In learning science, students frequently apply their knowledge and skills to tasks that require multiple steps – such as solving a problem, forming an argument, or undertaking an analysis.

Providing appropriate scaffolding can be a valuable way to support students to develop and extend their knowledge and skills. One way to do this is by using worked examples.

What is a worked example?

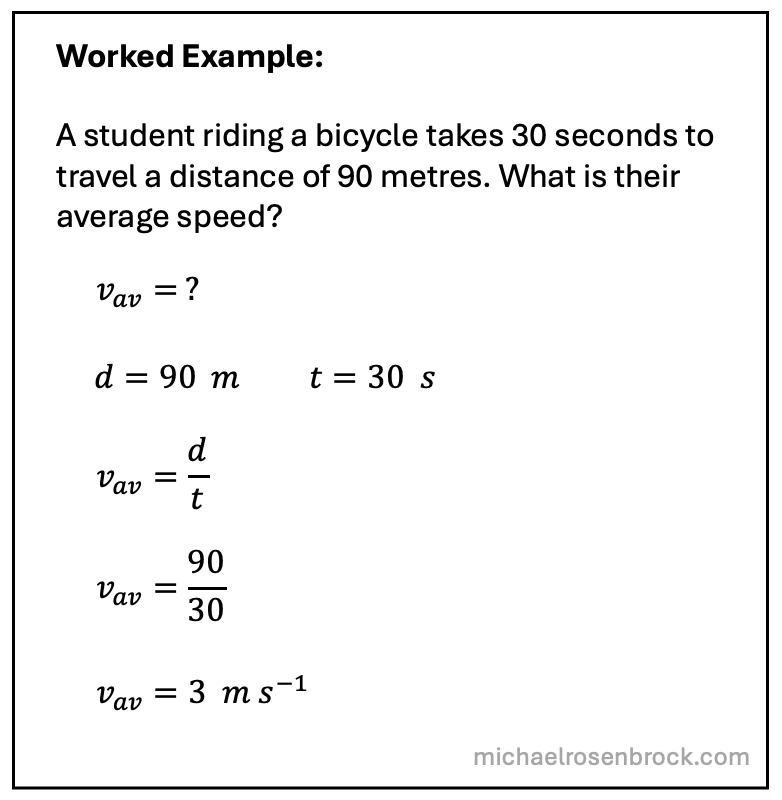

A worked example is a completed task that includes clearly and adequately explained details of the process and the outcome. This is separate to teacher explanation or ‘think aloud’ examples that may be used as a part of instruction. Rather, a worked example provides an immediate support that students can use when applying what they have learnt – most commonly when undertaking some form of independent practice.

Figure 1. A simple worked example

How do worked examples connect to research evidence?

There is a significant body of research on worked examples – mostly related to mathematics and science. Three meta-analyses on worked examples indicate that the effect on student achievement outcomes can be significant (Corwin Visible Learning Plus, 2024). Much of this research draws upon and connects to cognitive load theory (Barbieri et al., 2023; Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2018; Sweller et al., 2019).

Taking deliberate steps to optimise cognitive load can help ensure learning tasks are both efficient and effective (Education Endowment Foundation, 2021). Well planned and structured worked examples can reduce unnecessary cognitive load by providing a scaffold for student practice. This can free up working memory to focus student cognitive efforts on the key knowledge and skills that the task is intended to build.

Worked examples can have a more pronounced impact for novice learners, as the burden of unguided problem-solving is likely to overload their working memory (Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, 2018). This overload can be detrimental to completing the task as well as developing their transferable knowledge and skills.

There may be less benefit for more experienced learners. But guiding more experienced learners to be discerning in when to use worked examples may assist in avoiding any potential downside.

Worked examples can also assist with developing student metacognition and self-regulation (Evidence for Learning, 2022) in a number of ways including:

- Making a model of the thinking required visible so students can see the cognitive processes used to complete the task

- Providing a scaffold that students can access as needed when they get stuck working independently

- Enabling students to access correct and complete exemplars when revisiting or revising previous learning

- Modelling ways of organising knowledge and structuring processes

Drawing together insights from research evidence and practice, the following keys to impact can help inform the effective implementation of worked examples:

- Deliberate planning to ensure the example is targeted at the key ‘growth edge’ in the learning progression

- Aligning examples with learning objectives and success criteria

- Pre-preparing examples in advance

- Ensuring they are clear, complete and concise

- Integrating the examples as a connection between instruction and independent practice

- Pairing the example closely with opportunities to practice

- Providing ‘just enough’ detail, rather than every possible detail

- Minimising additional cognitive load in the presentation, formatting and use of examples

- Using structures and templates that are reusable and help students organise thinking

- Guiding students so that they use the examples effectively

- Supporting more experienced learners to be discerning in use of worked examples

It is also important to pre-empt ways that implementing worked examples could be ineffective or even detrimental to learning. Worked examples are not intended to replace teacher instruction; they reduce the amount of independent practice required to attain mastery.

