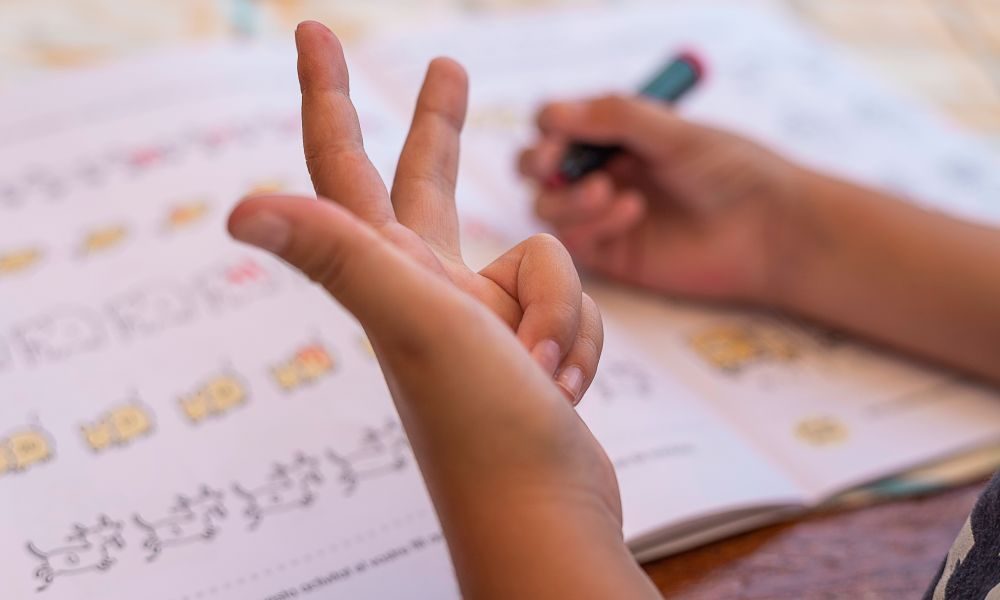

Do your students count on their fingers when completing mathematics tasks? As a teacher, particularly working in the early years or in primary school, do you encourage them to count on their fingers, or do you instead focus on supporting them to make calculations mentally?

New research shows finger counting can have a positive impact on student outcomes – acting as a developmental scaffold toward efficient mental arithmetic – but only when it’s used at a specific age.

Teacher questions prompting the study

Marie Krenger and Professor Catherine Thevenot from the University of Lausanne in Switzerland conducted a longitudinal study following children from the age of 4-and-a-half until they were 7-and-a-half years old to assess the prevalence and impact of finger counting. They found that young children who use their fingers to solve arithmetic problems outperform those who do not, but that this trend reverses in older children around the age of 7.

‘This research was prompted by questions from primary school teachers during in-service training sessions I was leading,’ Professor Thevenot from the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, tells Teacher. ‘They repeatedly asked whether children should be encouraged to use their fingers when solving calculations, or whether, on the contrary, they should be asked to stop and solve problems mentally.

‘At the time, I could not find clear answers to these questions in the scientific literature, which led me to develop my own line of research on the topic almost 10 years ago. I initially thought it would take one or 2 years to provide teachers with evidence-based guidance. Ten years later, I am still working on these questions. That said, we now have a substantial body of results, so the effort has certainly not been in vain.’

What were the research findings?

The researchers published their findings in the journal Developmental Psychology late last year (Krenger & Thevenot, 2025).

The research involved testing 192 children in Switzerland, all of middle- to high-socioeconomic status, at 7 different points over 3 years with an addition task. Specifically, the researchers asked the students to orally solve an addition task presented to them on a card, and they observed how the students solved the task.

Virtually all children were observed using their fingers to help solve the addition task at some point during the study. The results show that up to the age of 5-and-a-half, more children solved addition problems without using their fingers than with them. From this age, until the age of 6-and-a-half, this pattern reversed, with finger users outnumbering non finger users – in fact, the highest proportion of finger users across the testing points was observed at age 6-and-a-half. By the time the children were 7 to 7-and-a-half years old, the number of finger users declined, eventually equalling the number of students not using their fingers.

