In our annual reader survey, when we asked what you’d like more support and Teacher content on in 2026, ‘research news’, ‘literacy’ and ‘inclusion’ were 3 of the most requested topics. Recent research from Edith Cowan University highlights a lack of disability representation in children’s picture books. In today’s article we speak to lead researcher Associate Professor Helen Adam about the study findings, and practical advice for K-12 teachers when it comes to selecting books for a school or classroom library.

Picture books are an important early years resource for children to learn about themselves and the world around them. They can also be a teaching tool for promoting inclusivity, so when you’re thinking about selecting resources, choosing diverse books is a good starting point.

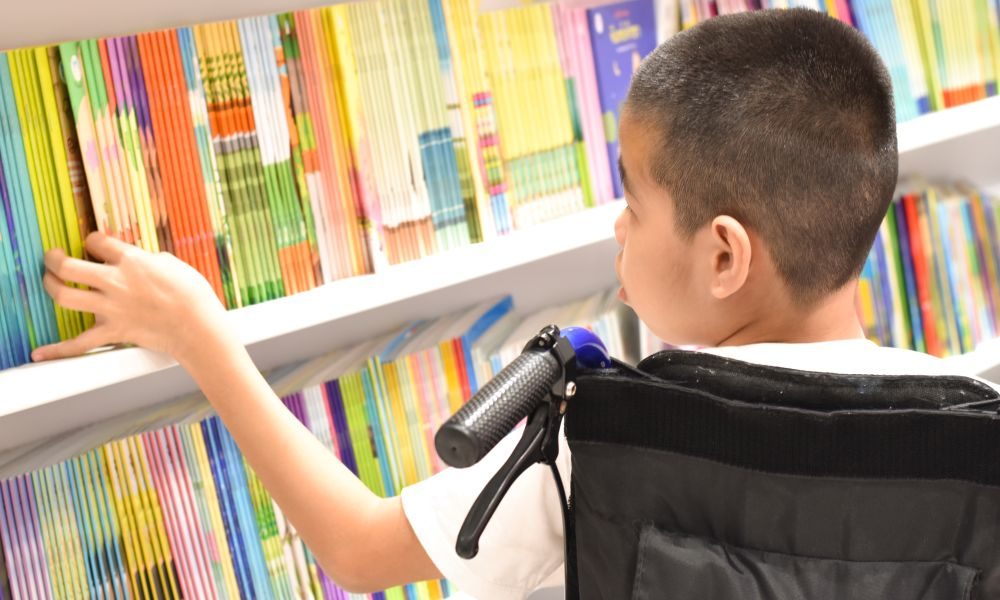

Researchers from Edith Cowan University’s (ECU) School of Education recently analysed 90 award-listed Australian children’s picture books and found a critical gap – an almost total absence of disability representation. In fact, only one of the 90 books portrayed a character with a physical disability – even then, the child was a background character on one page and having their wheelchair pushed by a child without a disability on another.

Details of the study have been published in the journal Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years (Adam et al., 2025). Associate Professor Helen Adam tells Teacher magazine the research team were shocked, but not surprised, by the findings.

‘We've been examining diversity in Australian children's picture books for several years now, and while we've documented gaps in cultural diversity and family representation, we are saddened to see disability representation to be virtually non-existent.

‘Given that 7.6% of children aged 0-14 have a disability in Australia, we would expect to see at least some books reflecting this reality among 90 award-listed titles. Finding only one book – and in that book, the disabled child appears as a background character, and in another image as the passive recipient of help from an able-bodied child – really highlighted how invisible children with disabilities are in our literature.’

She points out that it’s a requirement of Australia's Early Years Learning Framework for educators to ‘plan experiences and provide resources that broaden children's perspectives and encourage appreciation of diversity, including disability. We can't meet this mandate if the books simply aren't there.’

The research team stress it wasn’t an issue with the quality of the books and the writing – they were all award-listed. ‘These are well-written, engaging books with important themes and messages. That's partly why they're award-listed,’ Associate Professor Adam says. ‘The issue isn't the quality of the writing; it's what's missing from the narratives. And that's important to note because it means the solution isn't about lowering standards – it's about broadening whose stories get told within high-quality literature.’

The researchers report ‘encouraging signs’ in other areas of representation compared to their analysis in previous years – 41% of the books depicting families feature sole-parents; multigenerational households were also present; and there was movement towards more culturally diverse representation. ‘So, we are seeing gradual progress in some dimensions of diversity – which makes the complete absence of disability representation even more glaring by contrast,’ Associate Professor Adam says.

Mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors

Explaining why it’s important that students from marginalised groups ‘see’ themselves in the books they have access to at school, Associate Professor Adam says the work of Rudine Sims Bishop has guided much of her own research. ‘Bishop argued that children need books that serve as mirrors – reflecting their own experiences and identities back to them – as well as windows into others' lives and sliding glass doors they can step through to experience the world from another's perspective.

