School resourcing: What hinders quality instruction?

It was recently reported in the media that, in a survey of about 1000 parents, 88 per cent rated the level of resources available at their children's school as at least adequate. Of course, parents' views are only one perspective.

The OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), on the other hand, asks quite specific questions about resourcing of those right at the chalk face – teachers and principals. In Australia, just over 3500 teachers and 230 principals working in lower secondary schools participated in the TALIS study. The sample of schools was drawn to be representative of state, sector, and geographic location.

Principals' views

Principals were asked about the extent to which they felt particular school resource issues hinder their school's capacity to provide quality instruction (not at all; to some extent; quite a bit; a lot). There were 15 resource issues listed, and, by and large, Australian principals responded more positively than those across other OECD countries, on average.

The four top issues for Australian principals were a shortage of time for instructional leadership, which was reported by 28 per cent of principals as hindering their school's capacity to provide quality instruction quite a bit or a lot, followed by a shortage of teachers with competence in teaching students with special needs (18 per cent of principals), a shortage of vocational teachers (17 per cent of principals) and a general shortage of qualified teachers (16 per cent of principals).

However, the picture depends on whether their schools has a high or low proportion of disadvantaged students. One of the TALIS background questions asked principals about the proportion of their students from socioeconomically disadvantaged homes and, for the purposes of comparisons, this creates the OECD groupings of ‘more advantaged' schools, in which fewer than 30 per cent of students come from socioeconomically disadvantaged homes, and ‘disadvantaged' schools, in which more than 30 per cent of students come from such homes.

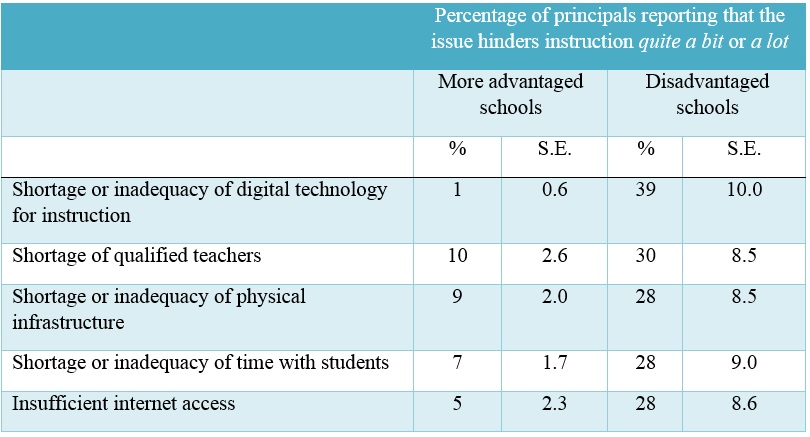

Based on further analysis of the data, it was found that for most of the 15 resource issues, fewer than 10 per cent of principals of more advantaged schools identified any as hindering the provision of quality instruction quite a bit or a lot. Three of the four top issues already identified were equally issues for principals in both advantaged and disadvantaged schools. However, the general shortage of qualified teachers, while an issue for all principals, was significantly more of an issue with principals of disadvantaged schools. There were four other issues for which there were significant differences between the responses of principals of disadvantaged and more advantaged schools, as shown in Table 1.

The most striking difference between advantaged and disadvantaged schools is in the area of digital technology for instruction – an issue in almost four in 10 disadvantaged schools but one in 100 advantaged schools. The shortage of qualified teachers is clearly a major issue for principals of all schools, but much more for principals of disadvantaged schools.

Table 1: Shortages of school resources that hinder quality instruction in Australian schools, by school socioeconomic level

Teacher's views

One of the supplementary questions included in the Australian version of the TALIS teacher questionnaire asked teachers to rate the extent to which they felt that their capacity to provide quality instruction to the target class was hindered by nine different factors.