Introducing worked examples with mistakes requires great care as these have the potential to create or reinforce misconceptions and misunderstandings (Barbieri et al., 2023; Heemsoth & Heinze, 2014). Examples with deliberate mistakes are best introduced when students are already proficient and approaching mastery. Use a different format for mistakes to make it clear they are not an example to repeat. Request students to take clear action to identify, correct and check the mistakes can also help to avoid confusion.

What do worked examples look like in science?

What would it look like if we put worked examples into practice in science teaching? Let’s look at a range of ways that worked examples can be used effectively in science.

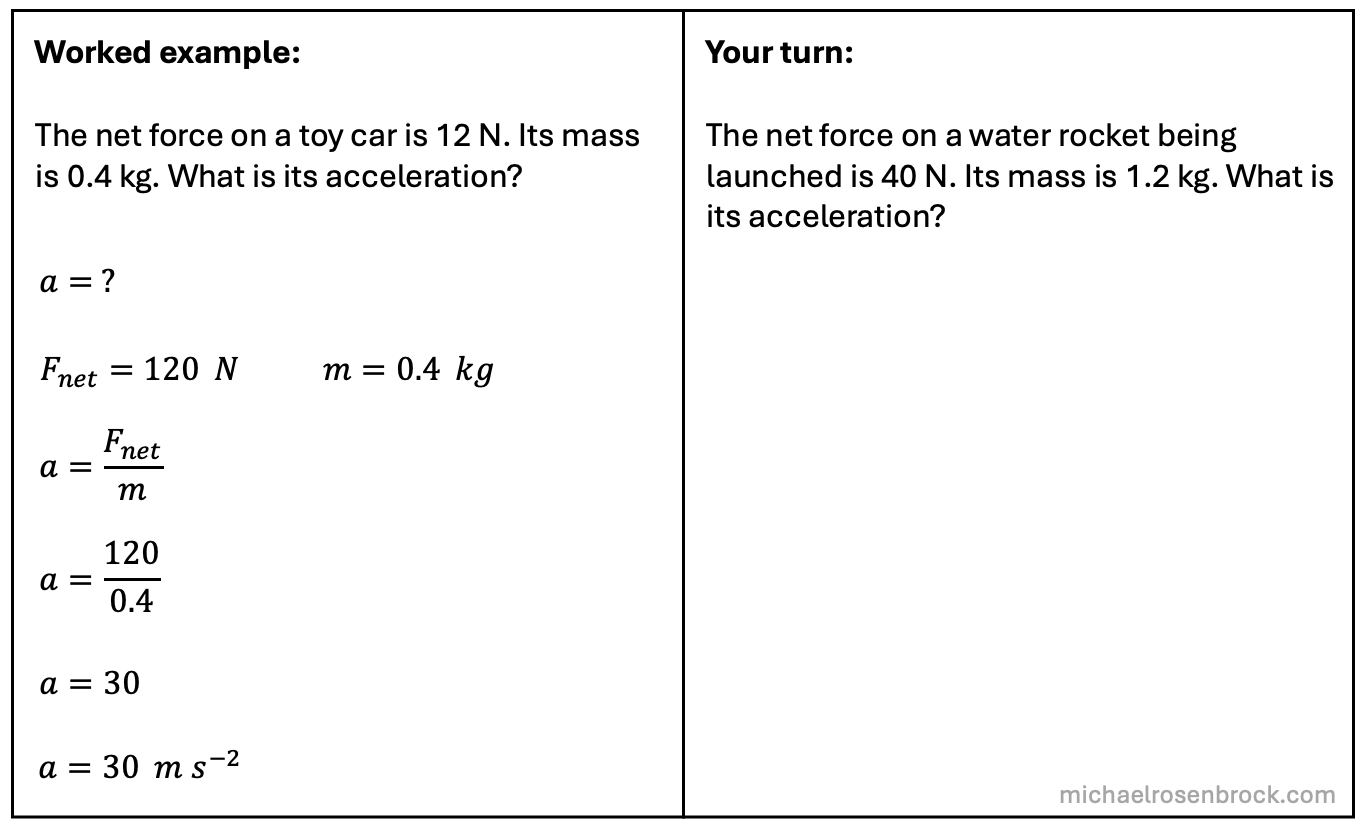

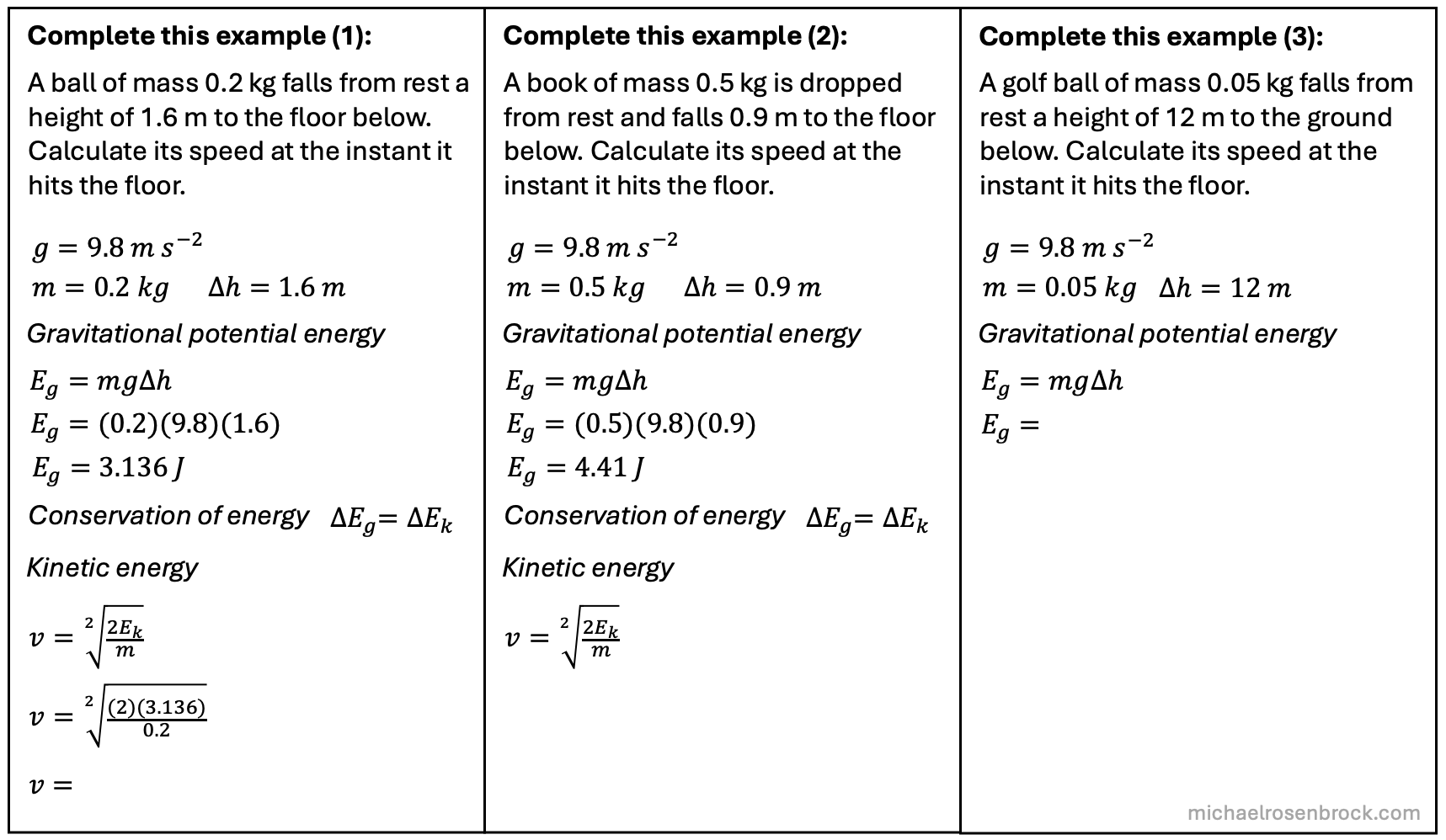

Example–problem pairs

A worked example-problem pair is as the name suggests – the direct pairing of a completed worked example with a very similar problem for students to complete. This can be effective in providing short cycles of alternation between examples and practice (Evidence for Learning, 2023a). Typically a number of pairs would be needed to practice a number of similar variations of the problem before moving on.