‘For children with disabilities, not seeing themselves represented in picture books sends a powerful message: that their experiences aren't valued, that they don't belong in the narratives we tell about childhood and community. This invisibility can significantly damage their developing sense of self and belonging.

‘These children are already navigating a world designed primarily for those without impairments – when the literature they encounter compounds that invisibility, it reinforces the notion that disabilities are exceptional rather than an integral part of human diversity.

‘Children with disabilities face unique challenges, and seeing characters who navigate similar experiences – who are portrayed as complex, capable individuals rather than stereotypes or objects of pity – provides crucial affirmation and models for understanding their place in the world.’

Associate Professor Adam adds books featuring disabled characters helps all students develop accurate and respectful understandings and helps challenge ableism.

Of course, simply having the books in your classroom or school library is one part of the equation. Educators also need to use these resources as prompts for further discussion.

Practical advice for K-12 teachers when selecting books

Associate Professor Adam says building a well-rounded representative school or classroom library can’t just be a ‘random grab’ or based on award shortlists alone.

‘Whilst book awards recognise excellence in writing and illustration, they may be based on attributes other than representation of our diverse society. So, educators need to select books with a measured eye to respectfully include all.’ Here's her practical advice.

Be intentional and systematic in your selection: Don't wait for diverse books to appear - actively seek them out. This means going beyond award lists and popular titles to find books that represent the full spectrum of human diversity, including disability.

When selecting books featuring disability representation, be mindful of: The type of portrayal - Avoid books where disabled characters are portrayed as weak, dependent, unproductive, objects of curiosity or violence, or merely vehicles for other characters' growth. Look for books where disabled characters are rich, complex individuals with their own agency and narratives.

Stereotypical labels and tropes - Be cautious of books that create an atmosphere of 'strangeness' or 'otherness,' reinforcing normative standards. Avoid inspiration porn – the trope where disabled people are portrayed as inspirational solely because of their condition. These representations reduce individuals to single characteristics rather than presenting them as complex people.

Look for strength-based representations: Recent work by Hayden and Prince (2023, 2024) provides excellent frameworks for evaluating disability representation in children's picture books. They advocate for portrayals where disabled children are rich and complex characters, everyday people within books, not just main characters defined solely by their disability.

Consider #OwnVoices: It's time we see more diversity in the authorship of children's books, where authors' own lived experience is reflected in the stories they tell. Research by Booth and Lim found that of 284 children's picture books published in Australia in 2018, only one had been written by an author with a disability. Seek out books by disabled authors where possible.

Remember that representation matters across all types: Whilst our study focused on overt, visible disabilities, remember that intellectual impairment and neurodiversity may be less visible in picture books but are equally important to represent.

Use books as conversation starters: Simply having diverse books isn't enough – whilst children can gain much serendipitously from books, it's conversation that can delve into issues that may not be simply noticed. This means choosing books with multilayered storylines and characters that afford these conversations.

Audit your collection: Take stock of what you currently have. How many books feature disabled characters? How are they portrayed? Where are the gaps? Then make a plan to fill those gaps deliberately.

Final thoughts

‘The evidence is clear,’ the academic advises, ‘educators need to intentionally seek out and evaluate well-written books that accurately represent the lived experience of disability and incorporate these into daily practice alongside other books reflecting the full and rich diversity of lived experience in our society. This isn't about tokenism or ticking boxes – it's about creating learning environments where all children feel valued and represented.’

References

Adam, H., Murphy, S., Urquhart, Y., & Ahmed, K. (2025). The absence of disability representation: A critical gap in children’s picture books. Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years, 30(2), 18–20. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.T2025061000010801537025028

Booth, E., & Lim, R. (2021). The Illusion of Inclusion: Disempowered “Diversity” in 2018 Australian Children’s Picture Books. New Review of Children's Literature and Librarianship, 27(2), 122-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2021.2020574

Hayden, H. E., & Prince, A. M. (2023). Disrupting ableism: Strengths-based representations of disability in children’s picture books. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 23(2), 236-261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798420981751

Hayden, H. E., & Prince, A. M. (2024). “Not a Stereotype”: A Teacher Framework for Evaluating Disability Representation in Children’s Picture Books. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 63(1), 5. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol63/iss1/5

How do you select books for your school or classroom library, or to use in lessons? What influences your decisions? In this article, Associate Professor Helen Adam recommends teachers carry out an audit of their collections.

Follow the steps: Take stock of what you currently have. How many books feature disabled characters? How are they portrayed? Where are the gaps? Make a plan to fill those gaps deliberately.