Last term, we shared the 2025 winners of the Australian STEM Video Game Challenge. This free, annual video game development challenge invites students in years 3-12 across Australia to design and develop a video game based on a given theme in teams of 1-4. Team mentors (typically a school staff member) support students and their games are judged by teachers and industry experts.

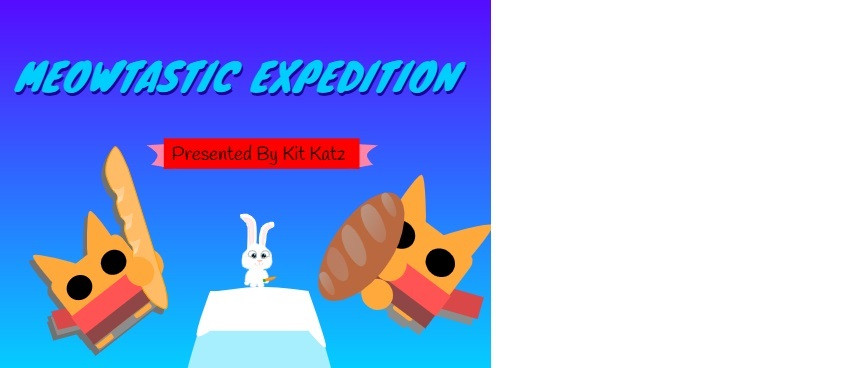

One of the winning teams for 2025 was KitKatz – 4 students from West End State School in Brisbane who took out the win for the year 3-6 Scratch category with their game, Meowtastic Expedition.

They were supported by their team mentor, teacher aide David Jeffery. West End State School has been participating in the challenge since 2018. In 2025, 23 teams entered from our school. In this Q&A, David Jeffery shares how the challenge is run at their school, the opportunities it provides to students, and his advice for other schools wanting to have a crack in 2026.

Can you tell me about your role at West End State School, and the school context there?

I’m a teacher aide at West End State School, a large inner-city primary school in Brisbane. My main role is providing support to highly capable learners, but I also run our Tech Hub – a room full of tech from laptops and iPads to robotics and 3D printers. The Tech Hub is designed to encourage self-guided extracurricular exploration. I think it’s the classroom I dreamed of being in as a nerdy 80s kid.

Congratulations on having a winning team for this year’s STEM Video Game Challenge! What does it mean to you and the students to be recognised in this way?

Thanks! The KitKatz team couldn’t really believe it. They got so engrossed in making Meowtastic Expedition they kind of forgot about the competition side of things. Once they’d submitted the game and put their heads above water again, they realised they’d made something pretty special. They checked every day to see if the number of plays had gone up, and what comments were left. It’s a very Gen Alpha way of feeling validated!

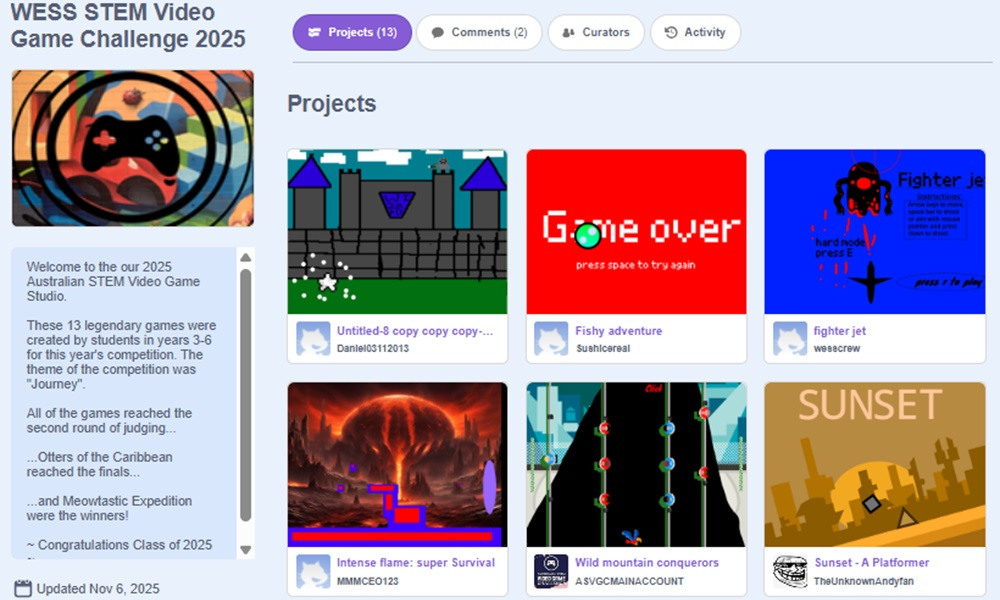

I think every team in our school that entered the challenge had a similar moment when they received their judging feedback. The judges recognised the amount of work the teams had done and celebrated their achievements, big or small. West End State School makes sure every team is recognised by their peers, too. All of the teams that completed a game are recognised on a Legends board, and we have a Scratch studio where the games can be played by their classmates and families. They’ll all attend a video game themed breakup party in term 4.