Figure 2. An example–problem pair

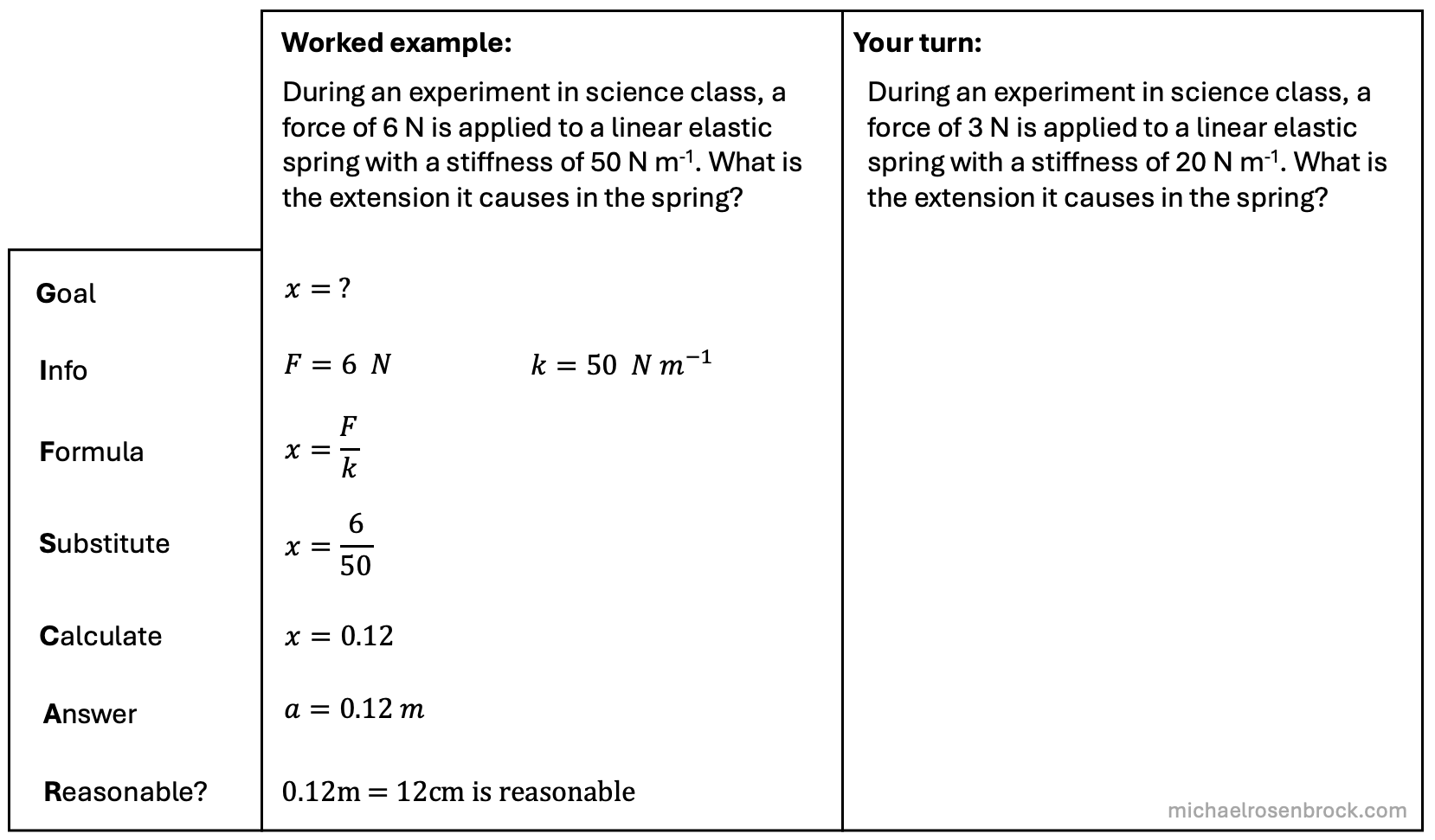

Including a process scaffold

Worked examples can be structured to model process scaffolds alongside the details of the solution. The example in Figure 3 uses the goal, information, formula, substitute, calculate, answer, reasonable (GIFSCAR) structure to help students prepare a complete response to a physics problem. It is important that additional information such as this does not overload students. Successful scaffolds should be transferable and reusable.