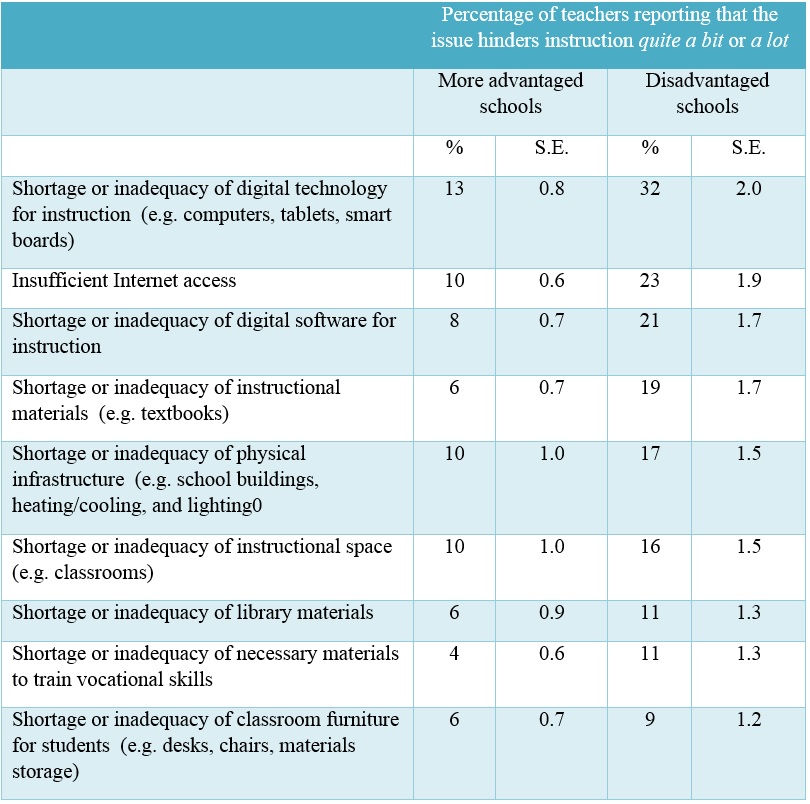

While principals have a school-wide perspective, there was substantial agreement between principals and teachers on the issues they face. Among all Australian teachers surveyed, as with principals, technology was the most commonly identified resource issue. Seventeen per cent of teachers reported a shortage or inadequacy of digital technology and 13 per cent reported insufficient internet access as impacting on their capacity to provide quality instruction quite a bit or a lot. However, on all nine factors there were significant differences between teachers in more advantaged schools and those in disadvantaged schools (Table 2).

The technology issues identified by all teachers were particularly an issue for those in disadvantaged schools, with almost one-third reporting a shortage of digital technology for instruction, almost one-quarter that there was insufficient internet access, and one-fifth that there was a shortage or inadequacy of digital software for instruction. However other, more basic issues were identified as hindering instruction by a substantial proportion of teachers in disadvantaged schools.

One-fifth of teachers in disadvantaged schools reported a shortage or inadequacy of instructional materials (such as books), and 17 per cent reported that a shortage or inadequacy of physical infrastructure (such as school buildings, heating/cooling) hindered instruction quite a bit or a lot. These are very basic requirements for schools in a modern, wealthy economy such as Australia's, and while there has most definitely been a large increase over the years in funding to schools, TALIS data clearly shows that resourcing continues to be a challenge.

Table 2: Australian teachers' perceptions about issues hindering instruction, by school socioeconomic level

School resources and student achievement

These data, from teachers and principals in Australian schools, present quite a different picture than that reported from parents. With gaps of about three years of schooling evident between the PISA scores of advantaged and disadvantaged schools, it is time to address the resources that are lacking in disadvantaged schools.

Indeed, policymakers should focus on ways to reduce inequality in Australia's education system, such as seeking to resource all schools according to their students' needs. While certainly not the complete story, it is difficult to imagine trying to achieve excellent academic results in a situation in which there are shortages or inadequacies of resources at such a basic level.

References

Thomson, S., & Hillman, K. (2019) The Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018. Australian Report Volume 1: Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. Australian Council for Educational Research. Retrieved from www.acer.org/talis