In terms of the children’s performance, the researchers conclude that, until the very end of the testing period (that is, when children are 7-and-a-half years old), finger users consistently outperform non finger users. In addition, the higher average performance of non finger users compared to finger users after the age of 6-and-a-half was found to be driven by students who formerly used their fingers.

‘Most non finger users by age of 6.5 were in fact ex-finger users,’ the paper reads. ‘Importantly, they presented higher arithmetic performance than finger users and genuine non finger users of the same age. These original findings provide the first empirical evidence that finger counting acts as a developmental scaffold toward efficient mental arithmetic, rather than as a mere useful but limiting strategy eventually hindering development.’

Findings show finger counting supports the development of arithmetic skills

Professor Thevenot tells Teacher she was surprised to find that children who use their fingers to count between the ages of 4 and-a-half to at least 6-and-a-half, are those with the strongest arithmetic skills.

‘They are also the children with the highest cognitive resources: they show better memory capacities and stronger reasoning abilities. This was unexpected, because the common, intuitive view of finger counting is that children who rely on their fingers are lagging behind peers who can already solve calculations mentally. Our results showed exactly the opposite,’ she says.

‘We showed that finger counting is not merely a strategy that is useful at a certain point in development but that would later prevent children from moving on to more elaborated strategies as problems become more complex (for example, when numbers can no longer be easily represented on the fingers because they exceed 5 or 10). In fact, the opposite is true. Children who use their fingers early in their life, between the age of 4- and 5-and-a-half are also those who show the strongest arithmetic abilities at the age of 7 to 7-and-a-half. Finger counting therefore does not trap children in immature strategies. Rather, it most likely supports the transition towards more mature and fully mental ones.’

Teachers can explicitly teach the use of finger counting for younger students

This research also showed that children aged between 4 and 6 who do not spontaneously use their fingers to solve calculation problems, and who therefore perform less well than those who do, can be taught this strategy.

‘We taught them to represent one number on one hand and the other number on the other hand, and then to count all the raised fingers,’ Professor Thevenot tells Teacher. ‘Seventy-five percent of the children were able to adopt this strategy, and they showed a substantial improvement in their calculation performance.

‘The message for teachers is therefore clear. They should not only encourage finger use in children who already rely on it, but also explicitly teach these strategies to children who are experiencing difficulties.’

The use of finger counting is not always advised as students get older

While many of the research findings were positive towards the use of finger counting, an important observation was realised as the children got older. The researchers found a negative correlation between students’ scores in the addition task at the age of 4-and-a-half, and the use of fingers to count at the age of 7-and-a-half. In other words, from around the age of 7, children who have ceased relying on finger counting outperform those who continue to use their fingers (both confirmed and newly finger users).

‘Thus, low performing children in kindergarten are more likely to still rely on finger strategies when their higher performing peers have already shifted to more mature procedures. Intervening as early as possible seems therefore crucial to disrupt persistent learning difficulties,’ the paper reads.

Avenues for further research

Professor Thevenot says they next want to determine whether, when finger counting is taught, children learn more than a simple procedure for solving calculations.

‘We suspect that they may also acquire important principles about numbers and counting. For instance, they may learn that numbers can be represented in different ways – through objects, fingers, or number words – or that, when counting, each word must be associated with one and only one object,’ she tells Teacher.

‘Another key question concerns the 25% of children who do not adopt the strategy even when it is taught and who, unfortunately, continue to show low performance. One possibility is that these children are unable to make sense of the strategy because of a more fundamental difficulty with number comprehension. This is precisely what we aim to investigate in the coming years.’

References

Krenger, M., & Thevenot, C. (2025). The role of children’s finger counting history on their addition skills. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0002099

Reflect on how students in your classroom typically solve addition tasks. Does the use of finger counting align with what was found in this study?

This research showed that children who do not spontaneously use their fingers to solve calculation problems can show improvement in their calculation performance after being explicitly taught by teachers to use their fingers. Is this something you could introduce into your classroom practice this year? How will you monitor the impact?