Figure 3. An example with a process scaffold

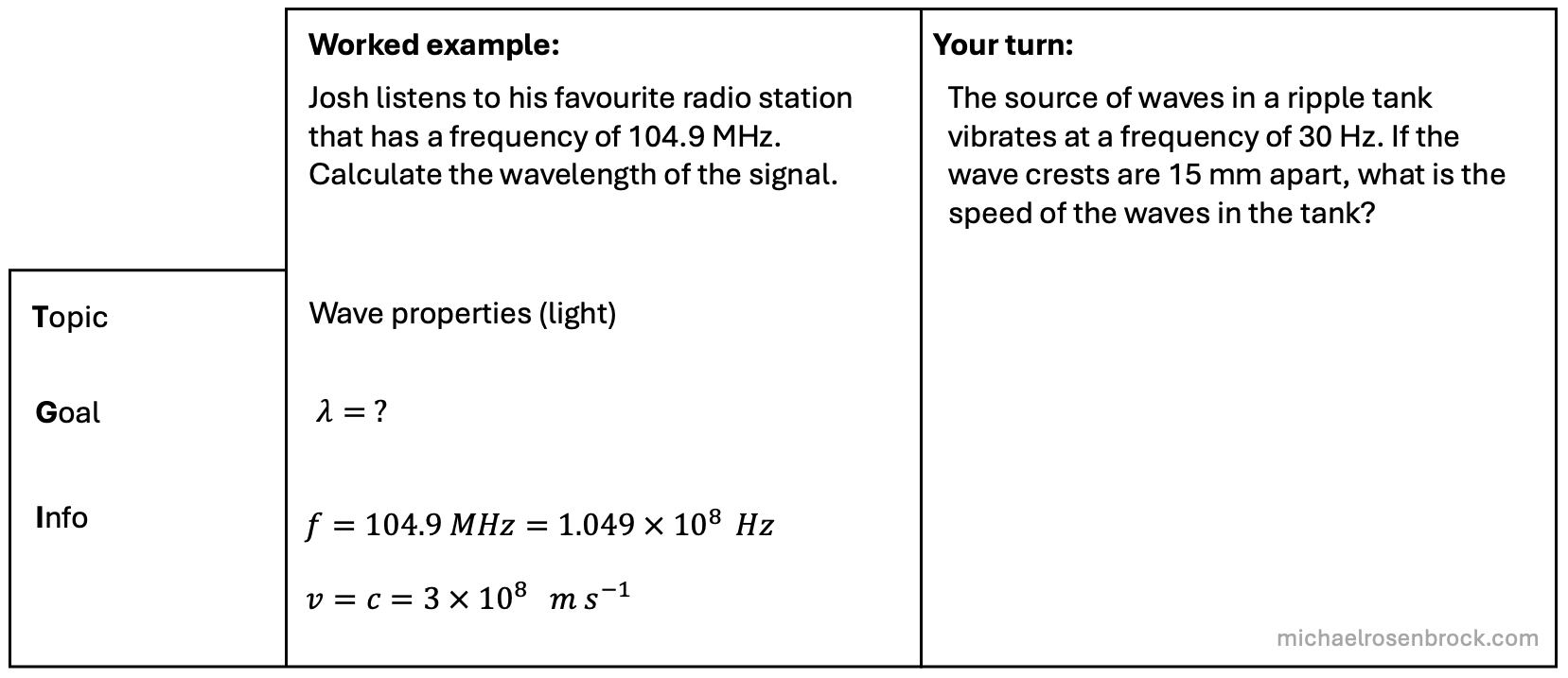

Partial examples

Examples that focus on only part of a problem can be effective when the topic is a common area of difficulty for students or when the entire problem is very long. Students often struggle getting started with worded problems, so using examples to support practice in interpreting questions can be valuable.

Figure 4. A partial example

Faded examples

Another approach to longer or more complex problems is the use of faded examples, which gradually lessens the level of support (Evidence for Learning, 2023a). This reduces the amount a student has to focus on in each example, decreasing the chances of overload. Faded examples may be used as an additional scaffold between complete worked examples and independent practice.

