation judgements mean that all 100 per cent of the student writing can be standardised and placed on a consistent measurement scale.

Do the teachers agree?

When the judging is complete, we can see if teachers were in agreement. NMM’s comparative judgement dashboard provides a reliability metric that runs from 0-1, where 0 would mean that teachers were not agreeing, and 1 would mean complete agreement.

For this project, the reliability was 0.86. To understand what this means, we can make a rough conversion to a margin of error on a 40-mark scale. When we do this, we find that the margin of error is about +/- 2 marks. Extensive research on traditional marking shows that the margin of error is much closer to +/- 5 marks (Rhead et al., 2016).

NAPLAN bands and writing ages

By combining all of these judgements, we can provide each student with three key pieces of information: a scaled score, a NAPLAN band, and a writing age.

The scaled score is the first step, and it runs from about 300-700. Then, we layer NAPLAN bands on top of this scaled score. Put simply, we look at the actual NAPLAN results, take the percentage of students who get each band, and apply those percentages to our results. So, for example, about 19 per cent of students in Grade 3 get Band 6+ on NAPLAN. We therefore award 19 per cent of our participating students Grade 3. (The process is actually a bit more convoluted than this – see the NMM website for the technical detail!)

Finally, we also convert each scaled score to a writing age, which makes the scaled scores easier to understand. If you know that a Grade 3 student got a scaled score of 510, that may not tell you much. But, if you know that’s equivalent to a writing age of 8 years and 7 months, it is much more informative.

Patterns in students' writing

CJ provides schools with valuable, reliable data. But because the process is based on assessing open-ended tasks, it also provides schools with exemplification of that data too, and some fascinating insights into students’ writing.

One teacher noted: ‘… even with the same prompt, individuals made their writing individual. There was not a similar piece amongst them! Everyone brings themselves to their writing.’

Teachers were also able to identify patterns in the stronger and weaker writing, and in their feedback many mentioned the importance of sentence structure and vocabulary. This was particularly interesting for us at NMM, as these are two features that teachers in England and the United States also frequently mention. Stronger pieces of writing use more sophisticated sentence structures and more advanced vocabulary than the weaker pieces.

Our next step is to run a follow-up progress assessment with the same students to measure the progress they make over time and also the effectiveness of different interventions aimed at improving writing, perhaps including approaches that focus on sentence structure and vocabulary. We see CJ as a tool that can be used not just to measure writing, but to improve it.

Stay tuned for further updates about the Australian Writing Assessment Project in Teacher.

References

Christodoulou, D. (2020). Teachers vs Tech? Oxford University Press.

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2017). The Writing Revolution: A guide to advancing thinking through writing in all subjects and grades. Jossey-Bass.

Lemov, D. (2015, August 10). Dylan Wiliam advises: Forget the Rubric; Use Work Samples Instead. Teach Like a Champion: Doug Lemov's field notes. https://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/dylan-wiliam-advises-forget-rubric-use-work-samples-instead/

Lemov, D., Driggs, C., & Woolway, E. (2016). Reading Reconsidered: A Practical Guide to Rigorous Literacy Instruction. Jossey-Bass.

McLean, E. (2020, November 4). Handwriting instruction: What's the evidence? Emina McLean. Emina McLean. https://www.eminamclean.com/post/handwriting-instruction-what-s-the-evidence

Rhead, S., Black, B., & Pinot de Moira, A. (2016). Marking consistency metrics. Ofqual. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk//27827/

Sherrington, T. (2019). Rosenshine's Principles in Action. John Catt Educational Ltd.

Thinking about the process for moderating student work at your own school: How do you judge achievement and progress? How often do you come together with colleagues to discuss this process? How do you ensure the judgements are consistent across different teaching staff?