It means a lot to students who didn’t participate as well. Hundreds of kids access our Tech Hub at playtime each week, and they’ve all been keenly following this year’s competitors. Whether a team goes deep into the competition or not, everyone sees how the teams organise and how hard they work. They see the daily successes and failures, and as the games take shape they are the first to try them.

So, every stage has been a celebration. Teams were cheered every time they progressed to the next round of judging. New posters went up announcing the latest results. The video game challengers become celebrities, and the tension was high when our school made the finals. When the win was announced, the principal came to the Tech Hub and danced to Crazy Frog’s We Are The Champions with the students!

Why does your school participate in the challenge? What opportunities does it provide to students?

Technologies is a tricky subject area in primary schools. Tech’s a great enabler, and the national curriculum does teach concrete skills and understandings. But I believe the best learning happens when there are no guide rails and students learn skills because they need them, right now, to meet their own defined goals. I think that’s a major opportunity the challenge provides.

I love seeing the ‘I’m bad at maths’ students feverishly crunching the numbers to solve a gravity problem in their game. They don’t even realise they just taught themselves algebra and the laws of motion! And the coding concepts in the curriculum, like branching or iteration, become crystal clear when you need to decide if Pac-Man ate the power pill or not.

The same happens with the art, music, and storytelling in the games. There’s no pre-defined goal except what’s set by the team’s imagination and ambition. And when they find and master tech tools to enable themselves, they often find they can produce something beyond what they imagined.

As our participation has grown there has been a snowball effect. Experienced challengers pass on their knowledge and skills to the next generation. The STEM Video Game Challenge has become an opt-in, self-guided learning community.

It certainly seems like the challenge is a big part of your school culture, then. How do you embed it into the school year? Where is time allocated in the timetable for students to work on their games?

We kick it off with a launch in term 1. I provide each classroom teacher with some text, pictures and links and they tell their class about the challenge. Posters in the eating areas direct students to the Tech Hub at play time to find out more. That’s when new students see the teams already working on games and get to play the entries from the previous year’s teams.

From that point on, the challenge is embedded outside of the classroom. It’s done this way because I’m a specialist teacher aide, not a teacher. My job description is to enrich the curriculum and not to deliver it. In most subject areas that’s done with term-long courses that extend the ideas in the curriculum, but this doesn’t work with Technologies for the reasons mentioned earlier. A good student can get an A for Technologies with little skill or understanding, because they are organised and disciplined and can produce whatever product the assessment demands. Meanwhile, the students who are already learning by themselves how technology empowers them, and deeply understand the systems they use, can fly under the data radar.

The extracurricular way we run the challenge allows students to choose their own adventure and enrich themselves, whatever their level. The hidden tech superstars are drawn to it like a magnet and can blow past the curriculum and go to infinity and beyond. For the beginners and the tech-curious, it’s an exciting entry point where they can learn through experimentation and take risks without having to shape their products around assessment. There’s also a substantial creative cohort for whom it’s a vehicle for self-expression and storytelling.

What do the students think of the challenge?

It may seem strange to my generation, but they see the challenge as something ‘more real’ than school. Watching YouTube tutorials, sharing prototypes and assets in the Cloud, and publishing something online; for digital natives these are actions that connect them to the world outside their local space. These are very significant community spaces for them. This is the ‘go out and play’ they keep getting asked to do!

They also see the challenge as a scaffold that enables them to create something important to themselves. Modern students have so many things competing for their time and attention. A long-term project is really hard to commit to and stay focused on. Participants in the STEM Video Game Challenge are supported by the team structure of the task, along with the emphasis on planning, and it empowers them to create something bigger than themselves.

For school staff who may be thinking they’d like to get involved in the challenge next year, do you have any words of wisdom or advice for getting started?

Jump right in, you won’t regret it. Start with a single team or find other interested staff to join you. I’d recommend mentoring the team/s yourself the first time you take part. Seeing the challenge from within will really help you to figure out the best way to make it work in your school.

Don’t be put off if you don’t have any technical skills. There’s plenty of good resources provided by the organisers, including a full curriculum plan, and there’s much more online – point your students in that direction and let them go. You’ll be surprised at what skills they’ll pick up all by themselves.

It’s a big challenge, and many teams won’t make it to the finish line, but celebrate what you achieve anyway, and then recalibrate. Our first ever team didn’t end up with anything to submit, yet they were chomping at the bit to try again; and this time both the team and I had a better idea of how to get there and the motivation to make it happen.

If you can, create a space where everybody involved meets up regularly. It can be physical or virtual. For us it’s a Teams channel and the Tech Hub at lunchtimes. Magic happens when people connect and the space you create will soon have a life of its own.

The STEM Video Game Challenge is one of the most rewarding things I’ve done as an educator. Seeing students grow is the main joy we get from our vocation, and the challenge is a greenhouse of the highest order. Add in the confidence that comes from genuine student self-expression and it’s truly wonderful.

The STEM Video Game Challenge has been run by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) since 2014. To stay up to date with the 2026 Australian STEM Video Game Challenge dates and announcements, and for more information and mentor resources, visit the website.