Figure 5. A faded example

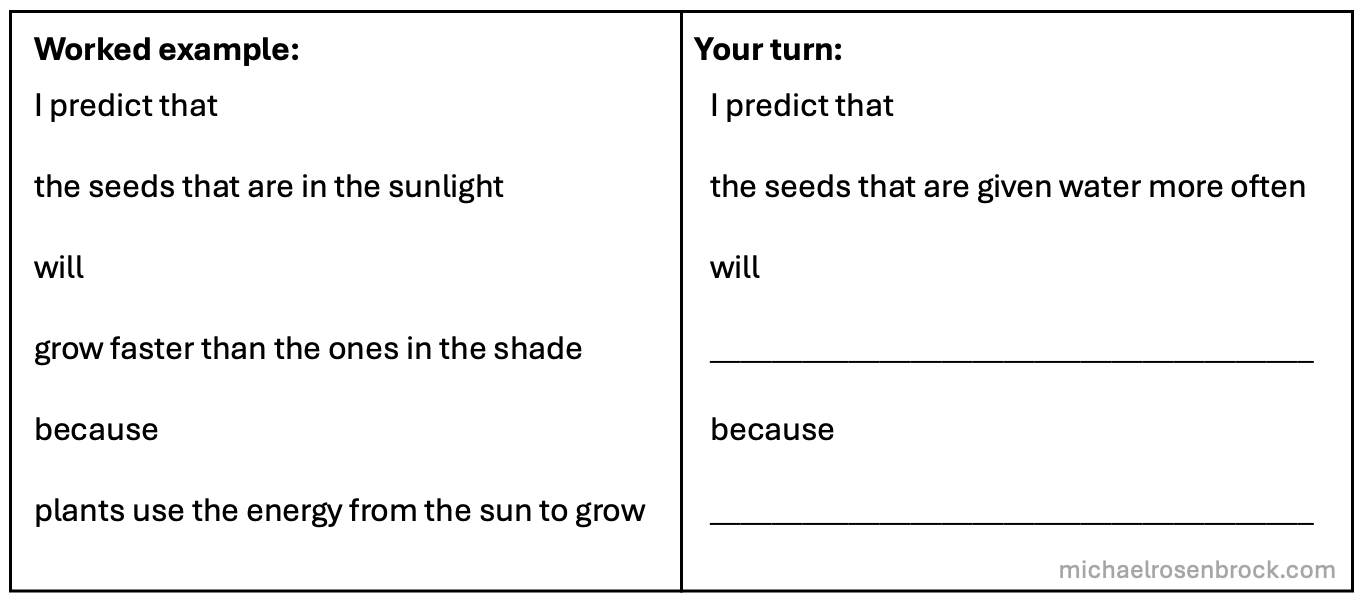

Working scientifically

Worked examples are not just for mathematical problems, they can be used in any form where they provide a valuable scaffold. The example in Figure 6 is used to support students to structure their predictions.

