A learning culture for the digital world – something to learn from Moscow?

While people have different views on the role that digital technology can and should play in schools, we cannot ignore how digital tools have so fundamentally transformed the world outside of school.

Everywhere, digital technologies are offering firms new business models and opportunities to enter markets and transform their production processes. They can make us live longer and healthier, help us delegate boring or dangerous tasks, and allow us to travel into virtual worlds.

Technology should therefore play an important role in education if we want to provide teachers with learning environments that support 21st century methods of teaching and, most important, if we want to provide students with the skills they need to succeed.

In the health sector, we start by looking at the outcomes, we measure the blood pressure and take the temperature of a patient and then decide what medicine is most appropriate. In education, we tend to give everyone the same medicine, instruct all children in the same way, and when we find out many years later that the outcomes are unsatisfactory, we blame that on the motivation or capacity of the patient. That is no longer good enough.

Building communities of learners

Digital technology now allows us to find entirely new responses to what people learn, how people learn, where people learn and when they learn, and to enrich and extend the reach of excellent teachers and teaching. Already today, digital learning systems cannot just teach you science, but they can simultaneously observe how you study, how you learn science, the kind of tasks and thinking that interest you, and the kind of problems that you find boring or difficult. These systems can then adapt learning to suit you, with far greater granularity and precision than any traditional classroom setting possibly can. Technology can elevate the role of teachers from imparting received knowledge towards working as co-creators of knowledge, as coaches, as mentors and as evaluators.

Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of technology is that it not only serves individual learners and teachers, but that it can build an ecosystem around learning that is predicated on collaboration. Technology can build communities of learners that make learning more social and more fun, recognising that collaborative learning enhances goal orientation, motivation, persistence and the development of effective learning strategies. And technology can build communities of teachers who share and enrich teaching resources and practices, and collaborate on professional growth and the institutionalisation of professional practice.

Combining data with collaboration

There is another angle from which to consider technology in education. Data can support the redesign of education as it has already done in so many other sectors. Imagine the power of an education system that could share its collective expertise and experience through new digital spaces. But throwing education data into the public space does not, in itself, change how students learn, teachers teach and schools operate. That is the discouraging lesson from many administrative accountability systems. Turning digital exhaust into digital fuel, and using data as a catalyst to change education practice, requires getting out of the ‘read-only' mode of our education systems, in which information is presented as if inscribed in stone. This is about combining data with collaboration.

We should ask ourselves why schooling is still so far from delivering on these promises, and it is clear that if we continue to dump technology on schools in a piecemeal way, we won't be able to realise technology's potential. Perhaps we should stop seeking the ‘killer app' or the ‘disruptive' business model that will somehow turn existing practices upside down. Perhaps, instead, we should learn how to identify, interpret and cultivate systemic capacity for learning with technology across the entire ecosystem of schooling.

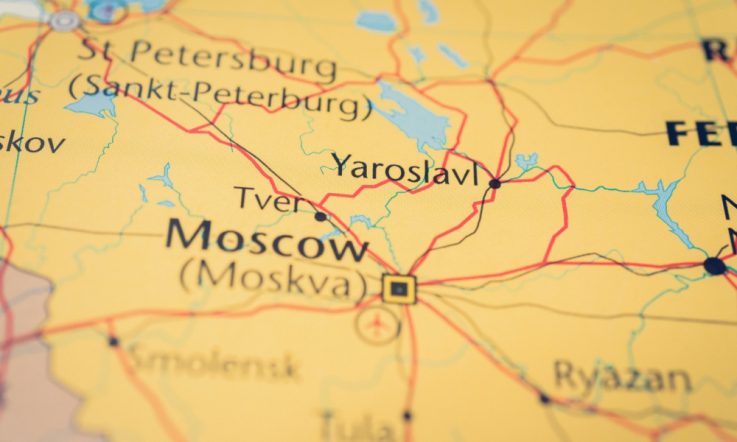

Something to learn from Moscow?

In some places, there has been a silent revolution where exactly that is happening. Over the last years, the city of Moscow has digitised virtually every aspect of its instructional system, and the key differentiator of the city's approach is not the specific technology, but the support and incentives that have shifted the role of students, teachers and parents from being consumers of educational services towards becoming designers and co-creators of educational content and learning methods.

In the schools I visited I saw teachers using a digital platform to develop and share engaging instructional material. That in itself is not unusual; what made it different was that the platform was not school-based but available across the entire city, and that it was integrated with reputational metrics. The more other teachers download, or critique or improve lessons, the greater the reputation of the teacher who shares them. Teachers have already contributed over 300 eTextbooks, 70 000 interactive applications and close to 40 000 lesson scenarios which, being built around a common lesson structure, can easily be reconfigured and adapted in the classroom. The teachers I spoke with saw themselves as proud designers of imaginative learning environments, who scaffold problem inquiry and help students see the value of learning beyond content knowledge acquisition.

The city is giving out grants to teachers and schools in order to encourage and support the development and curation of high quality instructional material. Most of these are in the order of US$ 400–700, not much, but enough to signal that teachers contribute value to the system. In this way, Moscow is creating a giant open-source community of teachers and unlocks teachers' creativity simply by tapping into the desire of people to contribute, collaborate and be recognised for their contributions. And teachers can spend more time on this, since routine administrative and instructional tasks that take valuable time away from teaching are being handed over to technology.

This is how technology can extend the reach of good teaching, recognising that value is less and less created vertically, through command and control, but increasingly horizontally, by whom we connect and work with. One teacher can now inspire hundreds of thousands of learners, and at the end of the school year, teachers don't just see how well they taught their own students, but also what contribution they have made to advance the teaching profession and the wider education system.

Most importantly, student learning is becoming personalised, adaptive and more engaging, with lesson scenarios that range from animated digital content, through interactive tasks, up to learning in virtual laboratories where students design, conduct and learn from experiments, rather than just reading about them. The digital lessons enable students to access specialised materials in multiple formats and in ways that can bridge time and space. I tried to configure the planets around the sun in a VR-based environment, and although I failed, I can now remember and visualise their correct sequence, something my own teachers failed to teach me over many years.

In this way, technology is enhancing experiential learning, facilitating hands-on activities and delivering formative real-time assessments. And the e-school does not end with the school day, students can access the resources at home, complete their homework and other assignments, and assess their learning progress interactively. Not least, the e-school is connecting parents with education, facilitating communication with teachers, helping parents understand and follow their children's timetables and learning progress, and getting invitations to educational activities in the city.

I meet many people who say we cannot give teachers and education leaders that kind of professional autonomy because they lack the capacity and expertise to deliver on it. There may be some truth in that. But simply perpetuating a prescriptive model of teaching will not produce creative teachers: those trained only to reheat pre-cooked hamburgers are unlikely to become master chefs.

By contrast, when teachers feel a sense of ownership over their classrooms, when students feel a sense of ownership over their learning, that is when productive teaching takes place. Technology is not the sole answer to this, but it is an essential part of the answer.

The city of Moscow hasn't invented any of the pieces, nor is it the first to deploy them. All it has done is to put the pieces together within a coherent vision and at scale, so that the various parts of the school system are moving in the same direction. For many other school systems, that still seems an unsurmountable challenge.