Figure 6. A worked example supporting prediction

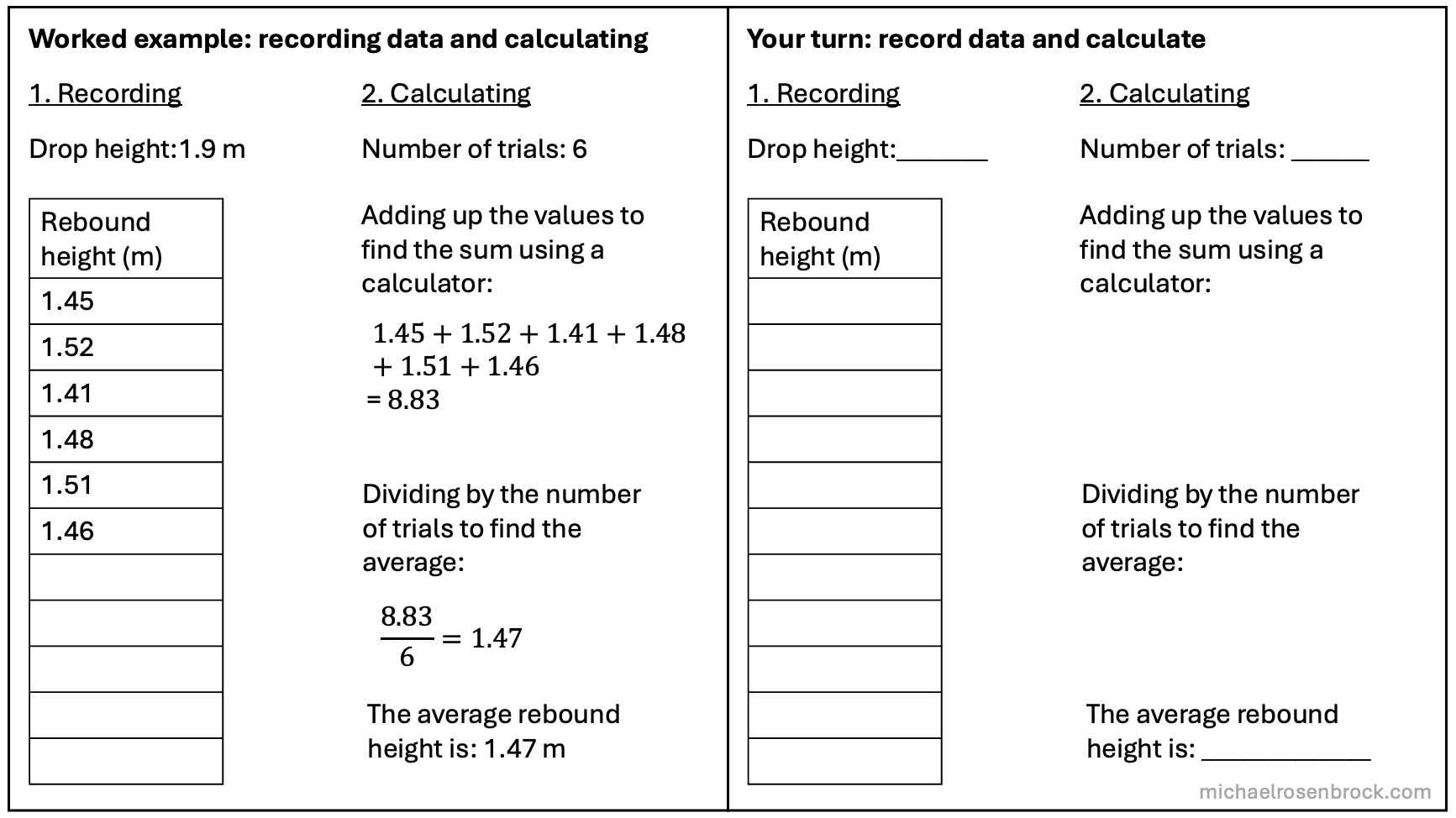

Scaffolding within a larger task

Sometimes a larger science learning task, such as a practical investigation, will require students to draw on a range of existing knowledge and skills. Worked examples can be built into the task to provide scaffolds for students to draw on existing knowledge for steps that are key to completing the task but are not the learning focus. The example in Figure 7 supports all students to effectively record data and make calculations so that they can undertake the subsequent analysis and discussion that is the task’s focus.

Figure 7. A worked example inside a larger task as a scaffold

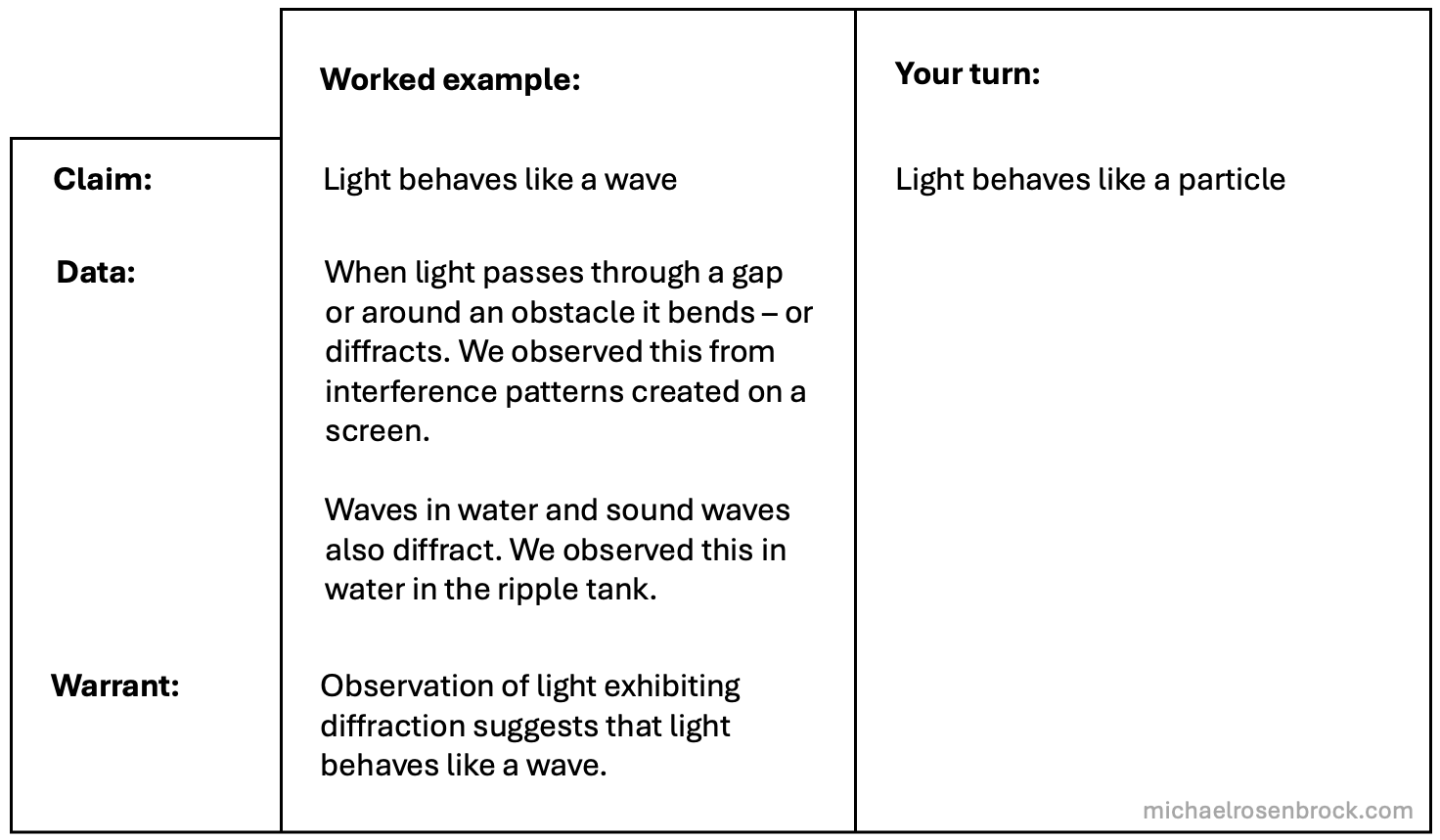

Examples of a scientific argument

Worked examples can also be used to scaffold development of scientific reasoning and expression, such as through structuring an argument. This can be done effectively in many ways, such as the claim-data-warrant approach shown in Figure 8 (Evidence for Learning, 2023b; Nuffield Foundation, 2012).

Figure 8. Scaffolding a structured argument with a worked example

Key takeaways about worked examples

- provide a bridge between teacher instruction and independent practice

- can be a very effective scaffold to support students to practice and develop their knowledge and skills

- are most effect when they reduce the load on working memory during learning tasks

- they are not just completed mathematical problems – they can be created and used effectively in many ways

References

Barbieri, C. A., Miller-Cotto, D., Clerjuste, S. N., & Chawla, K. (2023). A Meta-analysis of the worked examples effect on mathematics performance. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09745-1

Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2018). Cognitive load theory in practice—Examples for the classroom. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/about-us/educational-data/cese/2017-cognitive-load-theory-practice-guide.pdf

Corwin Visible Learning Plus. (2024, November). Visible learning – worked examples. https://www.visiblelearningmetax.com/influences/view/worked_examples

Evidence for Learning. (2022, May 31). Metacognition and selfregulated learning. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/education-evidence/guidance-reports/metacognition

Evidence for Learning. (2023a). FAME Worked examples. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/news/fame-tool-for-worked-examples

Evidence for Learning. (2023b). Improving secondary science. https://evidenceforlearning.org.au/education-evidence/guidance-reports/improving-secondary-science

Heemsoth, T., & Heinze, A. (2014). The impact of incorrect examples on learning fractions: A field experiment with 6th grade students. Instructional Science: An International Journal of the Learning Sciences, 42(4), 639–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-013-9302-5

Nuffield Foundation. (2012). Nuffield practical work for learning: Argumentation.

Sweller, J., Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 261–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09465-5

At what points in your science learning sequences would worked examples have the most impact for students?

How could you use a range of types of worked examples to support different knowledge and skills – such as problem-solving, forming an argument and analysis?

Are there opportunities to use worked examples to reduce the amount of independent practice students need to do to develop mastery, particularly in science senior schooling where student workloads can be significant?